This document provides an overview of health, safety, security and environment (HSSE) implementation during the construction, commissioning and start-up phases of the Pearl GTL project. It discusses several key aspects of HSSE including developing a safety culture, implementing an HSSE management system, establishing an HSSE organization and roles, and identifying critical HSSE processes. The document is intended to share lessons learned from Pearl GTL to help other projects improve their HSSE performance during project transitions from construction to operations.

![51

HSSE in Transition through Project Phases

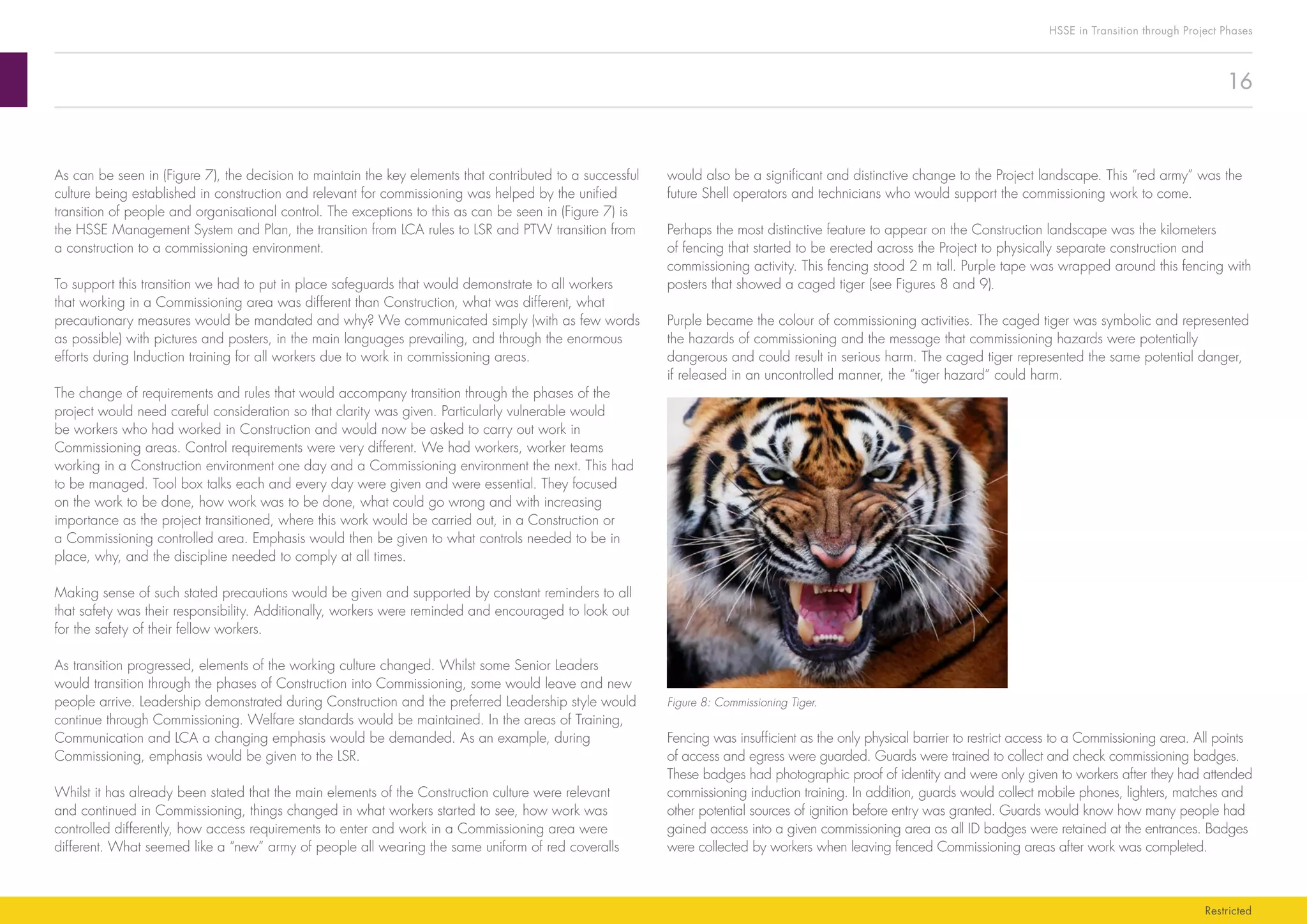

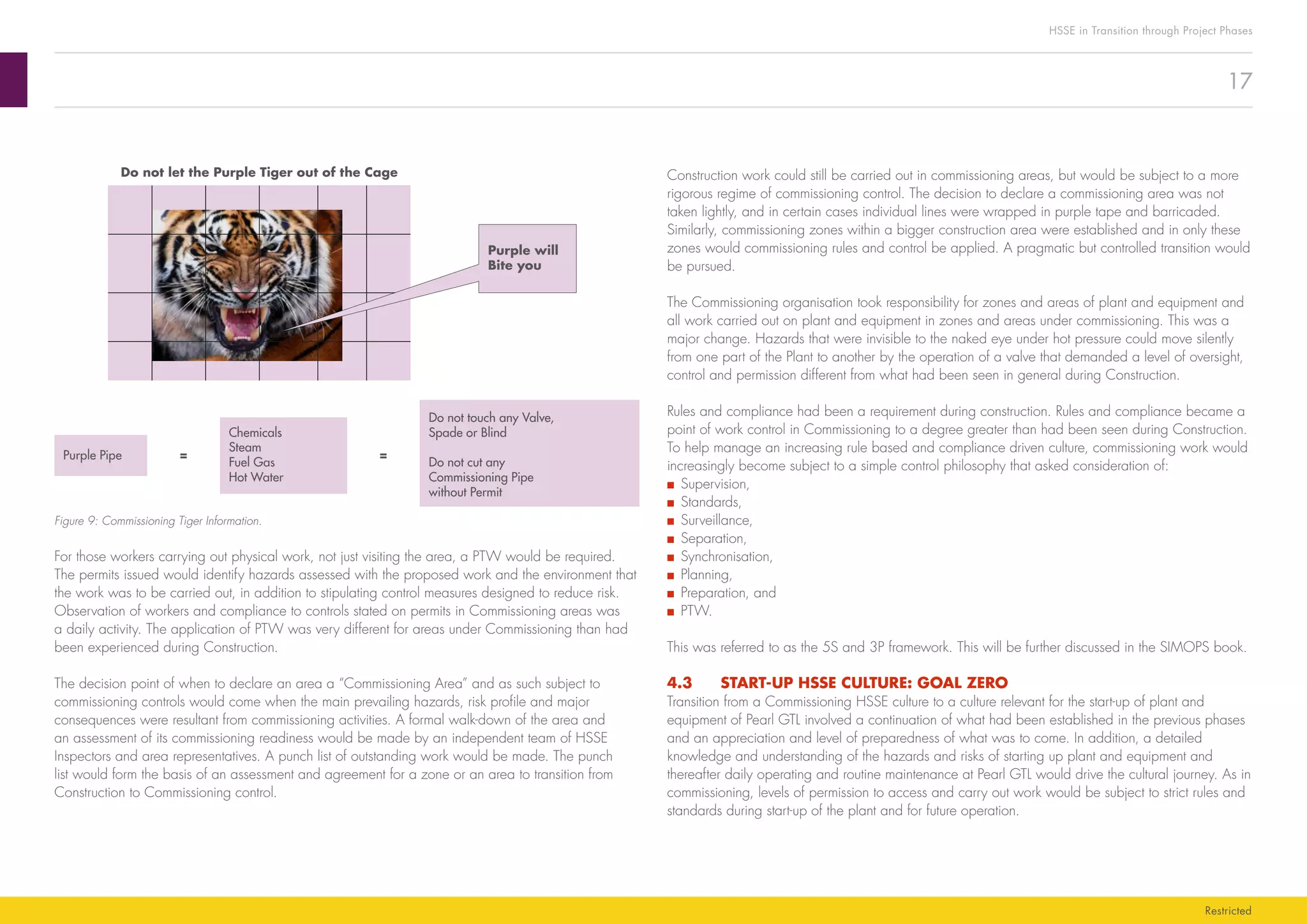

Restricted

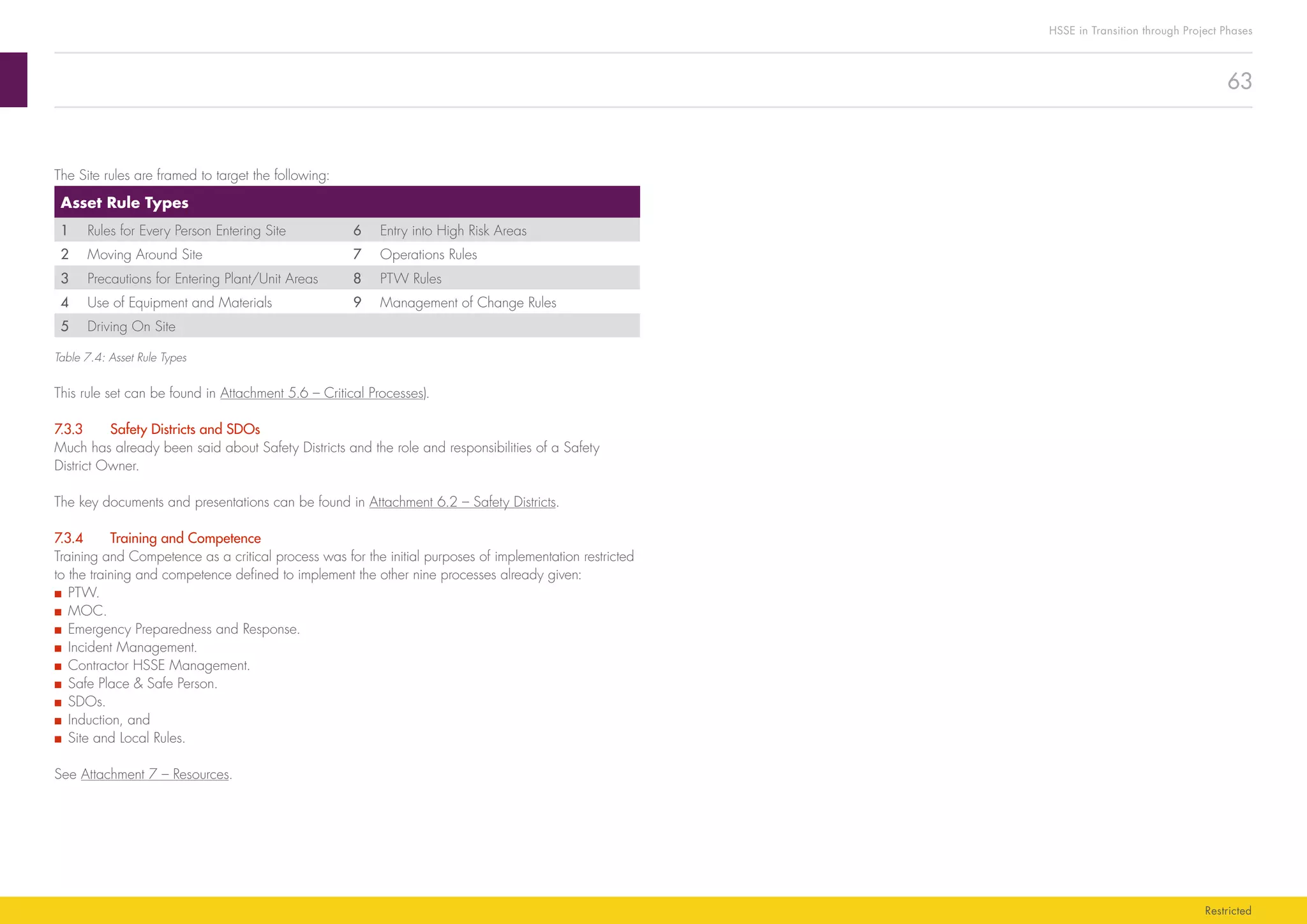

Initiation/Change Reconition

Concept

Approval

Shelved and

terminated

UM Approval

(implementation)

Record in Unit register

Basis of Design (BOD)

And Technical Development

Management Review and Approval

20K$

UM Approval

(Dvelopment BDEP)

