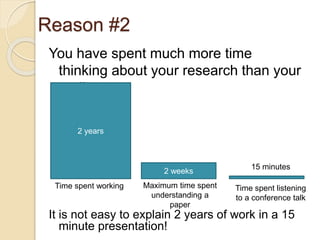

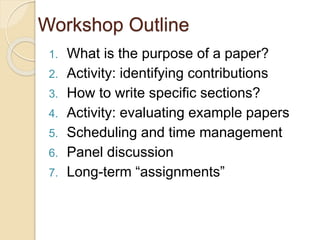

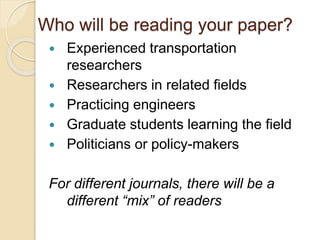

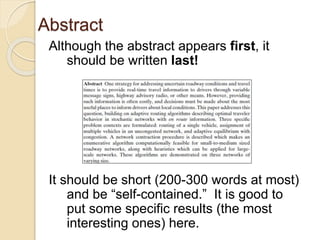

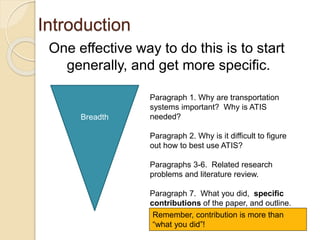

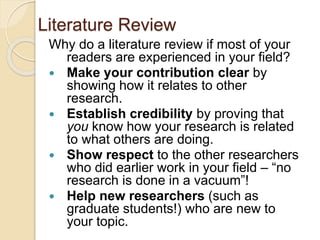

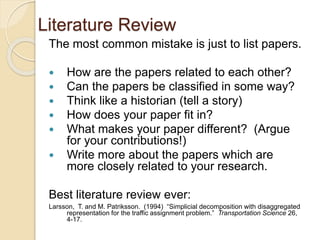

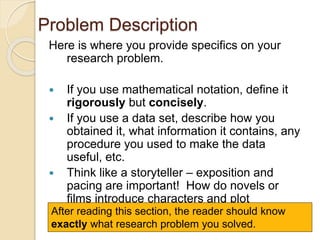

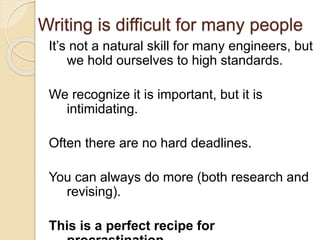

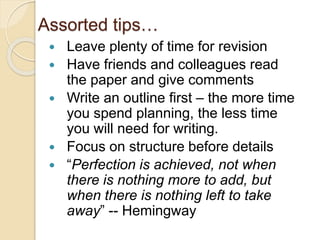

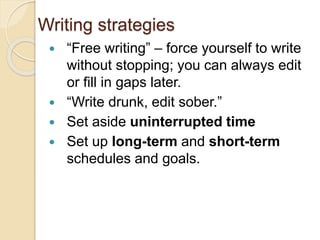

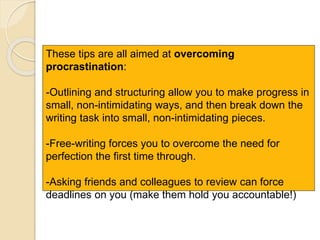

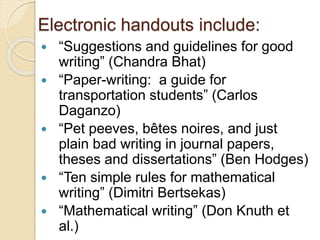

The document emphasizes the importance of effective communication in writing technical papers, detailing how clear writing and presentation can significantly enhance the dissemination of research findings. It covers essential components of a paper, strategies for effective writing, and the significance of literature reviews, while also providing practical activities and writing tips. Overall, the document serves as a comprehensive guide for researchers to improve their writing skills and make meaningful contributions to the field.