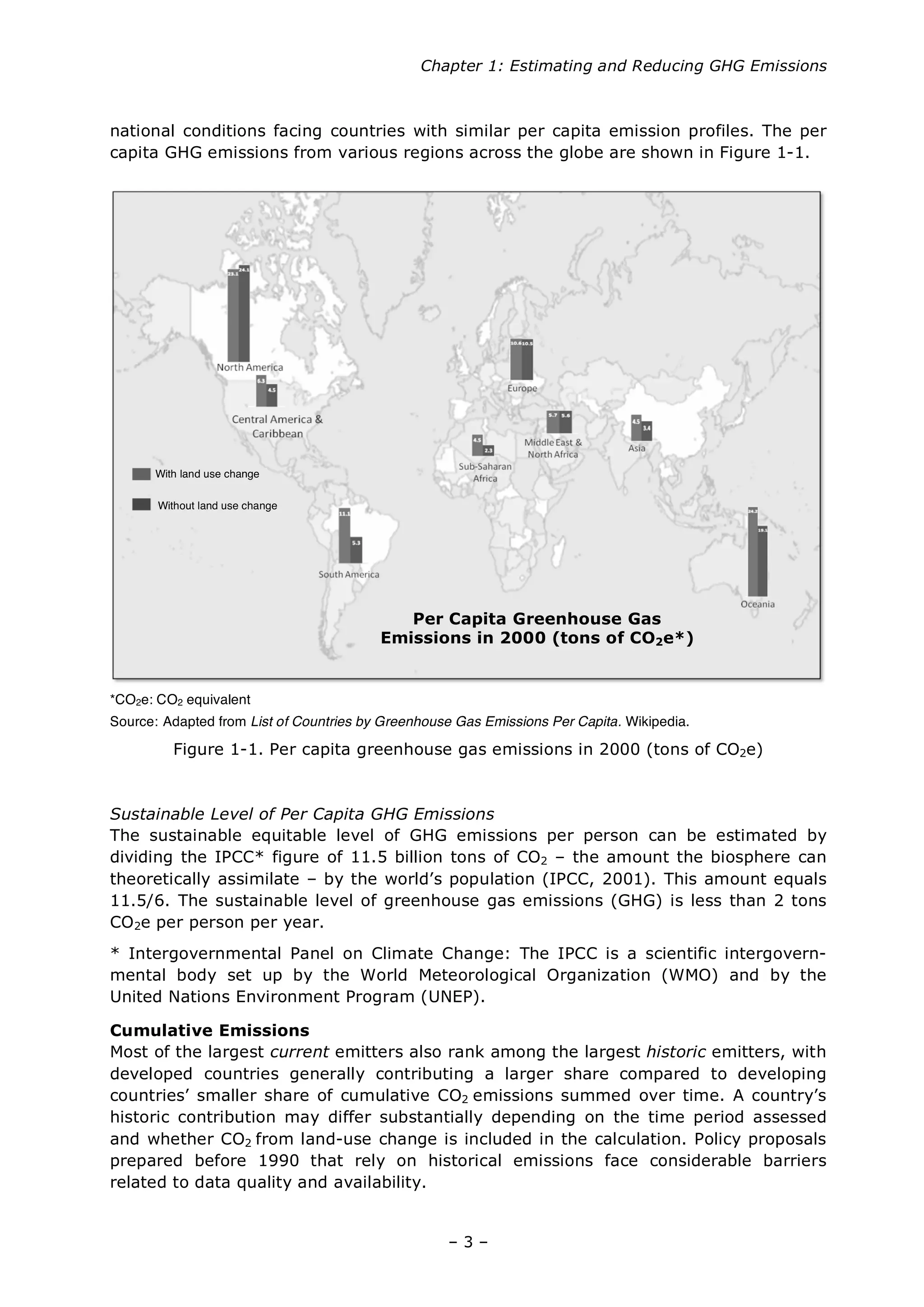

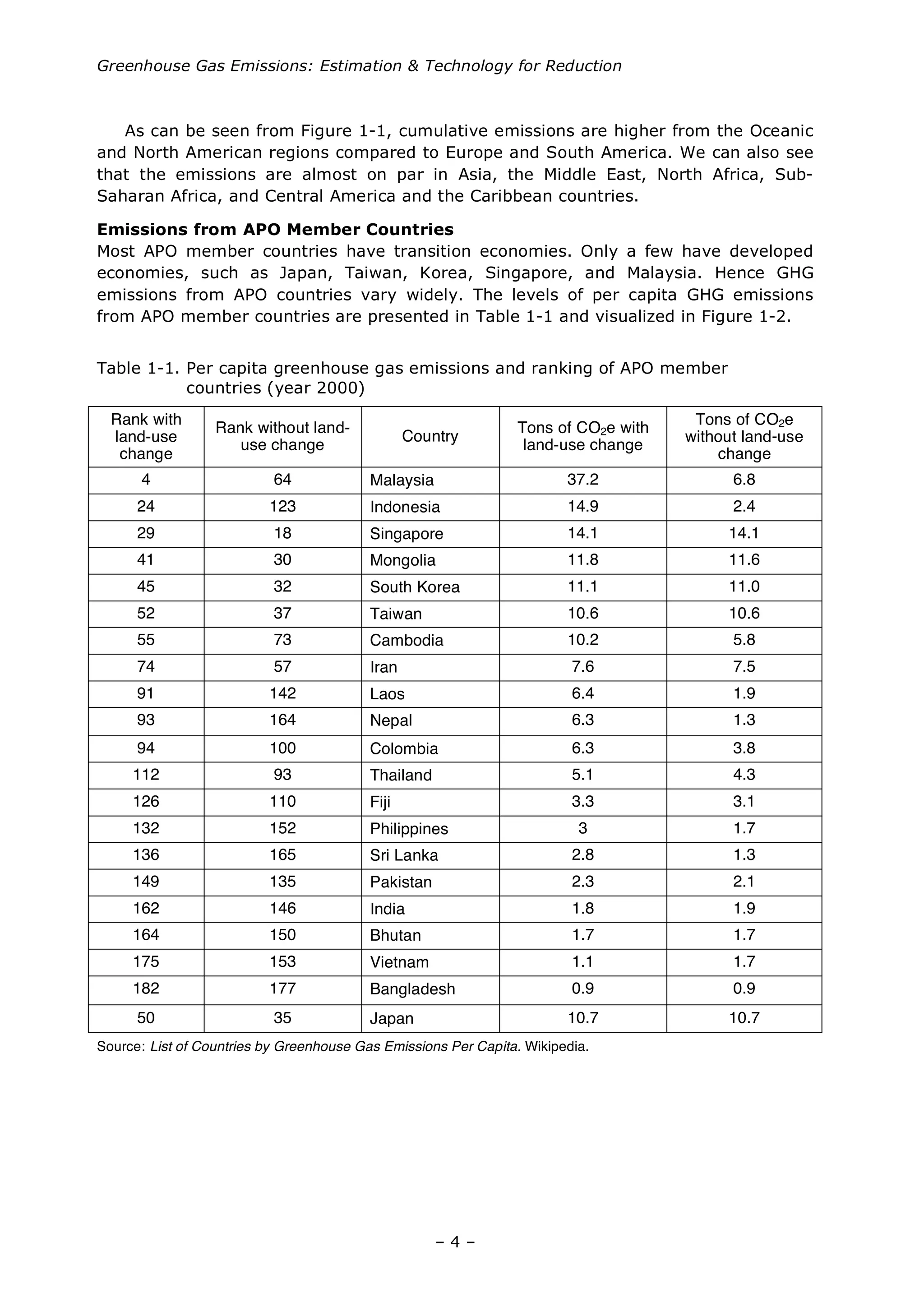

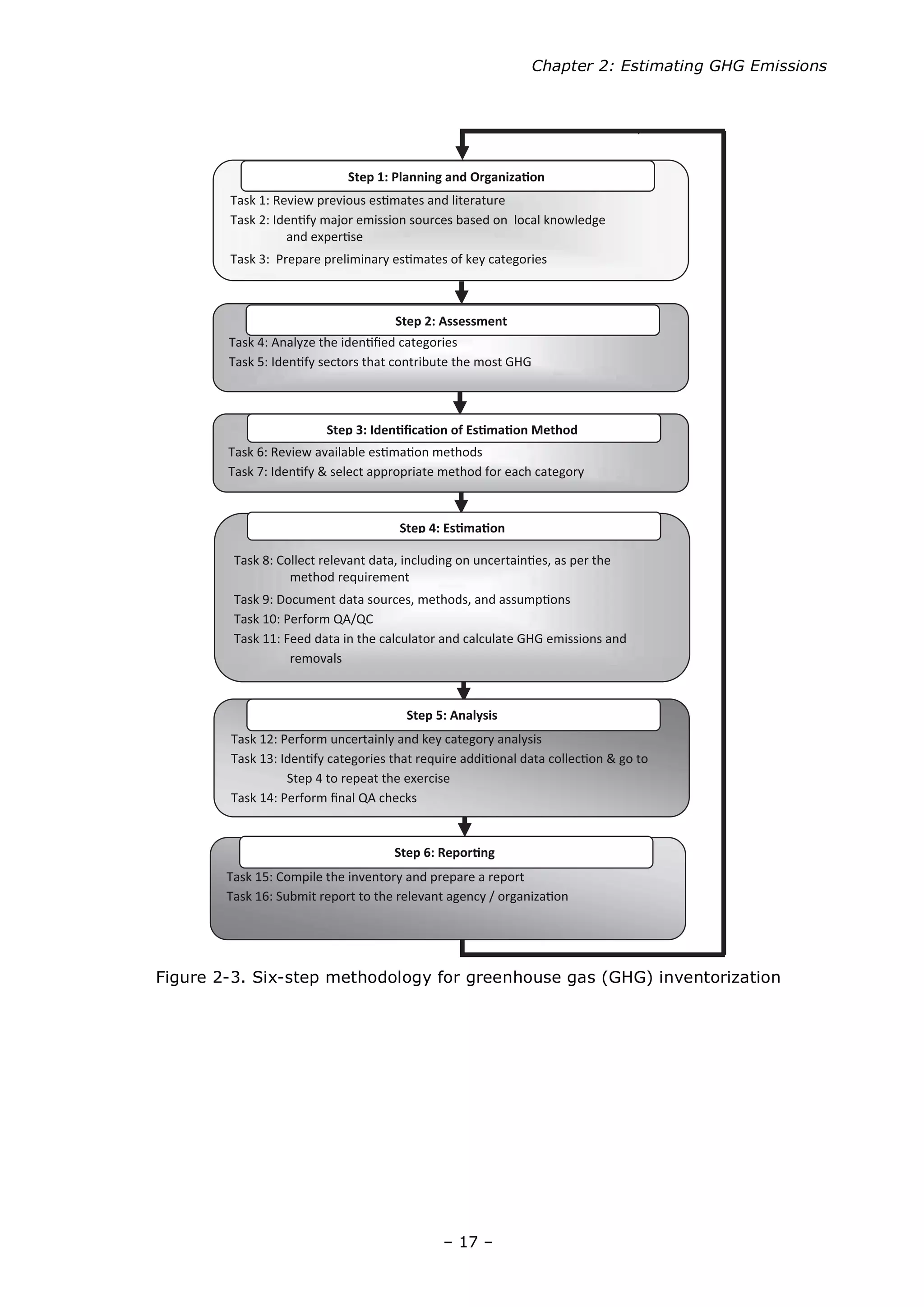

