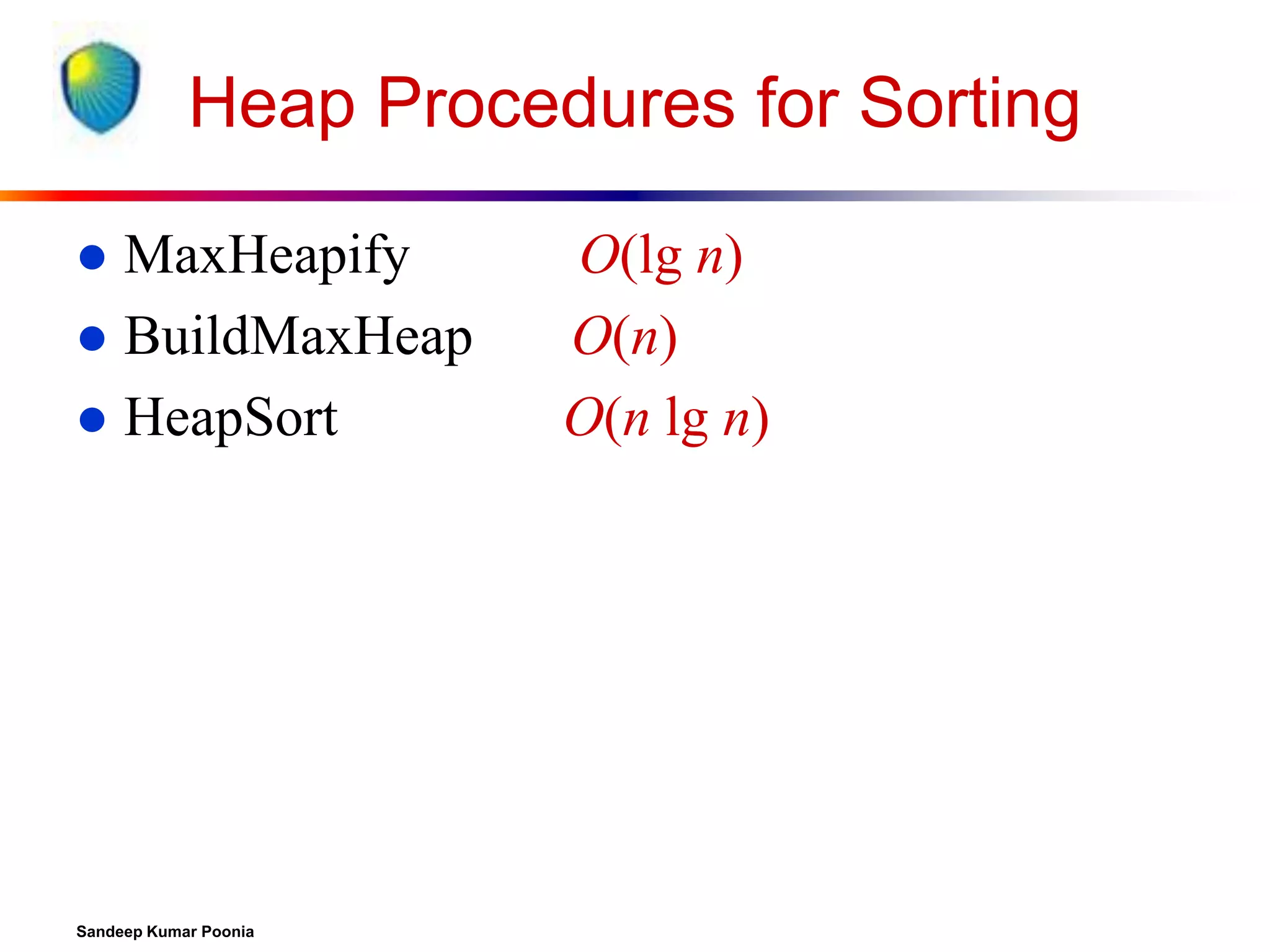

The document discusses algorithms for heap data structures and their applications. It begins with an introduction to heaps and their representation as complete binary trees or arrays. It then covers the heap operations of MaxHeapify, building a max heap, and heapsort. Heapsort runs in O(n log n) time by using a max heap to iteratively find and remove the maximum element. The document concludes by discussing how heaps can be used to implement priority queues, with common operations like insert, extract maximum, and increase key running in O(log n) time.