BDEP

Shelved and

terminated

Shelved and

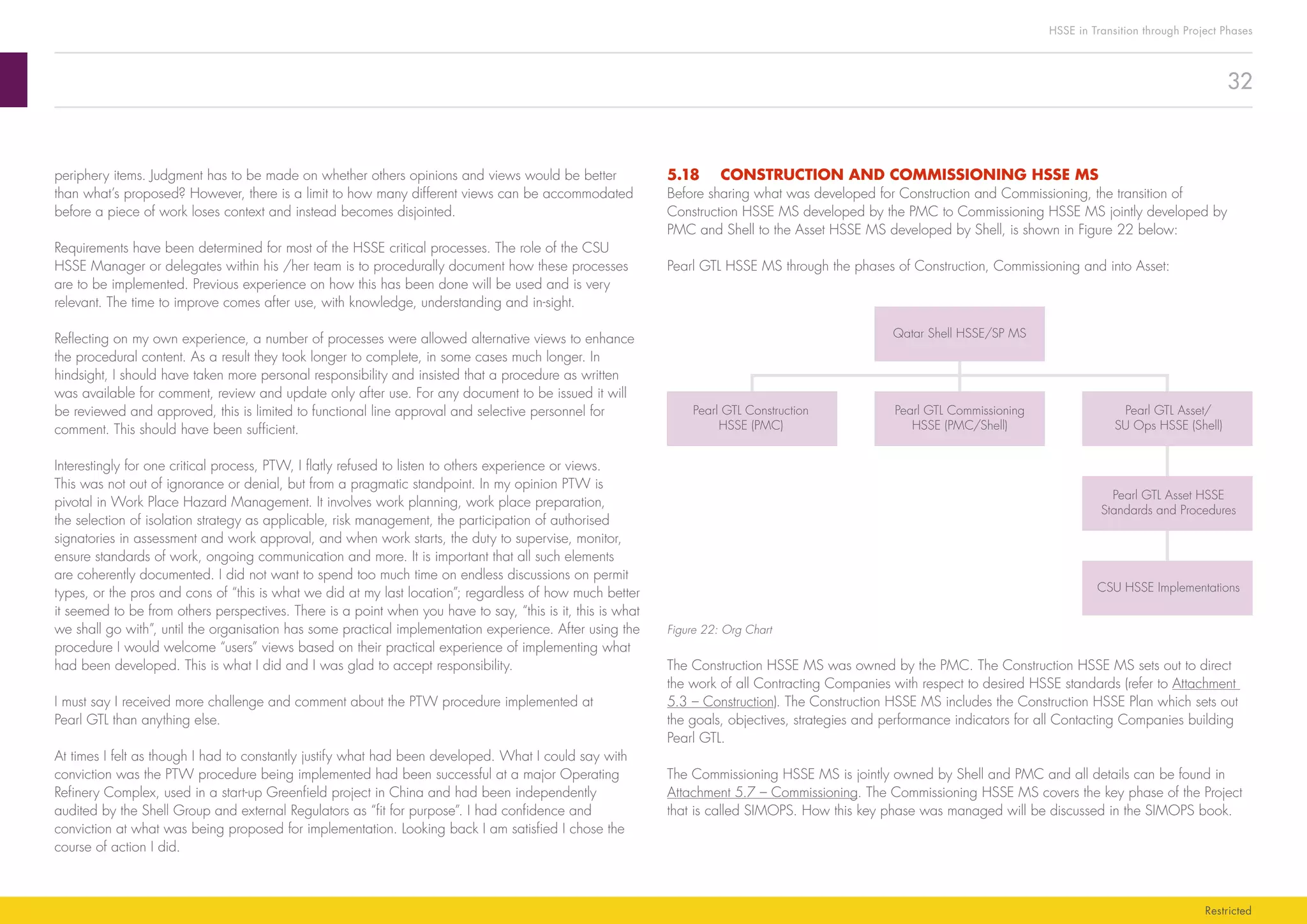

terminated

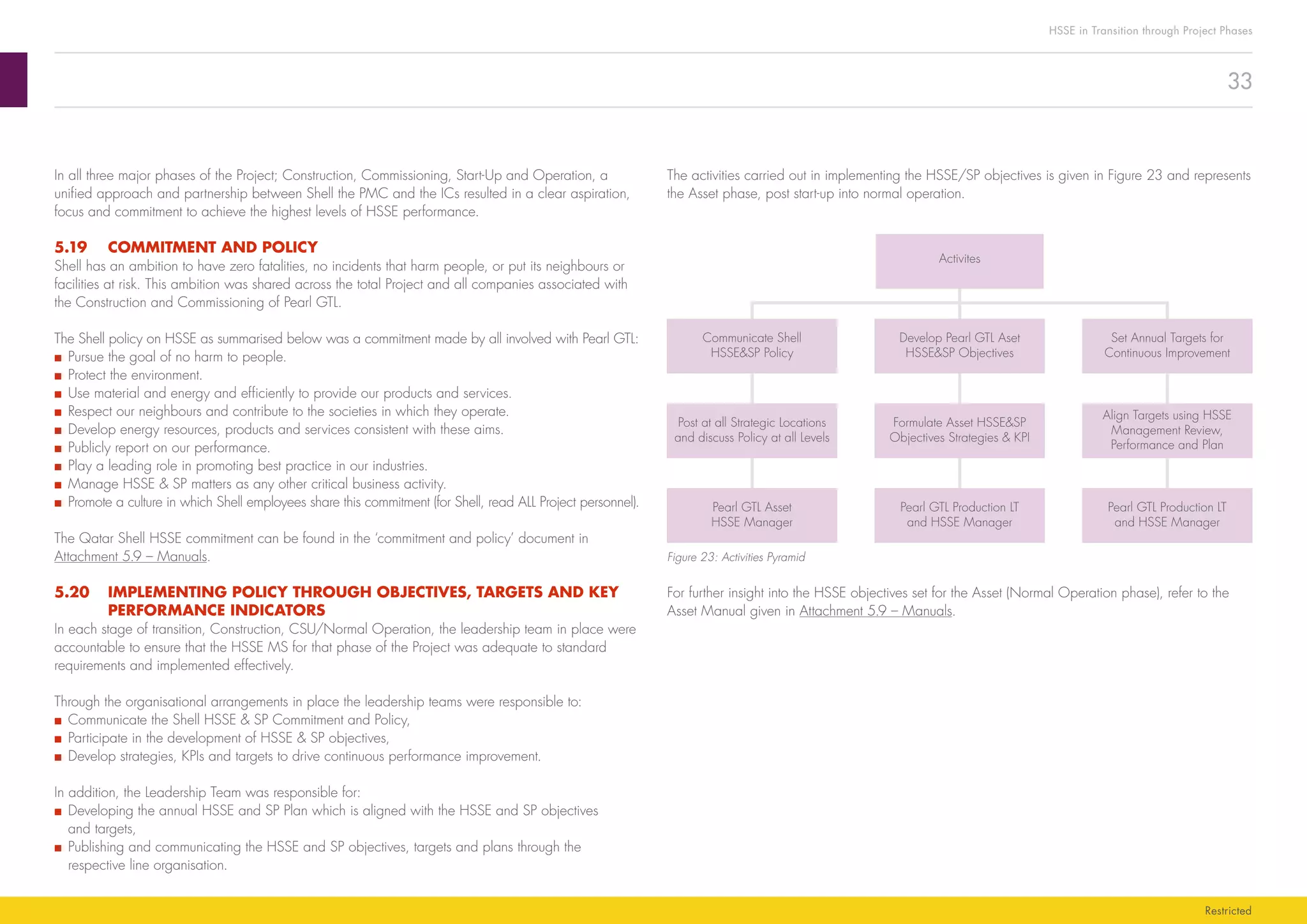

Installation/Execution

(Field) Rediness Review

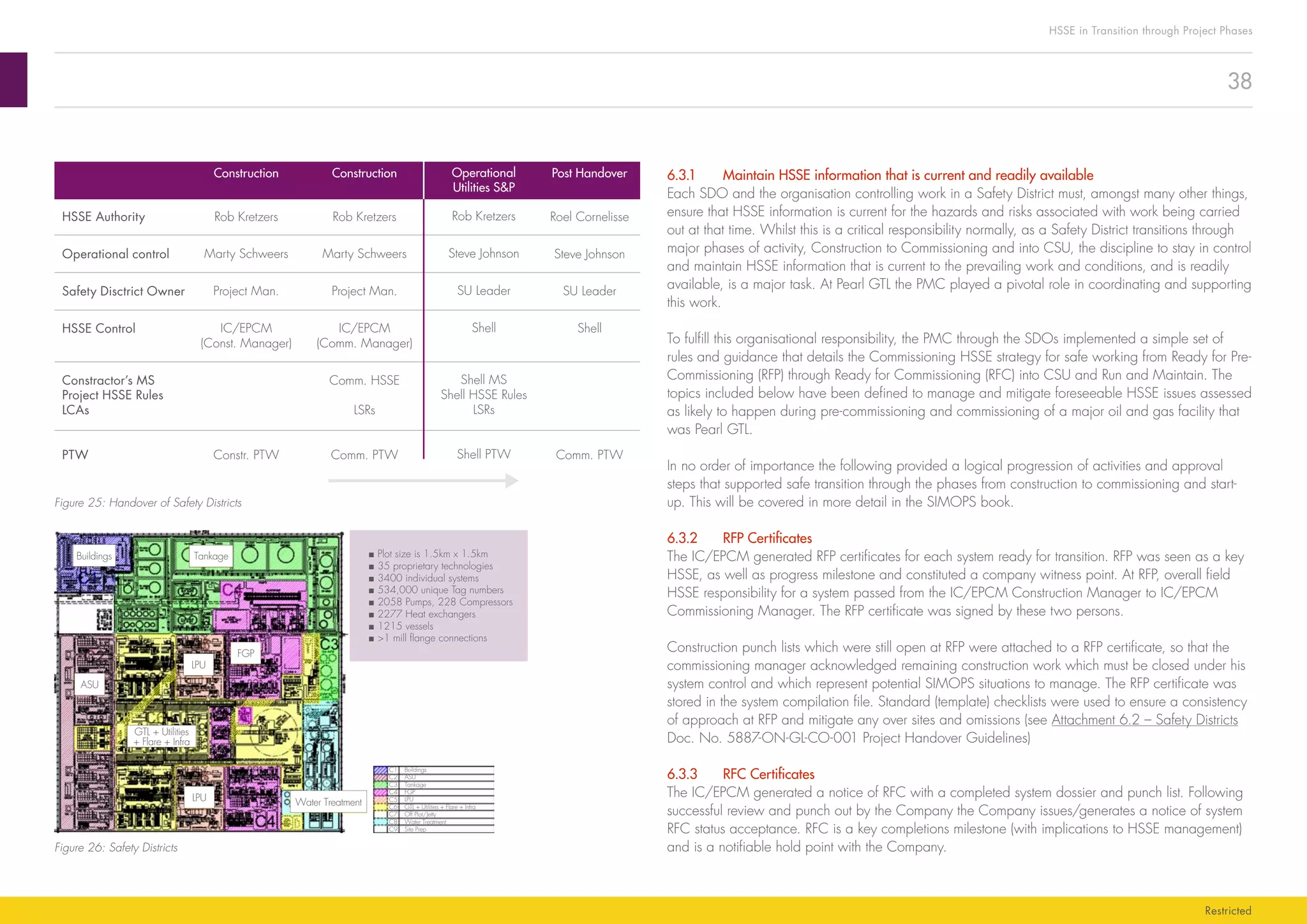

Records Update and Closure

■ Initiator supported by Process engineer (Purpose, priotisation and

50% cost estimate

■ Area Asset Manager

■ Process Engineer requests/confirms register number

■ Process Engineer leads BOD

■ Authorised Technologist/Mechanical Engineer,

Authorised Instrument Engineer defines requirements

for specialist approval

■ Technical specialist sign [Process Safety and Inspection: mandatory

■ Authorised Technologist, Nominated Engineer, Authorised Instrum

Engineer sign

■ Area Asset Mgr

■ Project Engineer supported by Process Engineer [BDEP, 10% cost]

■ Contract board

■ Engineering Mgr and/or Project Engineer and Contractors

■ Process Engineer provides “Work Copy” PEFS to Plant Operation

■ Authorised Mechanical Engineer/Technologist/Instrument Eng.

