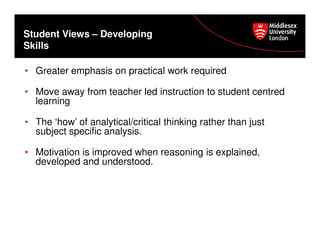

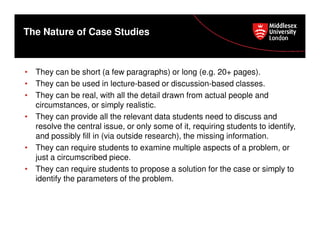

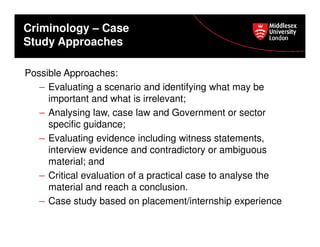

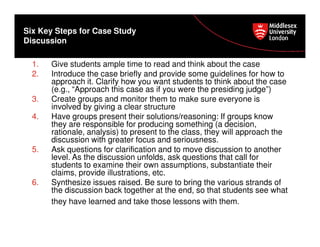

The document outlines the development of a postgraduate course focusing on critical thinking through case studies, highlighting their role in bridging theory and practice. It emphasizes student-centered learning and the necessity of understanding reasoning and fault in arguments. Key elements of effective case studies are discussed along with strategies for facilitating discussions to enhance learning outcomes.