![Heaps

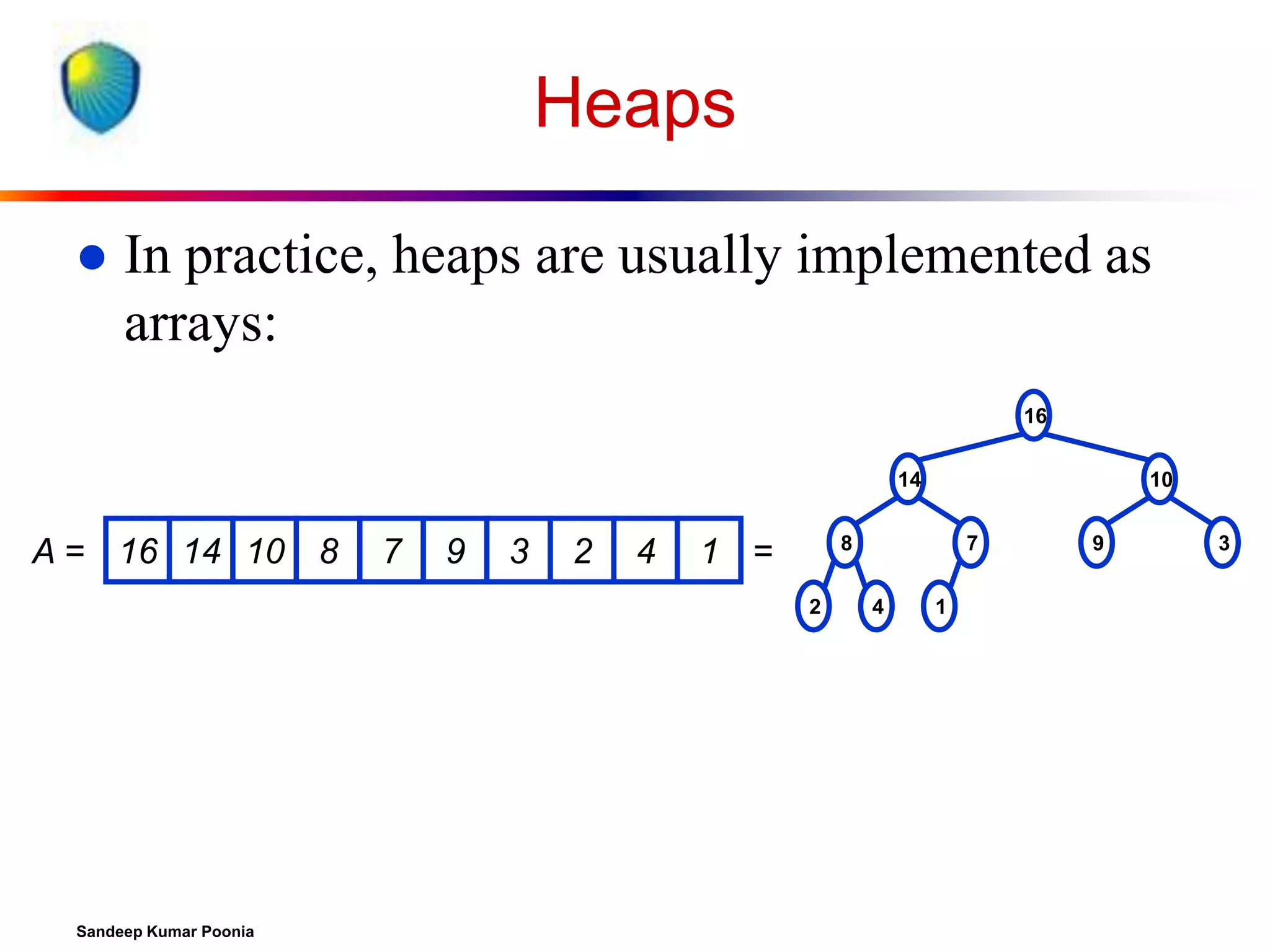

To represent a complete binary tree as an array:

The root node is A[1]

Node i is A[i]

The parent of node i is A[i/2] (note: integer divide)

The left child of node i is A[2i]

The right child of node i is A[2i + 1]

16

14

A = 16 14 10 8

7

9

3

2

4

8

1 =

2

Sandeep Kumar Poonia

10

7

4

1

9

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-8-2048.jpg)

![The Heap Property

Heaps also satisfy the heap property:

A[Parent(i)] A[i]

for all nodes i > 1

In other words, the value of a node is at most the

value of its parent

Where is the largest element in a heap stored?

