The document provides guidance for developing hazardous materials emergency response plans as required by federal law. It discusses the National Response Team, which coordinates federal planning and response for hazardous spills. It also outlines requirements for emergency planning under various federal acts, and provides guidance on assembling a planning team, conducting hazard and risk analyses, assessing response capabilities, and developing plan elements. The guidance is intended to help state and local governments create effective hazardous materials emergency plans.

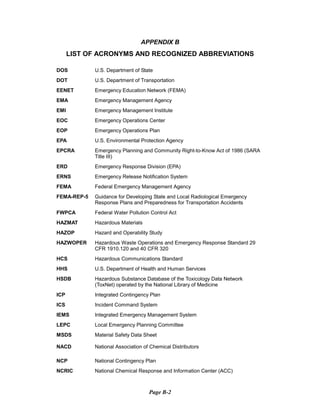

![plan properly addressed by SARA Title III plans

may be substituted into the employer’s

emergency response plan required under

paragraph (q)(2). Employers may also meet

HAZWOPER’s emergency response plan

provisions by following the NRT’s Integrated

Contingency Plan guidance, which can be found

at

http://www.nrt.org/nrt/home.nsf/ba1c0a48225833

4785256449000567e2/205d72330679296885256

46c00742664?OpenDocument. One important

requirement in the standard is to use a site-

specific ICS to coordinate and control the

communication between all site emergency

responders during an emergency involving

hazardous substances.

Employers involved in clean-up of uncontrolled

hazardous waste sites, remediation of RCRA

corrective actions, and operation of hazardous

waste treatment, storage, and disposal (TSD)

facilities must also have an emergency response

plan with similar elements, in accordance with

1910.120(l)(2) or 1910.120(p)(ii). (See 29 CFR

Part 1910.120 [Appendix C of the rule provides

specific guidance for compliance] or visit the

OSHA web site at www.osha.gov.)

A key provision of OSHA’s emergency planning

provisions under HAZWOPER is that employers

have to coordinate their emergency response

plans with outside parties such as LEPCs and

local response organizations.

H. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990

The Clean Water Act (a.k.a. CWA, the Federal

Water Pollution Control Act, and FWPCA)

provides the basis for the NRS. Key planning

requirements are embodied in this statute, which

has been amended several times by various

public laws, including in 1990, by OPA. OPA was

enacted to strengthen the national response

system. It provides for better coordination of spill

contingency planning among Federal, state, and

local authorities. Some of the requirements that

stem from this Act are: the NCP; ACPs;

Response Plans for tank vessels, offshore

facilities and certain onshore facilities; emergency

response

drills; inspection of response equipment; and

EPA's listing of hazardous substances other than

oil.

Area Committees and Area Contingency Plans:

The OPA amendment to the CWA established,

among other things, new planning entities and

requirements for the NRS to deal specifically with

oil spills and CWA hazardous substances during

preparedness and response. The Area

Committee is one such entity, and ACPs are

planning requirements initiated by OPA. These

committees and plans are designed to improve

coordination among the national, regional, and

local planning levels and to enhance the

availability of trained personnel, necessary

equipment, and scientific support that may be

needed to adequately address all discharges. In

the inland zone, where there are region-wide

ACPs, subarea plans provide the detailed

information required by the NCP.

EPA has provided for LEPCs and SERCs to have

input into this area contingency planning process.

The LEPC's primary responsibility is to develop

an emergency response plan for potential

chemical accidents. SERCs are responsible for

supervising and coordinating the activities of the

LEPCs and for reviewing local emergency

response plans for chemical accidents. Thus, the

LEPCs and SERCs' expertise in planning for

response to chemical releases (including

releases of hazardous substances) allows the

Area Committees to effectively address

hazardous substance planning issues, as

necessary.

Under OPA, Area Committees also are charged

with the responsibility to work with state and local

officials to enhance contingency planning and to

assure early planning for joint response efforts.

Among the things Area Committee assistance

should include are appropriate procedures for the

following: mechanical recovery; dispersal;

shoreline clean-up; protecting sensitive

environmental areas; protecting, rescuing, and

rehabilitating fisheries and wildlife.

Area Committees also should help state and local

planners to expedite decisions for the use of

dispersants and other mitigating substances and

devices. Under the approval scheme presented

in the NCP, the Area Committee serves as an

advocate for the dispersant use plan, while the

RRT decides whether the plan is adequate and

may address region-wide or cross-regional

issues. This provides a necessary forum for

dispersant use review.