■ Plant Operations Nominee

■ Plant technologist provides

■ Led by Project Engineer, or Process Engineer

■ Copy of MOC is filed by Project Engineer

■ Maste copy of MOC is kept by Plant Technologist with red marked

“As Built Copy”

Engineering

Required

Section of MOC Process Roles

A1-A4

C-D

A5

E

B

N

N

N

N

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

N

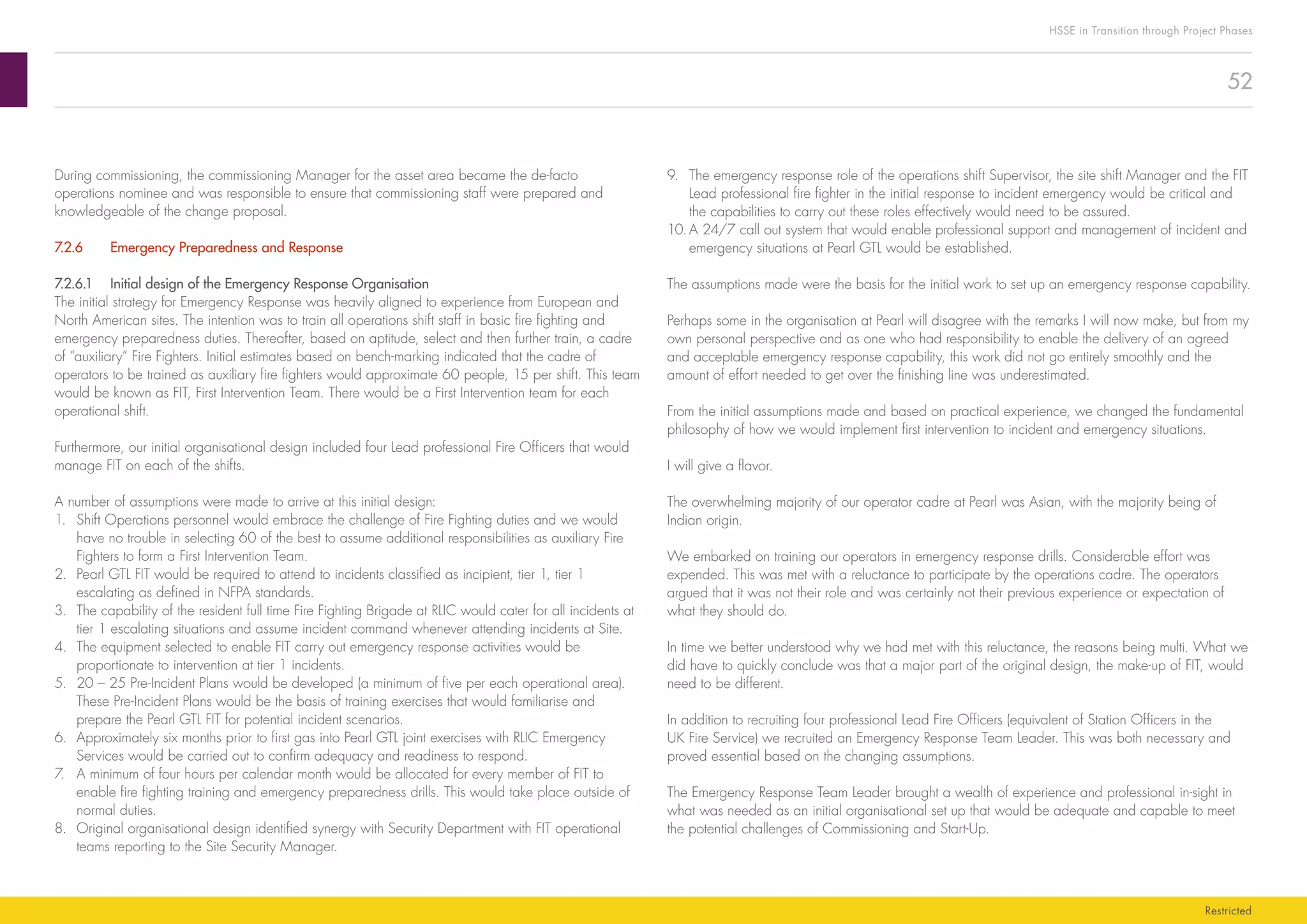

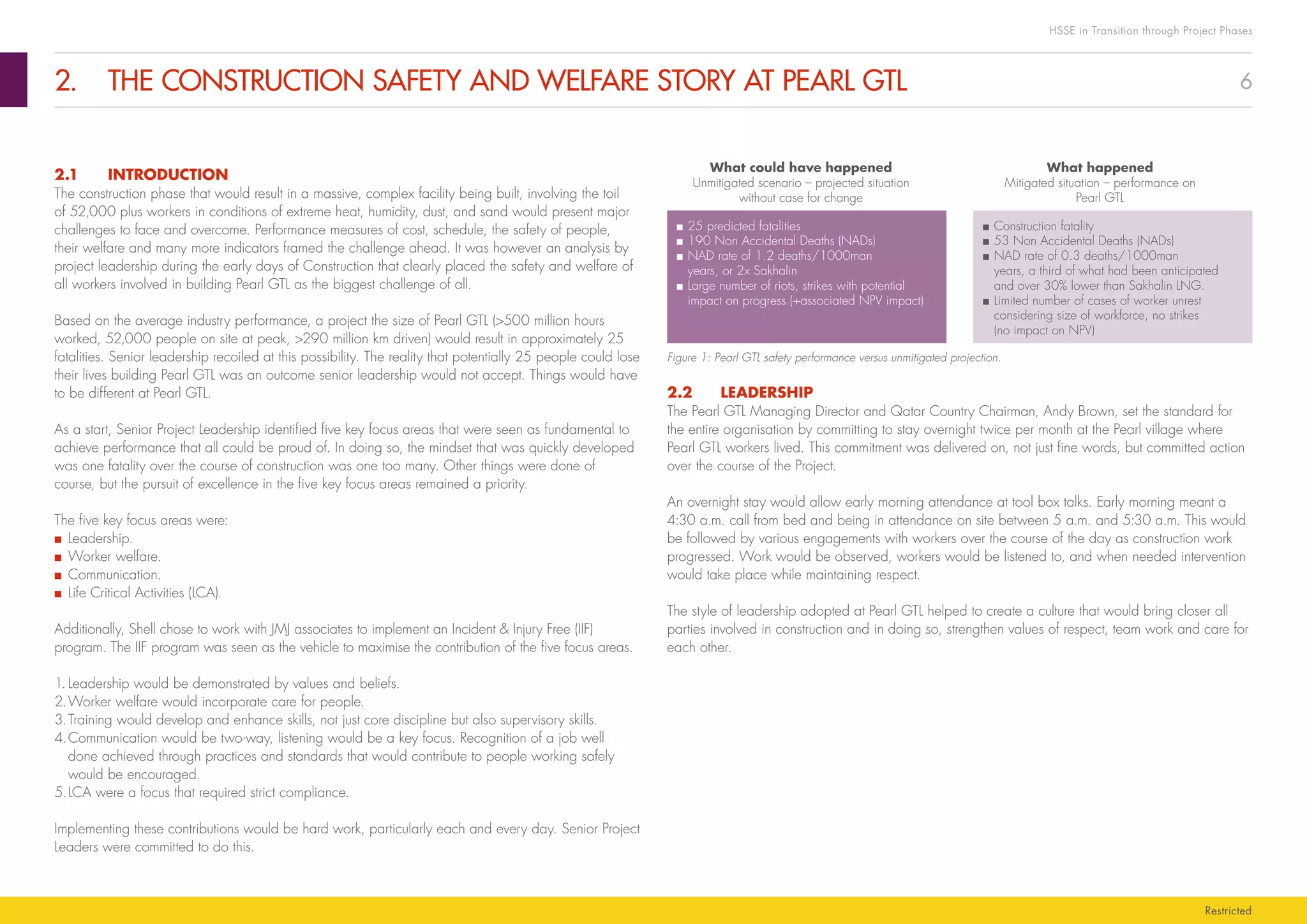

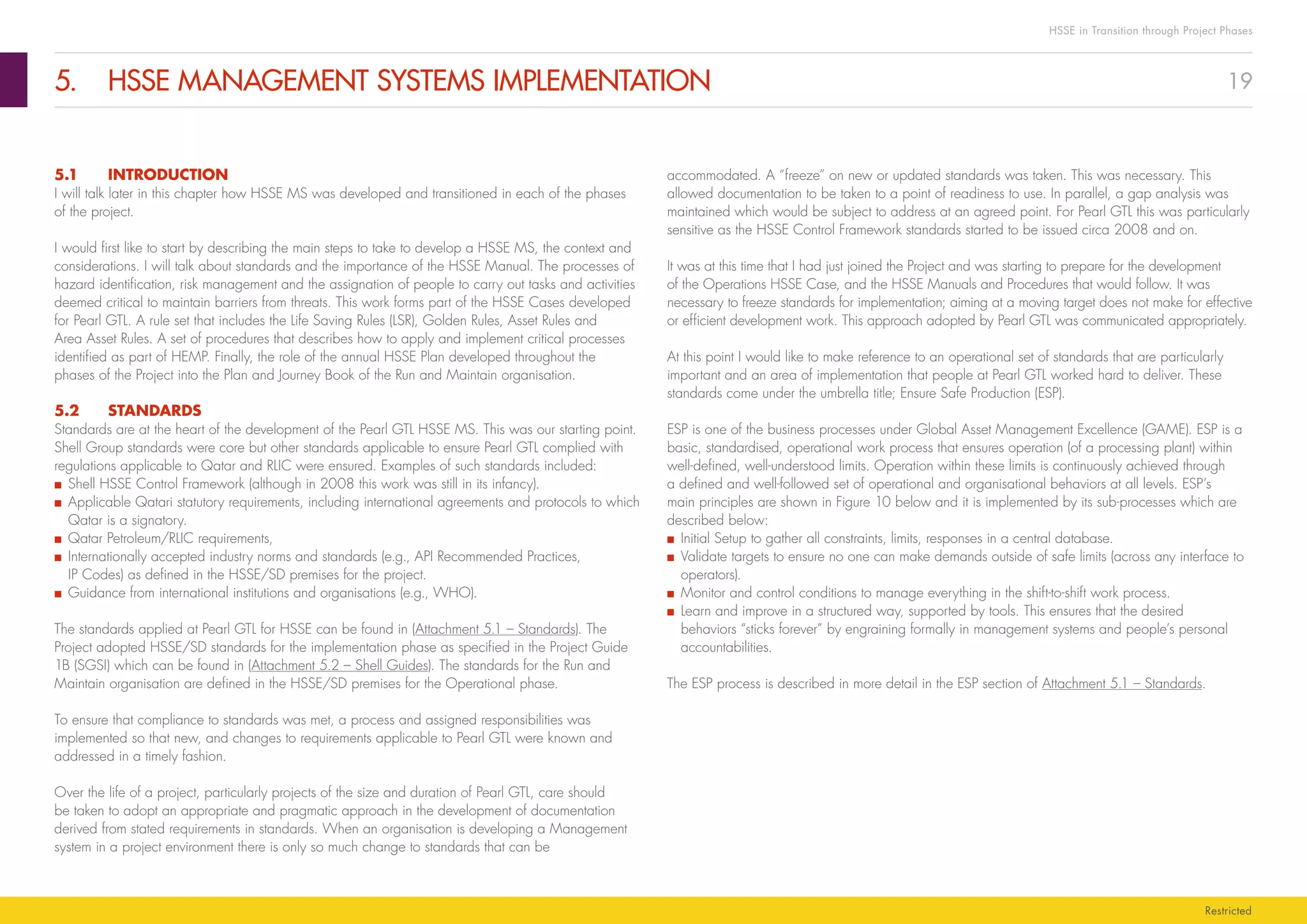

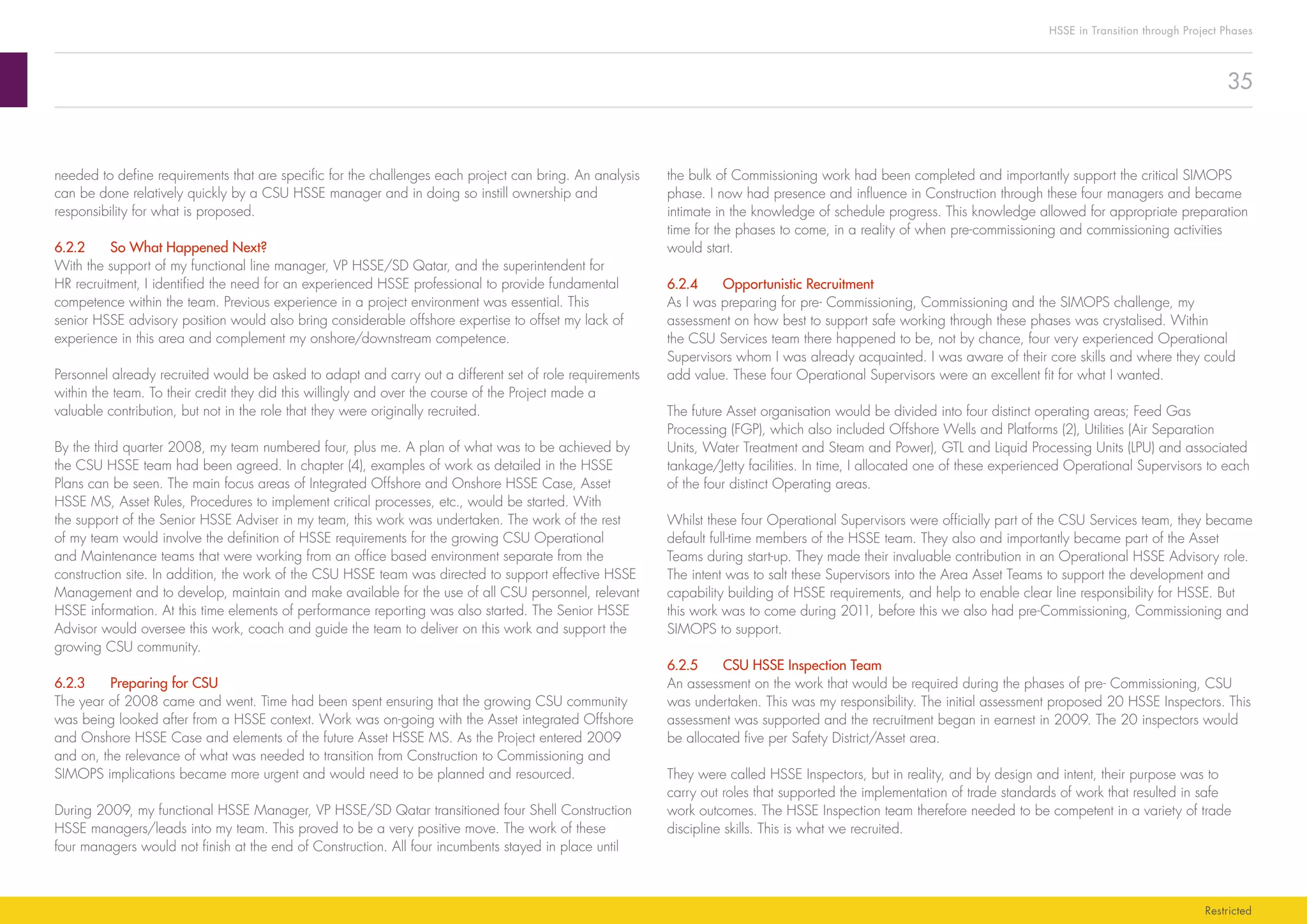