Definitions:

The height of a node in the tree = the number of

edges on the longest downward path to a leaf

The height of a tree = the height of its root

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-10-2048.jpg)

![Procedure MaxHeapify

MaxHeapify(A, i)

1. l left(i)

2. r right(i)

3. if l heap-size[A] and A[l] > A[i]

4. then largest l

5. else largest i

6. if r heap-size[A] and A[r] > A[largest]

7. then largest r

8. if largest i

9. then exchange A[i] A[largest]

10.

MaxHeapify(A, largest)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia

Assumption:

Left(i) and Right(i)

are max-heaps.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-14-2048.jpg)

![Running Time for MaxHeapify

MaxHeapify(A, i)

1. l left(i)

2. r right(i)

3. if l heap-size[A] and A[l] > A[i]

4. then largest l

5. else largest i

6. if r heap-size[A] and A[r] > A[largest]

7. then largest r

8. if largest i

9. then exchange A[i] A[largest]

10.

MaxHeapify(A, largest)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia

Time to fix node i

and its children =

(1)

PLUS

Time to fix the

subtree rooted at

one of i’s children =

T(size of subree at

largest)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-15-2048.jpg)

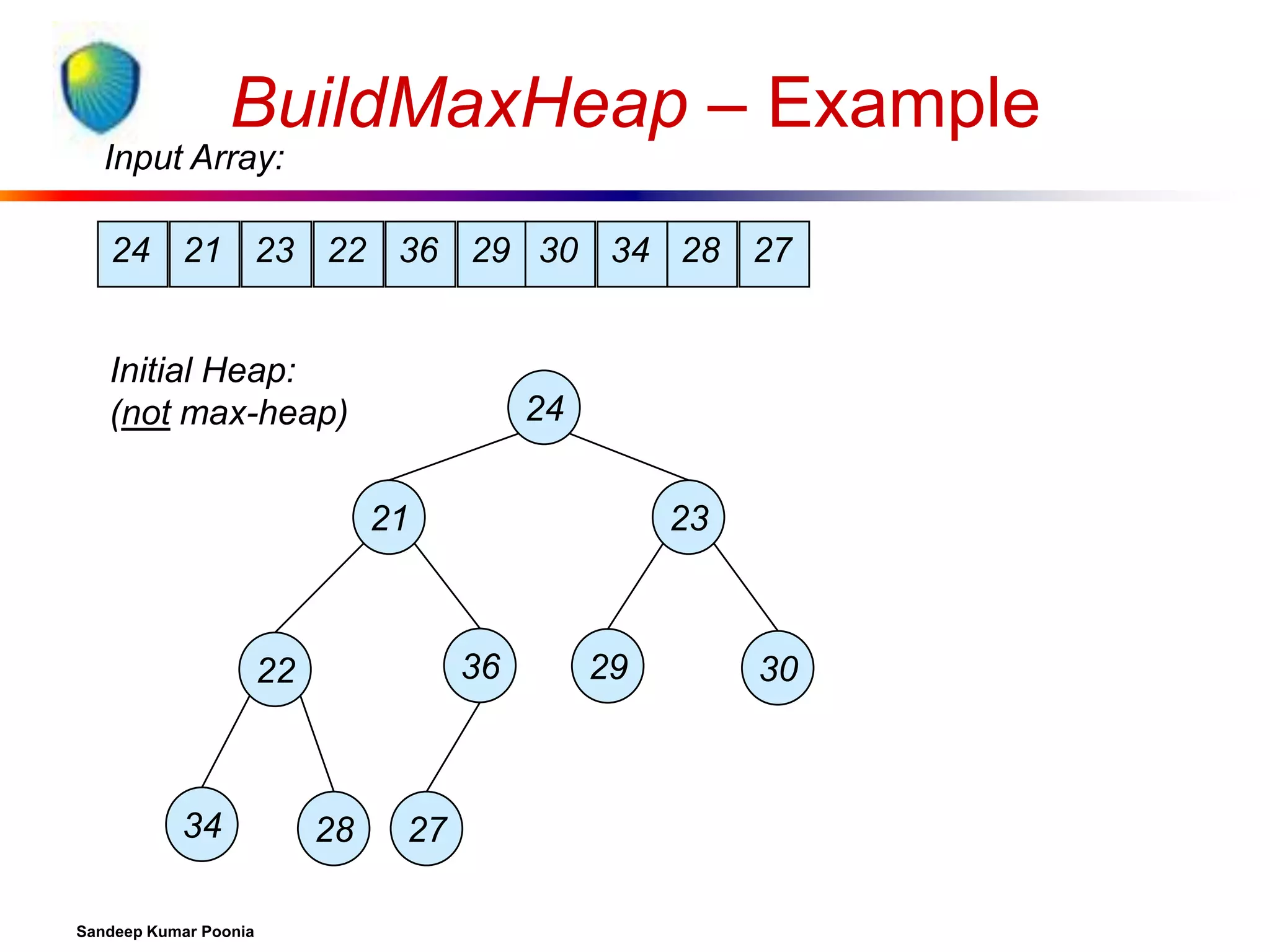

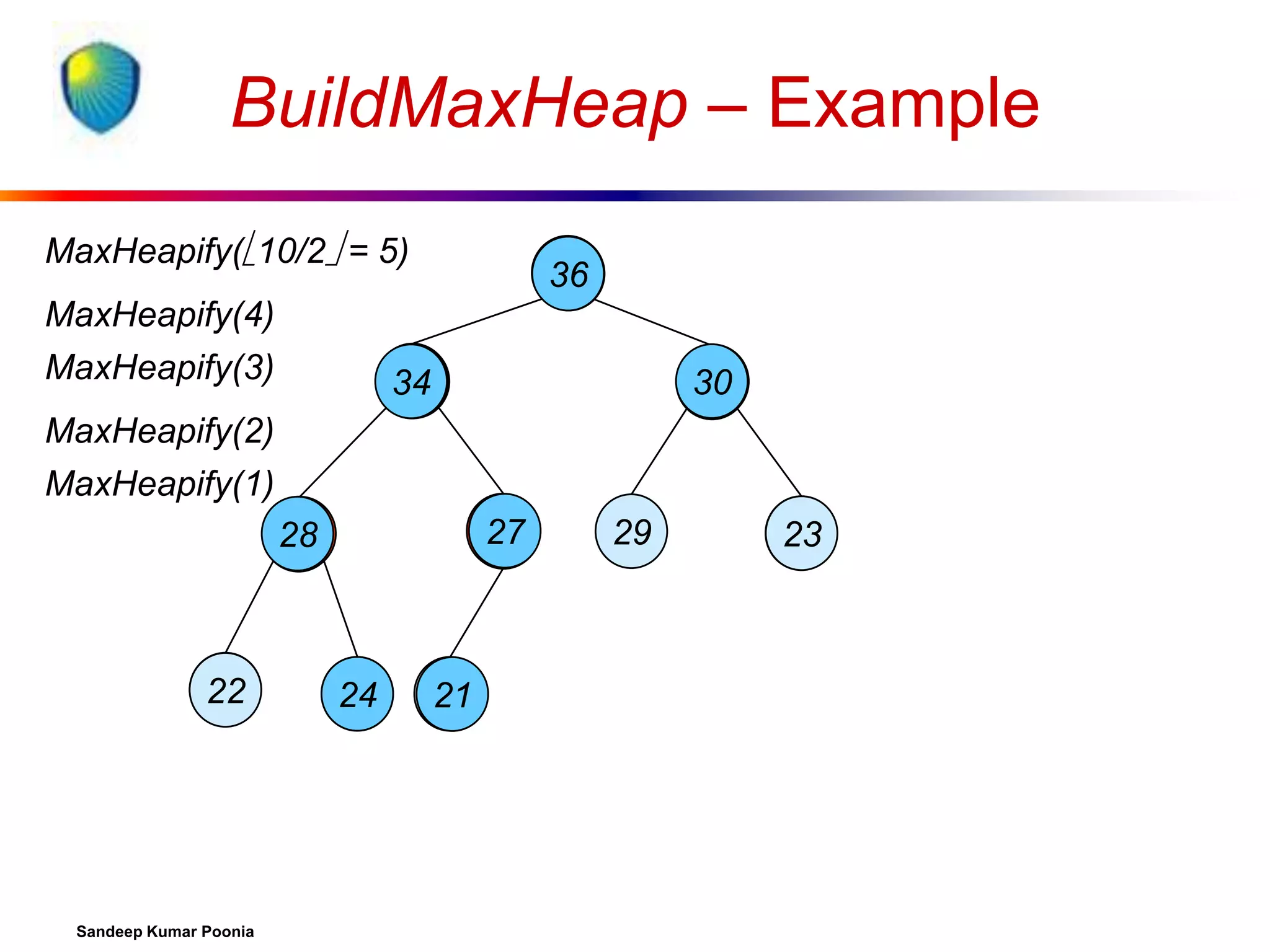

![Building a heap

Use MaxHeapify to convert an array A into a max-heap.

Call MaxHeapify on each element in a bottom-up

manner.