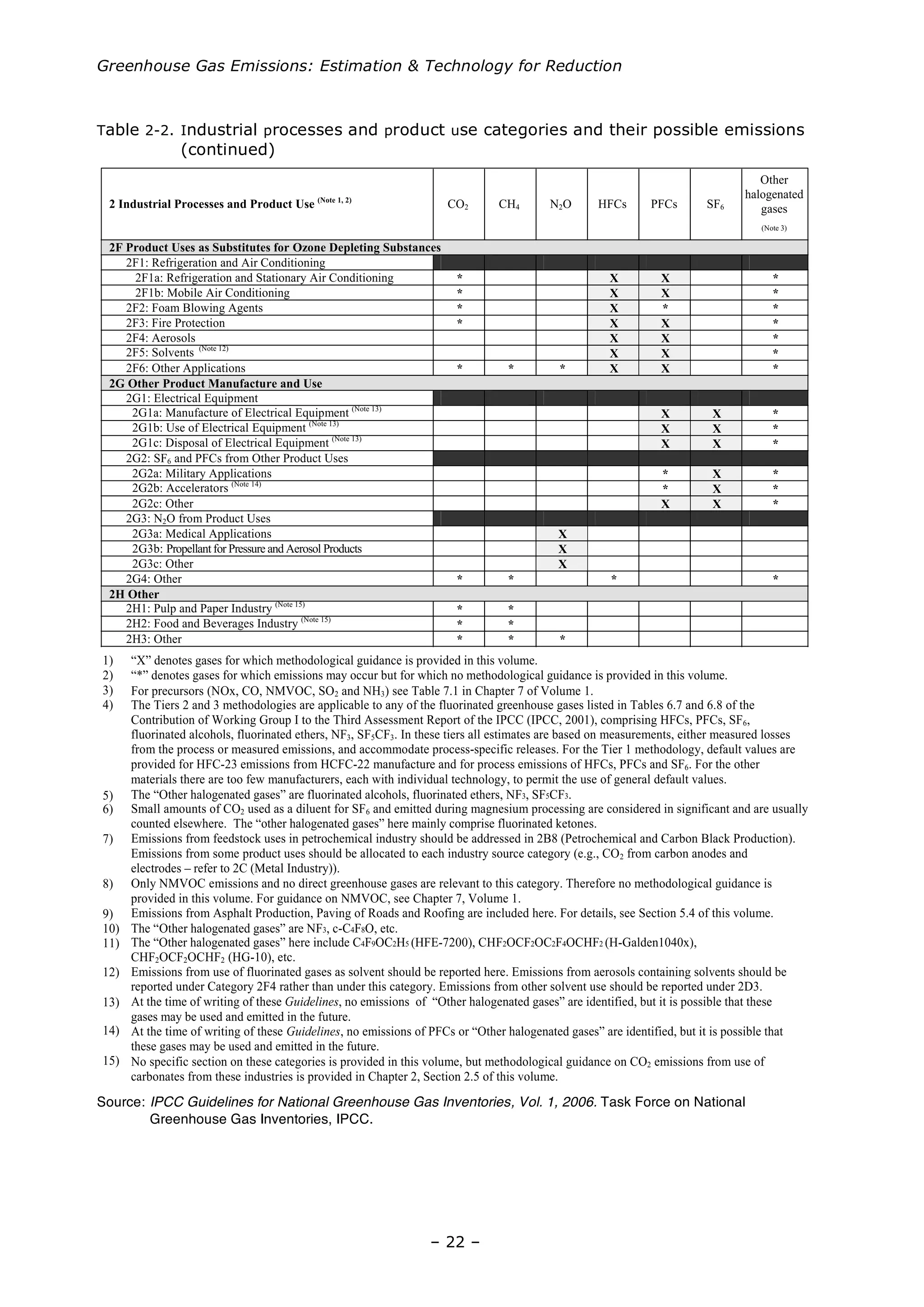

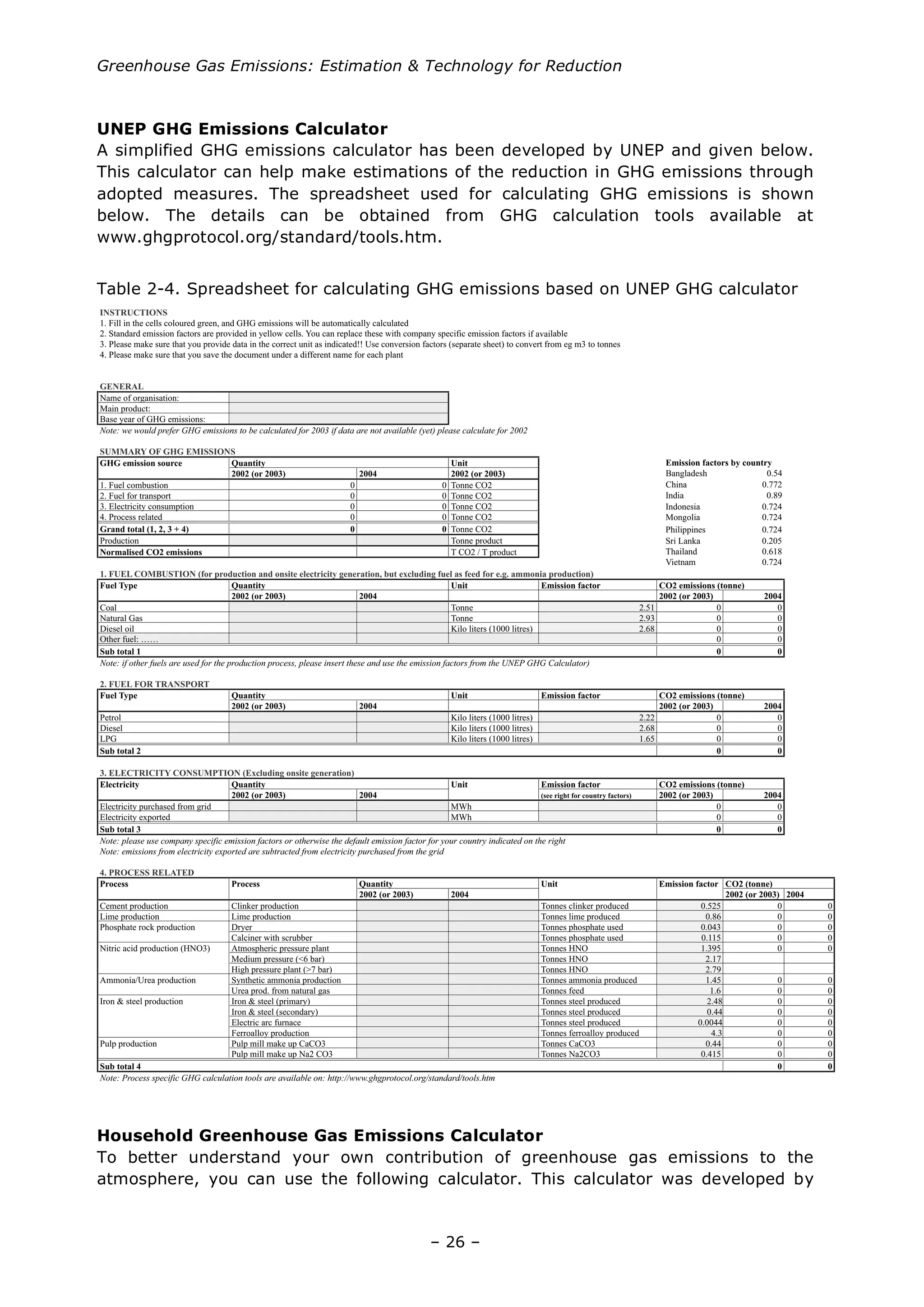

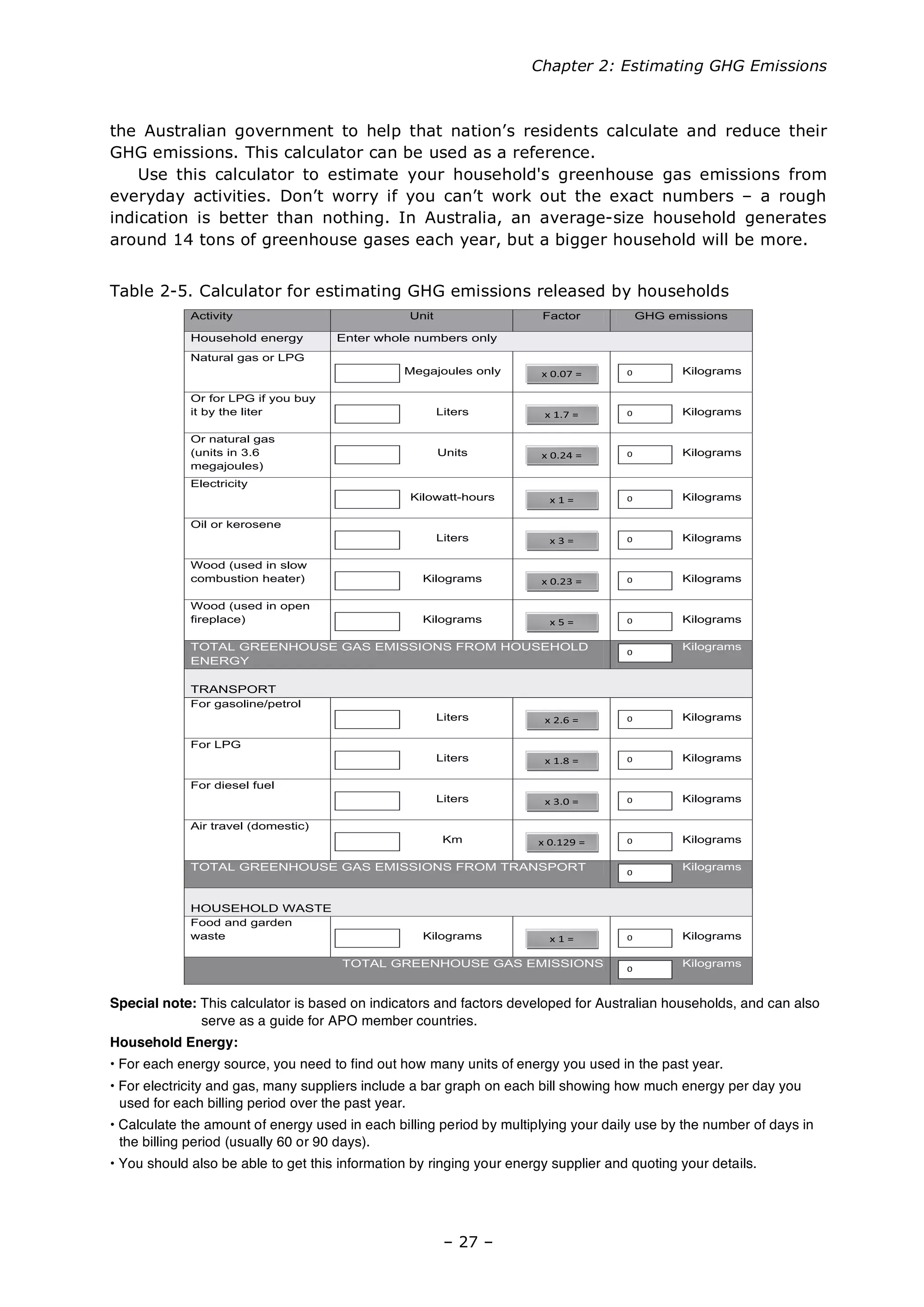