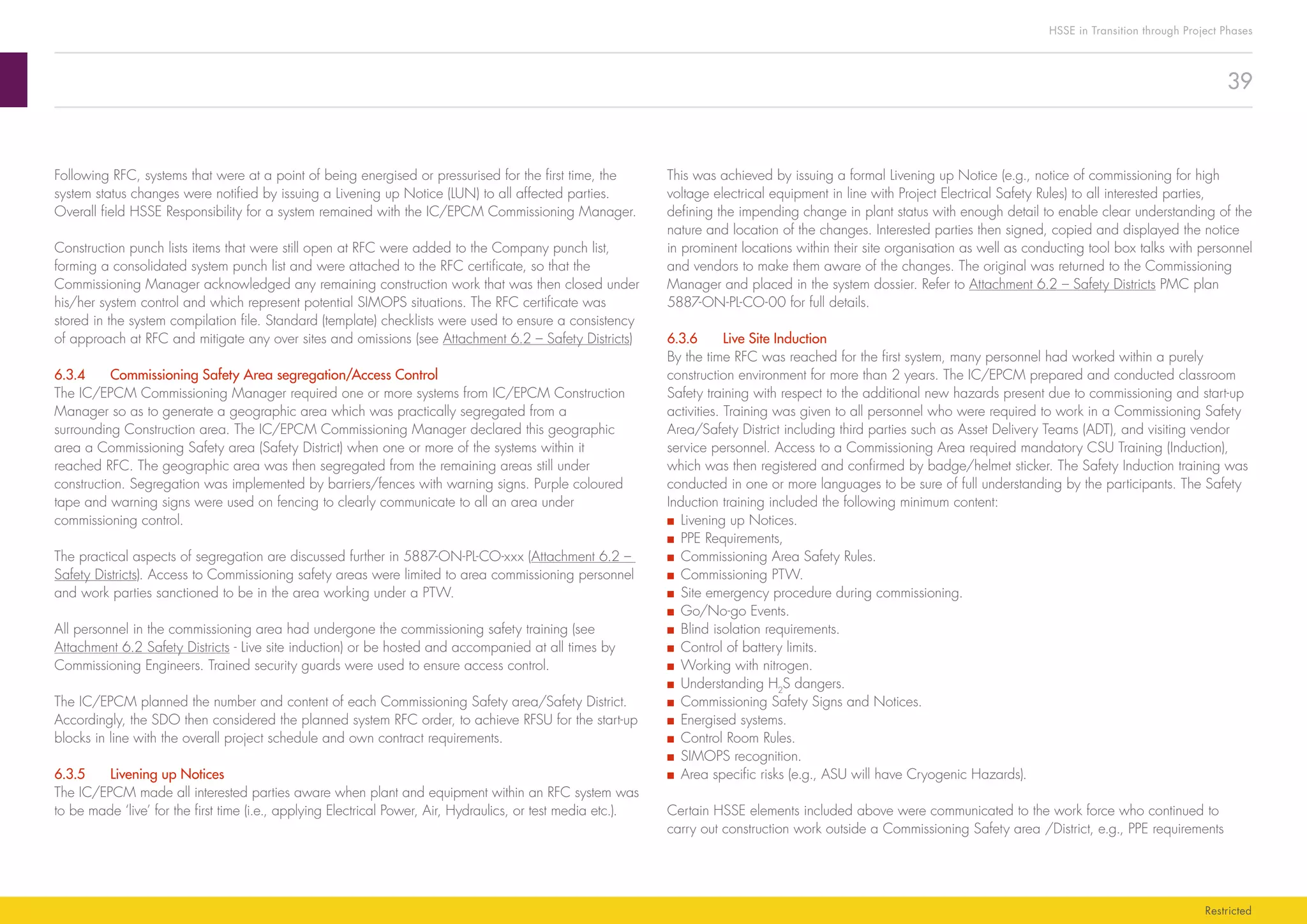

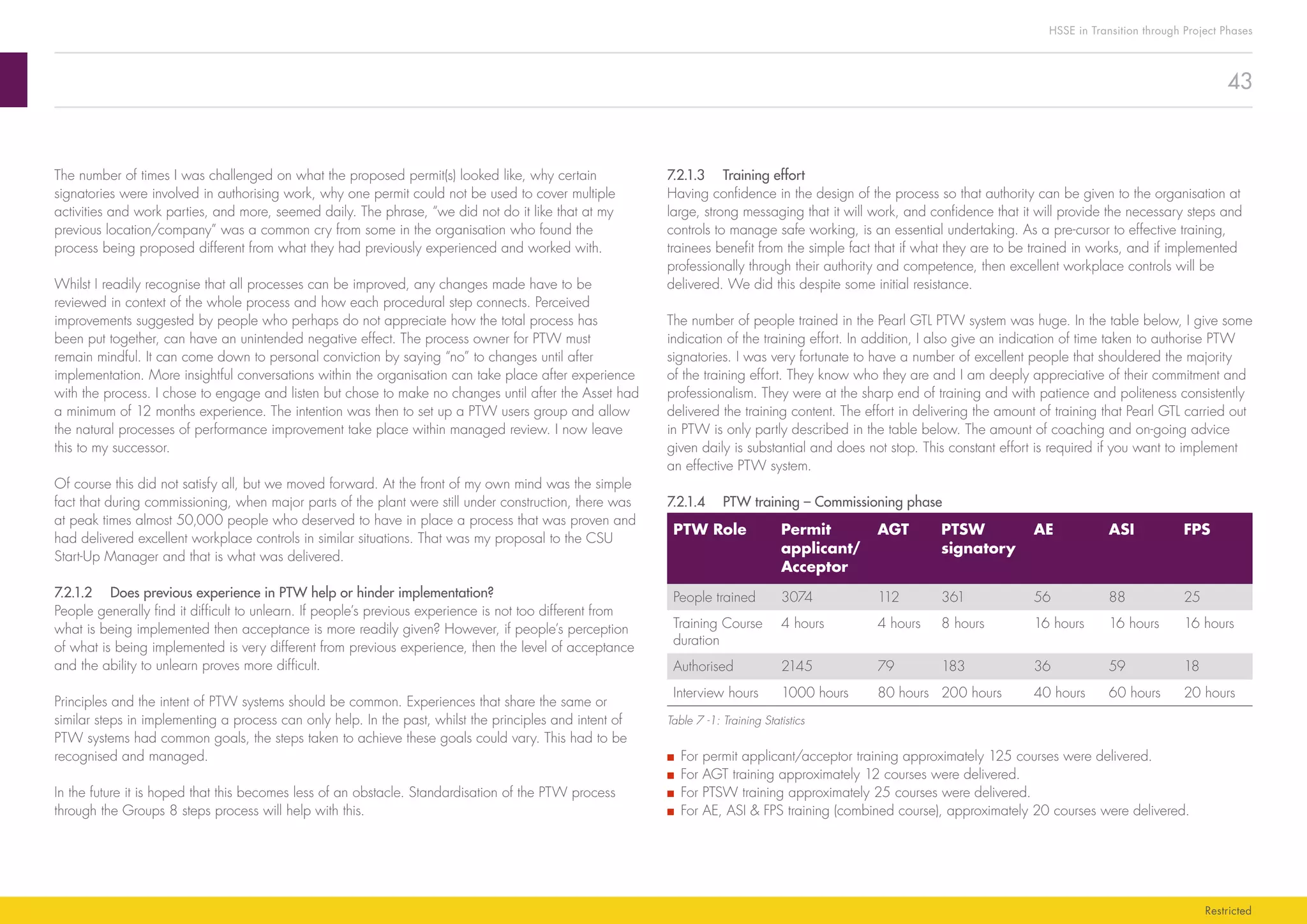

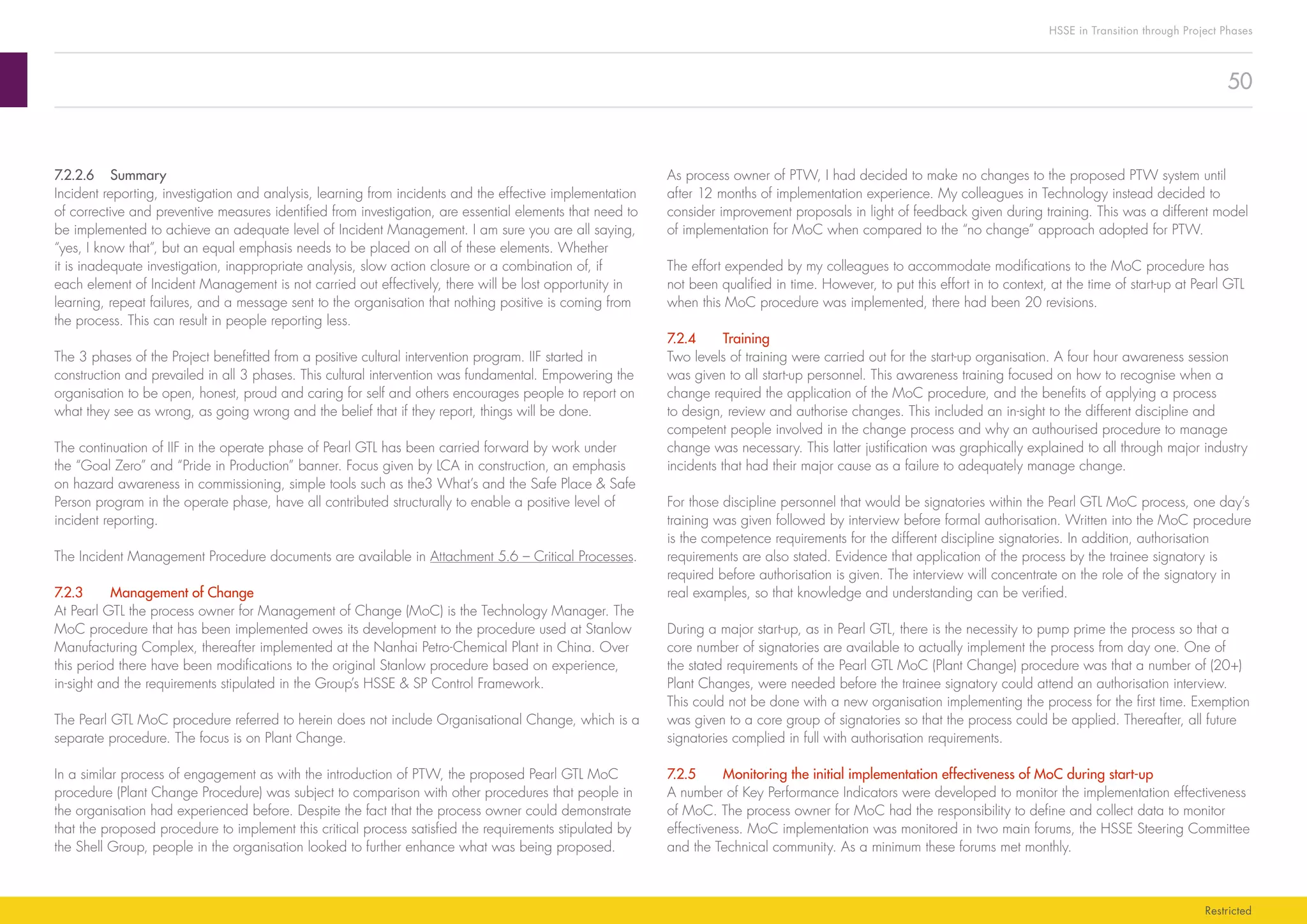

Figure 32: MOC/TPC Flow Scheme

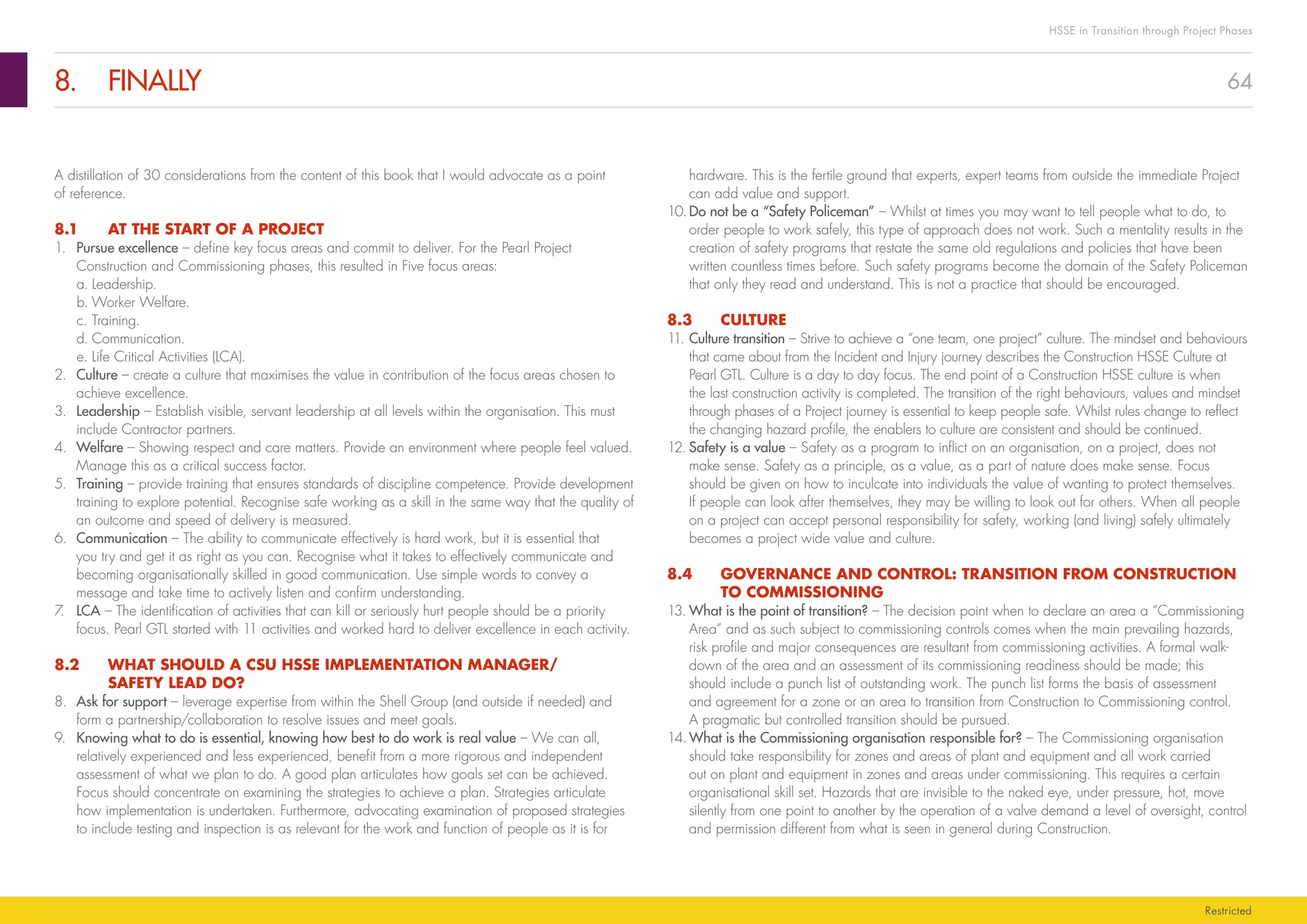

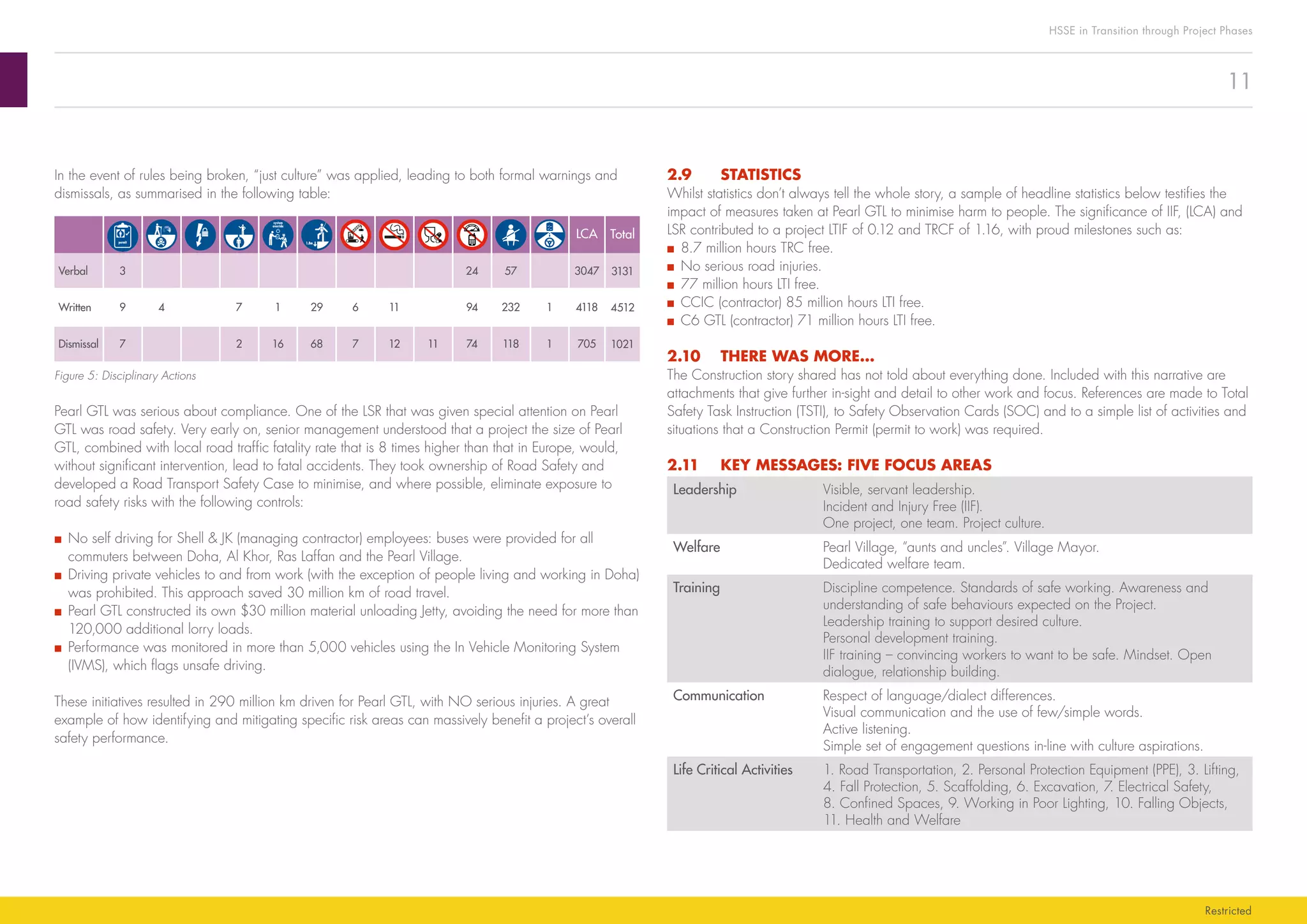

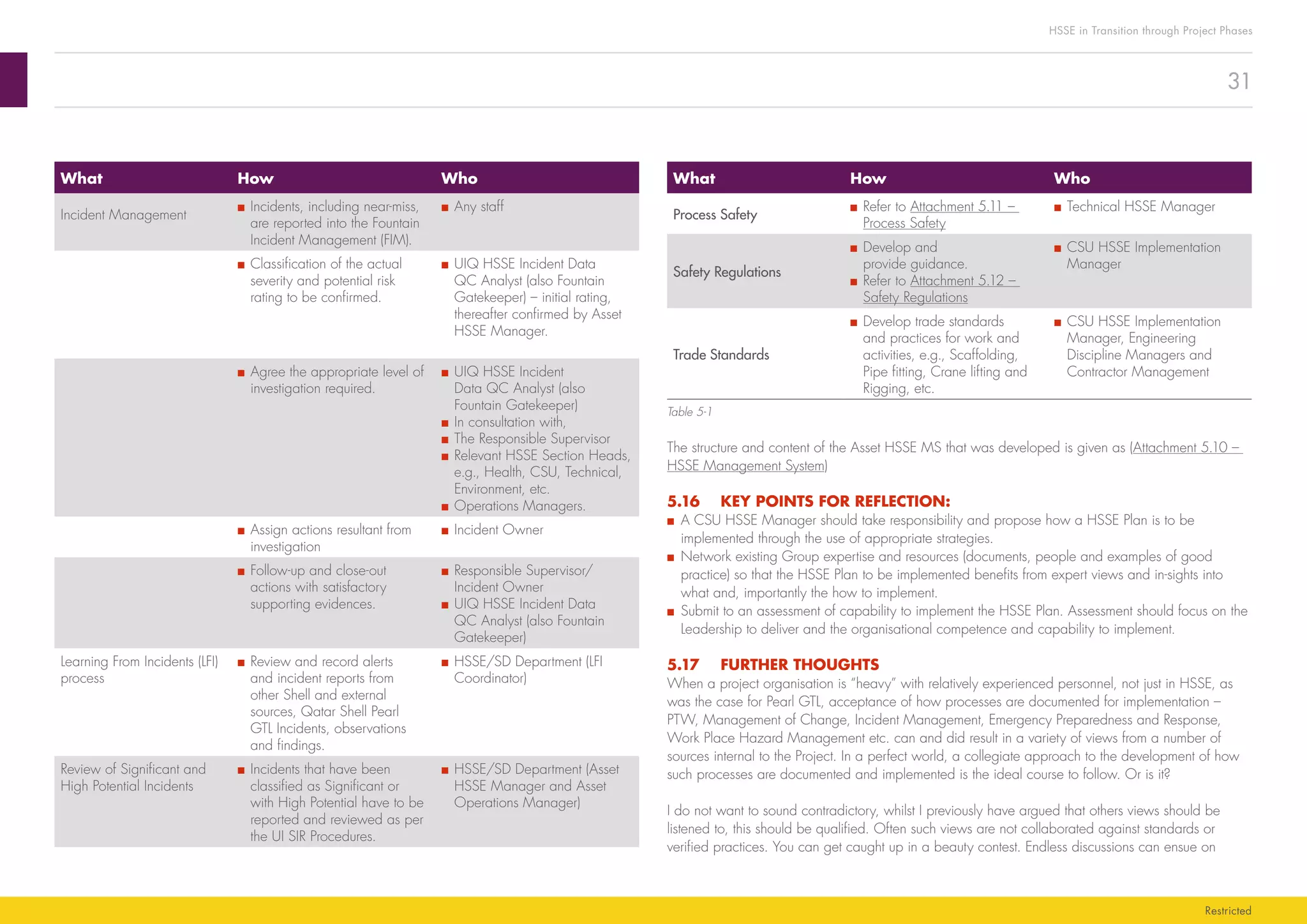

The table below represents the KPI used during start-up year (2011).

Key Performance Indicators Target

1. The number of changes raised during the reporting period (month) Track

2. Number of PCR taken into operation without readiness review completed Zero