BuildMaxHeap(A)

1. heap-size[A] length[A]

2. for i length[A]/2 downto 1

3.

do MaxHeapify(A, i)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-17-2048.jpg)

![Heapsort

Sort by maintaining the as yet unsorted elements as a

max-heap.

Start by building a max-heap on all elements in A.

Move the maximum element to its correct final

position.

Decrement heap-size[A].

Restore the max-heap property on A[1..n–1].

Exchange A[1] with A[n].

Discard A[n] – it is now sorted.

Maximum element is in the root, A[1].

Call MaxHeapify(A, 1).

Repeat until heap-size[A] is reduced to 2.

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-22-2048.jpg)

![Heapsort(A)

HeapSort(A)

1. Build-Max-Heap(A)

2. for i length[A] downto 2

3.

do exchange A[1] A[i]

4.

heap-size[A] heap-size[A] – 1

5.

MaxHeapify(A, 1)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-23-2048.jpg)

![Algorithm Analysis

HeapSort(A)

1. Build-Max-Heap(A)

2. for i length[A] downto 2

3.

do exchange A[1] A[i]

4.

heap-size[A] heap-size[A] – 1

5.

MaxHeapify(A, 1)

In-place

Not Stable

Build-Max-Heap takes O(n) and each of the n-1 calls

to Max-Heapify takes time O(lg n).

Therefore, T(n) = O(n lg n)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-33-2048.jpg)

![Heap Property (Max and Min)

Max-Heap

For every node excluding the root,

value is at most that of its parent: A[parent[i]] A[i]

Largest element is stored at the root.

