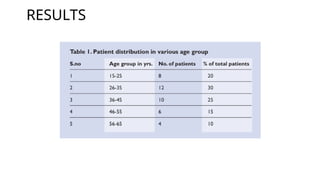

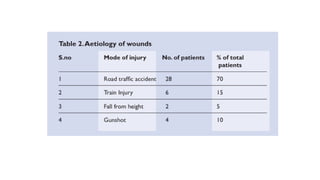

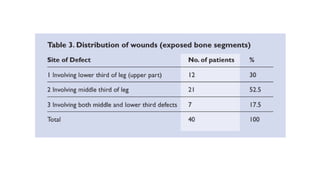

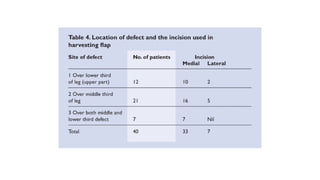

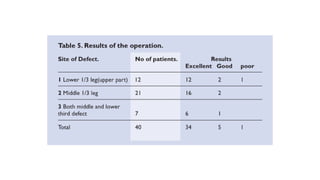

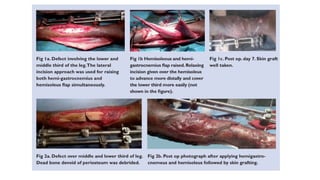

The document discusses the use of the proximally-based hemisoleus muscle flap for reconstructing complex lower limb wounds, particularly following severe trauma. It presents a study of patients aged 15-65 who underwent surgeries using this flap technique, detailing methodologies, surgical techniques, and postoperative care. The findings indicate that the hemisoleus flap proves effective for covering soft tissue defects and can significantly contribute to functional recovery, although complications can arise in severe cases.