3. PCR documentation not updated within 90 days of PCR implementation Zero

4. Temporary PCR overdue for review Zero

Table 7-3: MOC KPIs

The above were the set of KPI that were initially tracked.

The number of changes being carried out was deemed important initially as a crude measure to

monitor the amount of change taking place. The amount of change during start-up and in the first 12

months of operation was considerable. Much of this was necessary to correct/improve on equipment

and equipment design parameters not meeting start-up requirements. A large proportion of these

changes were software. As well as giving a crude number as an indicator, further granularity was

also given in the type of change (software, hardware etc.).

KPI 2 monitored the level of organisational (mainly operations) readiness and preparedness to accept

the change and to understand the implications of the change. This could include training, awareness,

procedural updates etc. If the number of changes is large, the work load on the Operations nominee

(in steady state operation this is normally an Operations Day Supervisor) is extremely high, and from

Pearl GTL’s experience, cannot be done by one person.

KPI 3 is self explanatory. This focused on trying to ensure that documentation was kept current. A big

effort is required to do this.

KPI 4 focused on the review and continued authorisation of Temporary Plant Changes.

KPI 2 3 were the most challenging indicators to satisfy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eff722ba-0272-4a3c-bf81-b1a5459e559b-150609010308-lva1-app6892/75/896405-HSSE_v03-51-2048.jpg)