In any subtree, no values are larger than the value

stored at subtree root.

Min-Heap

For every node excluding the root,

value is at least that of its parent: A[parent[i]] A[i]

Smallest element is stored at the root.

In any subtree, no values are smaller than the value

stored at subtree root

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-37-2048.jpg)

![Heap-Extract-Max(A)

Implements the Extract-Max operation.

Heap-Extract-Max(A,n)

1. if n < 1

2. then error “heap underflow”

3. max A[1]

4. A[1] A[n]

5. n n - 1

6. MaxHeapify(A, 1)

7. return max

Running time : Dominated by the running time of MaxHeapify

= O(lg n)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-38-2048.jpg)

![Heap-Insert(A, key)

Heap-Insert(A, key)

1. heap-size[A] heap-size[A] + 1

2.

i heap-size[A]

4. while i > 1 and A[Parent(i)] < key

5.

do A[i] A[Parent(i)]

6.

i Parent(i)

7. A[i] key

Running time is O(lg n)

The path traced from the new leaf to the root has

length O(lg n)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-39-2048.jpg)

![Heap-Increase-Key(A, i, key)

Heap-Increase-Key(A, i, key)

1

If key < A[i]

2

then error “new key is smaller than the current key”

3 A[i] key

4

while i > 1 and A[Parent[i]] < A[i]

5

do exchange A[i] A[Parent[i]]

6

i Parent[i]

Heap-Insert(A, key)

1

heap-size[A] heap-size[A] + 1

2 A[heap-size[A]] –

3

Heap-Increase-Key(A, heap-size[A], key)

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-40-2048.jpg)