There is a slightly different procedure for spill

situations that are not addressed by the

pre-authorization plans. In this case, the OSC

Page 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hazardousmaterialsemergency-200908222743/85/Hazardous-materials-emergency-18-320.jpg)

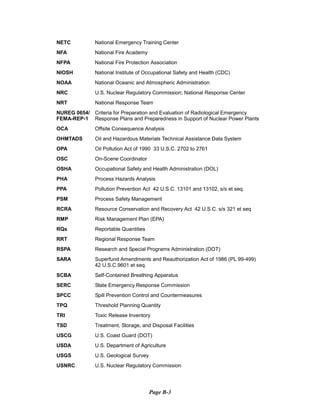

![9 Have locations of materials most likely to be used in mitigating the effects of a

release (e.g., foam, sand, lime) been identified in the plan?

9 Does the plan address the potential needs for evacuation, what agency is

authorized to order or recommend an evacuation, how it will be carried out, and

where people will be moved?

9 Has an emergency operating center, command center, or other central location

with the necessary communications capabilities been identified in the plan for

coordination of emergency response activities?

9 Are there follow-up response activities scheduled in the plan?

9 Are there procedures for updating the plan?

9 Are there addenda provided with the plan, such as laws and ordinances, statutory

responsibilities, evacuation plans, community relations plan, health plan, and

resource inventories (personnel, equipment, maps [not restricted to road maps],

and mutual aid agreements)?

9 Does the plan address the probable simultaneous occurrence of different types of

emergencies (e.g., power outage and hazardous materials releases) and the

presence of multiple hazards (e.g., flammable and corrosive) during hazardous

materials emergencies?

Page D-11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hazardousmaterialsemergency-200908222743/85/Hazardous-materials-emergency-111-320.jpg)

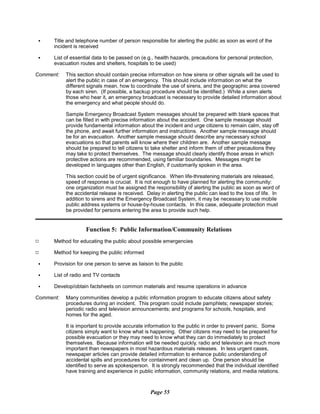

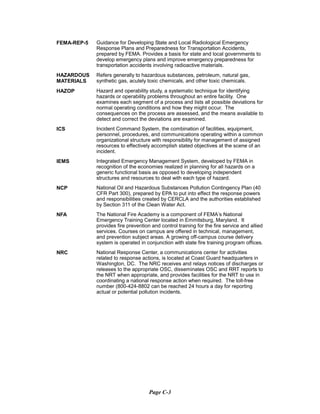

![APPENDIX F

HOTLINE NUMBERS AND

FEDERAL AGENCY WEBSITE ADDRESSES

Listed below are the main website addresses for Federal agencies. These websites

contain contact information for regional offices. If you do not have access to the Internet,

visit your local library to get online. Local phone books will contain contact information for

state offices.

To report a spill call the 24-hour National Response Center Hotline: 1-800-424-8802

www.nrc.uscg.mil/

Federal Emergency Management Agency: www.fema.gov

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: www.epa.gov/ceppo (EPA maintains the RCRA,

Superfund & EPCRA Hotline to answer questions at 1-800-424-9346 [local Washington,

DC area calls: 703-412-9810].)

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: www.atsdr.cdc.gov/

U.S. Department of Energy: www.doe.gov

Department of Agriculture: www.usda.gov

Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration: www.osha.gov

U.S. Coast Guard (G-MER), Marine Safety and Environmental Protection:

www.uscg.mil/hq/g-m/gmhome.htm

U.S. Dept. of Transportation, Research and Special Programs Administration, Office of

Hazardous Materials Safety HazMat Info Line 1-800-467-4922 and website

http:hazmat.dot.govhazmat.dot.gov/

Department of Justice, Environment and Natural Resources Division:

www.usdoj.gov/enrd/enrd-home.html

Department of the Interior: www.doi.gov

Department of Commerce, NOAA: www.noaa.gov

Department of State: www.state.gov

Department of Defense: www.defenselink.mil

Nuclear Regulatory Commission: www.nrc.gov

Page F-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hazardousmaterialsemergency-200908222743/85/Hazardous-materials-emergency-114-320.jpg)