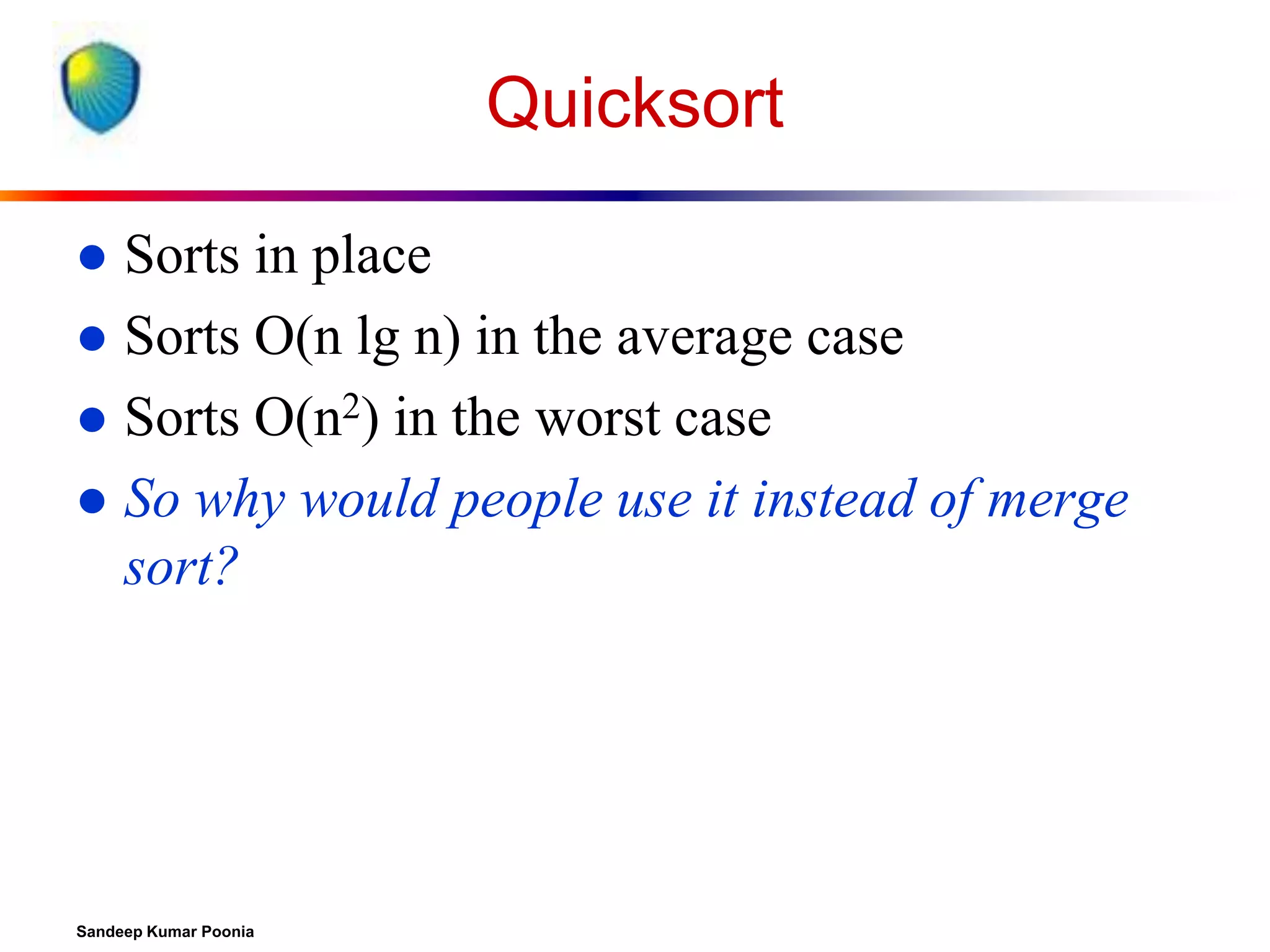

![Quicksort

Another divide-and-conquer algorithm

The array A[p..r] is partitioned into two nonempty subarrays A[p..q] and A[q+1..r]

Invariant:

All elements in A[p..q] are less than all

elements in A[q+1..r]

The subarrays are recursively sorted by calls to

quicksort

Unlike merge sort, no combining step: two

subarrays form an already-sorted array

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-42-2048.jpg)

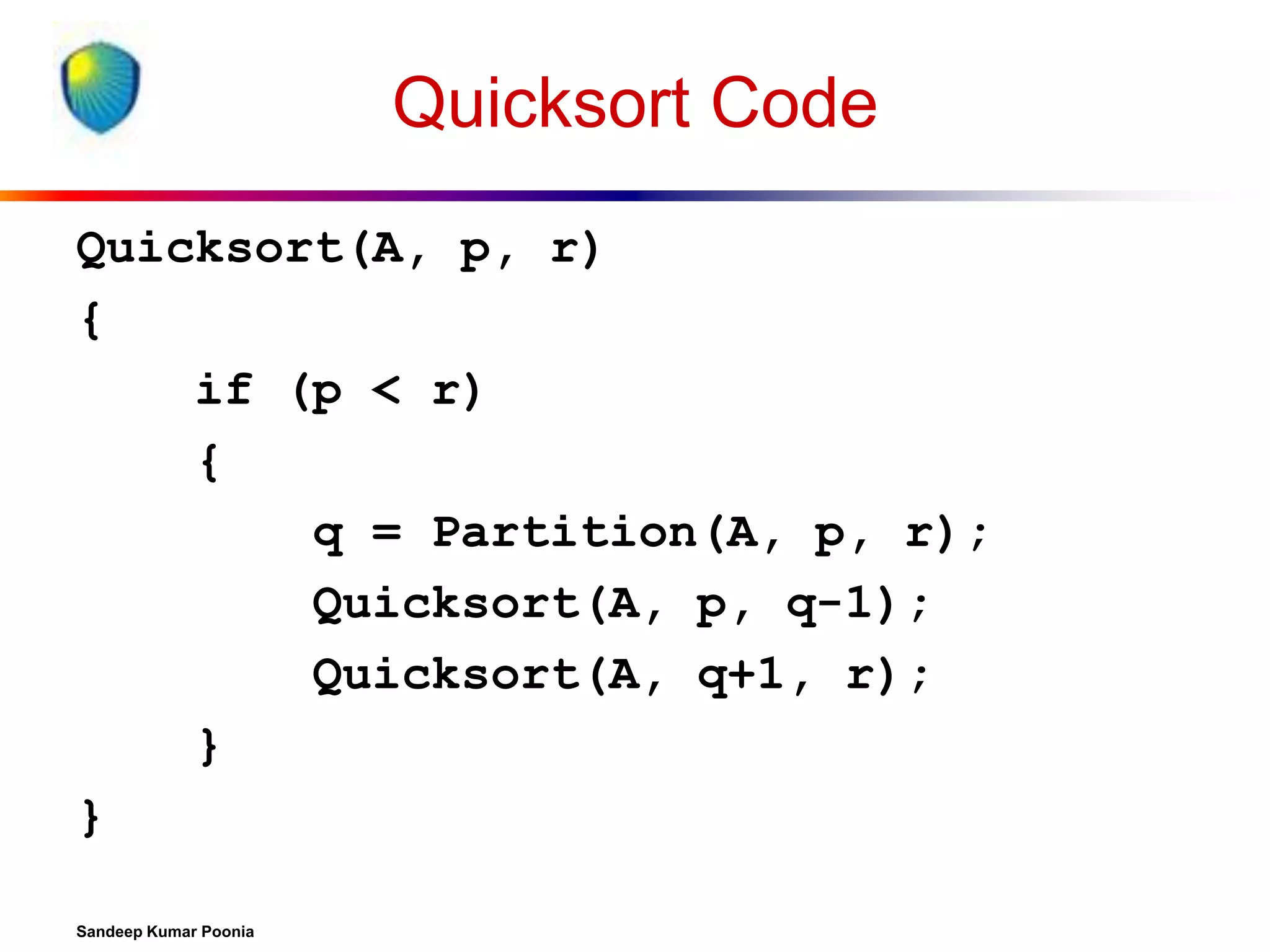

![Partition In Words

Partition(A, p, r):

Select an element to act as the “pivot” (which?)

Grow two regions, A[p..i] and A[j..r]

All

elements in A[p..i] <= pivot

All elements in A[j..r] >= pivot

Increment i until A[i] >= pivot

Decrement j until A[j] <= pivot

Swap A[i] and A[j]

Repeat until i >= j

Return j

Sandeep Kumar Poonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heapsort-quicksort-140217061937-phpapp01/75/Heapsort-quick-sort-45-2048.jpg)