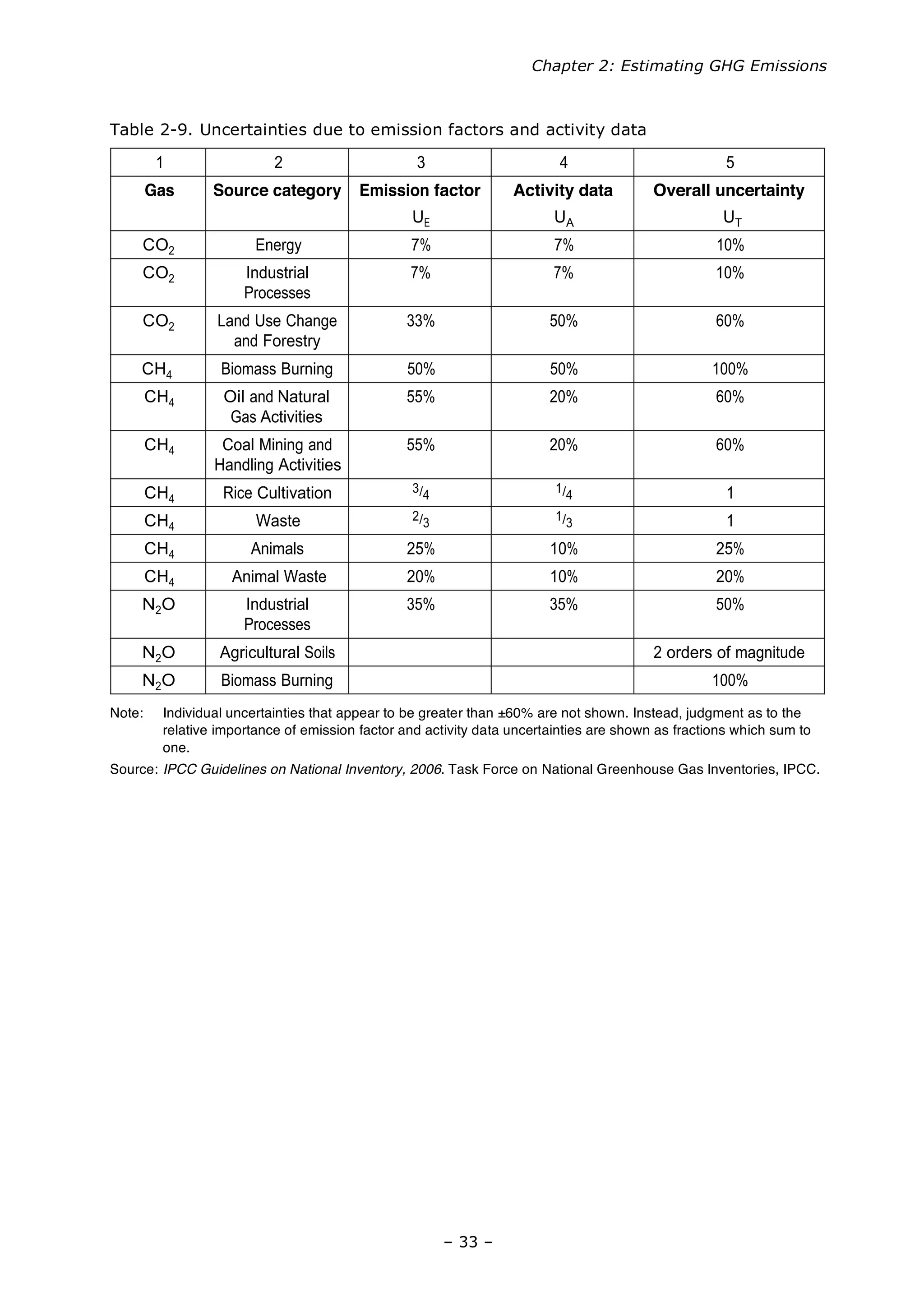

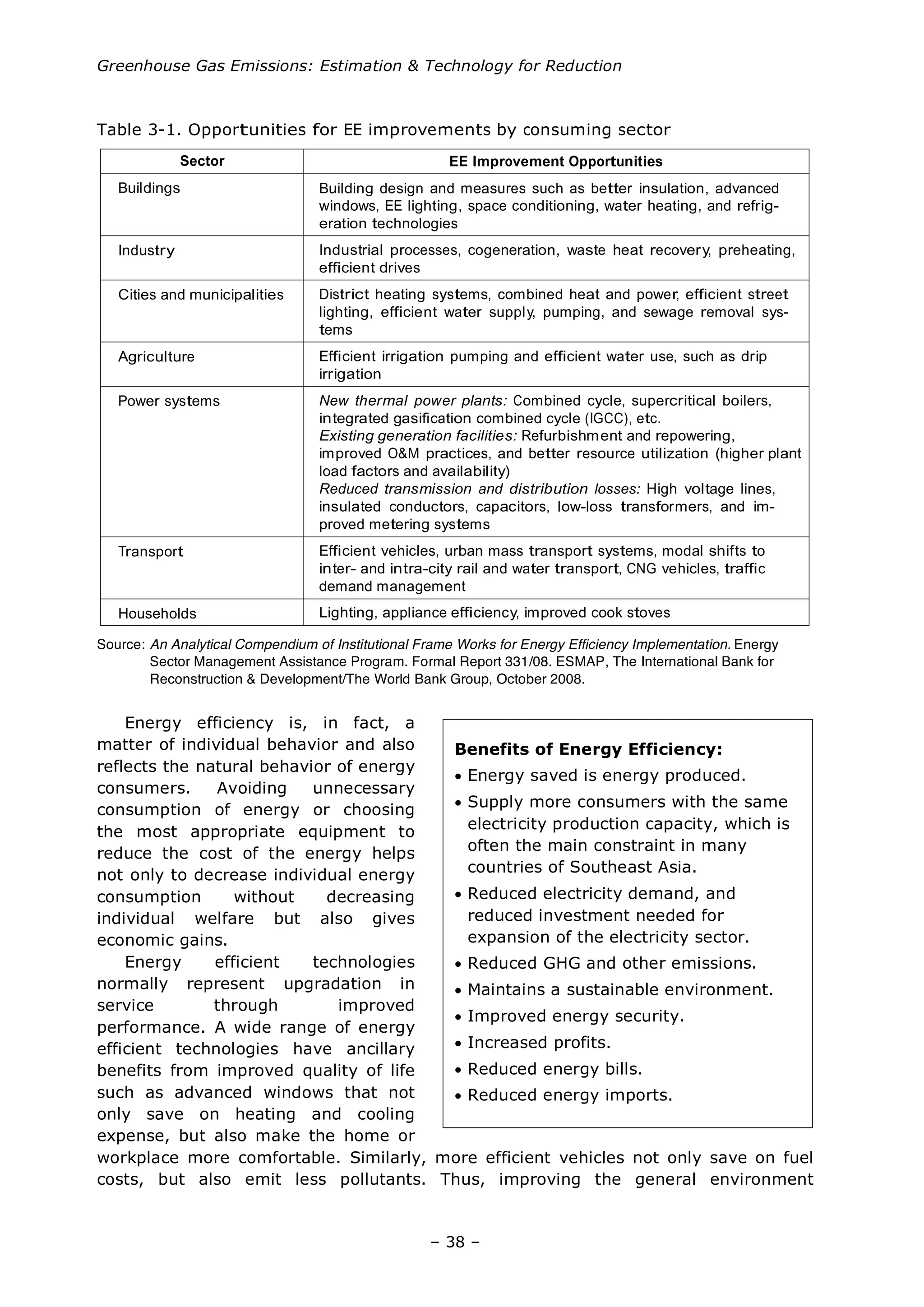

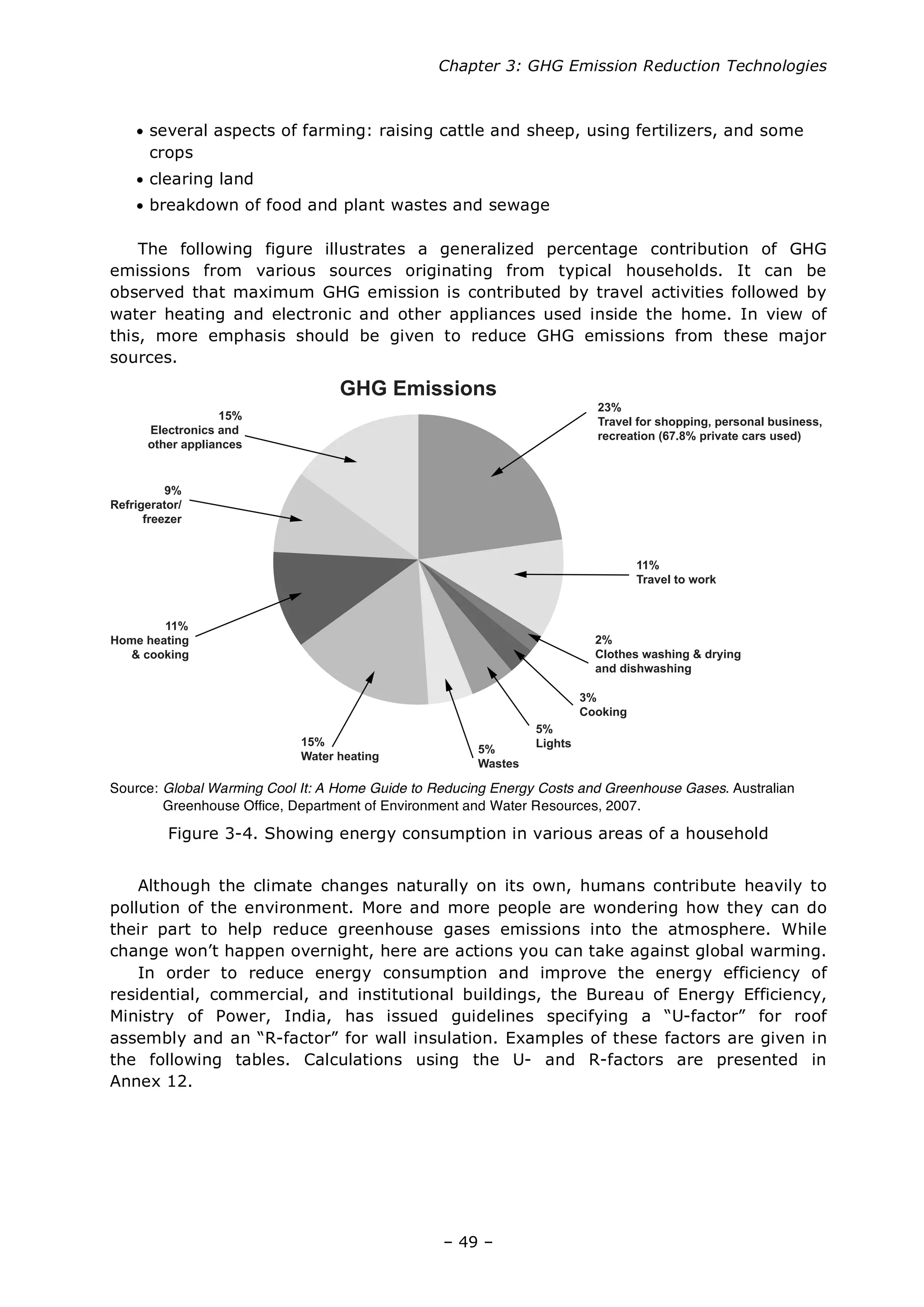

This document provides comprehensive guidelines for estimating and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, emphasizing the role of human activities in climate change and the necessity for mitigation strategies. It outlines the global scenario regarding GHG emissions, estimation methods, technologies for emission reduction, and includes various annexes for detailed data and calculations. The publication aims to assist Asian Productivity Organization member countries in addressing climate change through informed action plans and awareness.

![Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Estimation & Technology for Reduction

– 82 –

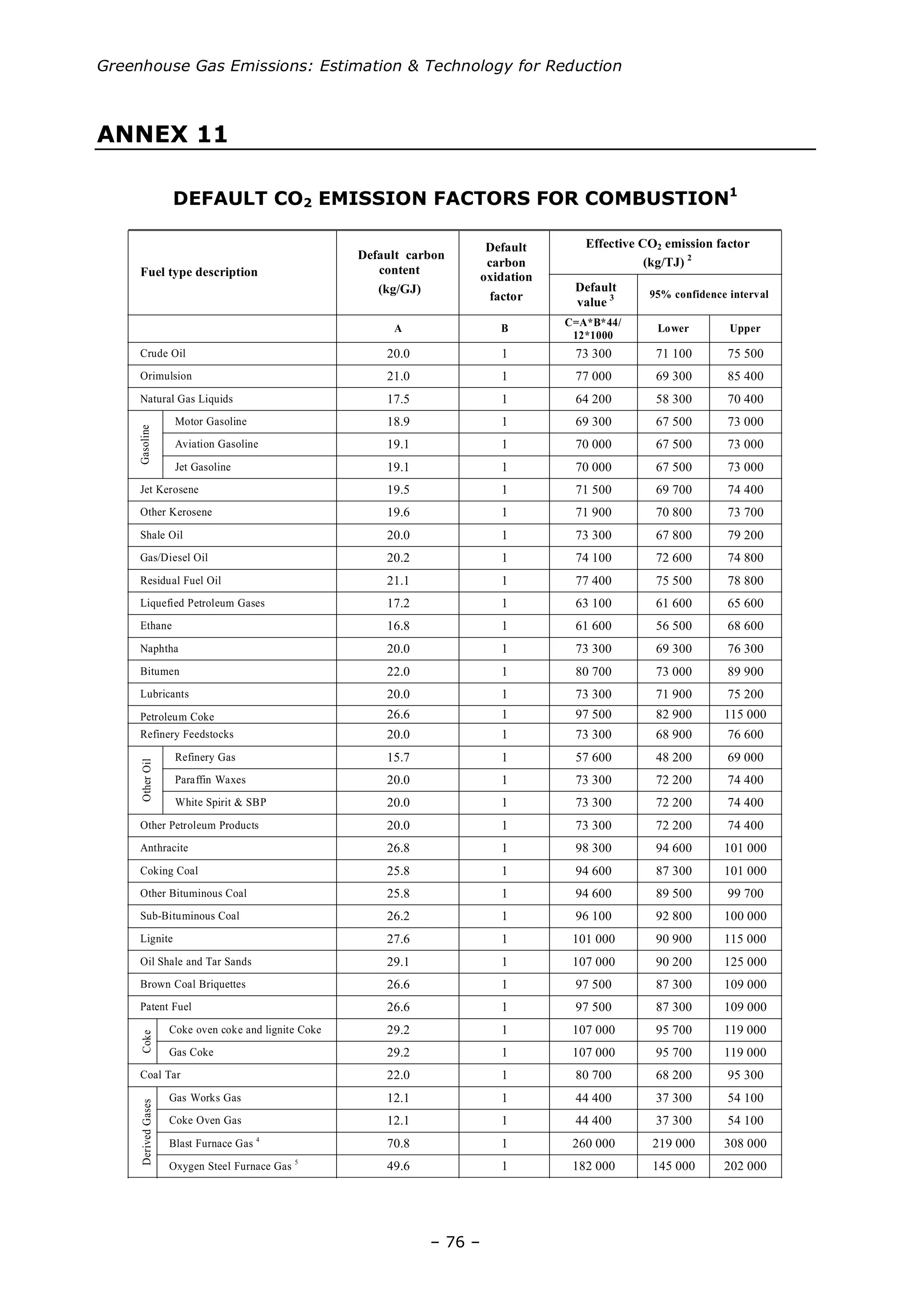

Motor gasoline

Motor gasoline consists of a mixture of light hydrocarbons distilling between 35° and

215°C. It is used as a fuel for land-based spark ignition engines. Motor gasoline may

include additives, oxygenates, and octane enhancers, including lead compounds such

as TEL (tetraethyl lead) and TML (tetramethyl lead).

Global warming potential (GWP)

GWP is defined as the cumulative radiative forcing effects of a gas over a specified

time horizon resulting from the emission of a unit mass of gas relative to a reference

gas. The reference gas is considered as carbon dioxide. The molecular weight of

carbon is 12, and that of oxygen is 16; therefore the molecular weight of carbon

dioxide is 44 (12 + [16 x 2]), as compared to 12 for carbon alone. Thus carbon

comprises 12/44ths of carbon dioxide by weight.

Greenhouse gases

The current IPCC inventory includes six major greenhouse gases.

Three direct greenhouse gases are included: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4),

nitrous oxide (N2O); and three precursor gases are included: carbon monoxide (CO),

oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs).

Other gases that also contribute to the greenhouse effect are being considered for

inclusion in future versions of the Guidelines.

HFCs

See Hydrofluorocarbons.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HCFC)

Hyrocarbon derivatives consisting of one or more halogens that partly replace the

hydrogen. The abbreviation HCFC followed by a number designates a chemical product

of the chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) family.

IPCC

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is a special intergovernmental

body established by UNEP and the WMO to provide assessments of the results of

climate change research to policy makers. The Greenhouse Gas Inventory Guidelines

are being developed under the auspices of the IPCC and will be recommended for use

by parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC).

LULUCF

Land use, land-use change, and forestry.

Montreal Protocol

This is the international agreement that requires signatories to control and report

emissions of CFCs and related chemical substances that deplete the Earth’s ozone

layer. The Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987 in accordance with the broad

principles for protection of the ozone layer agreed in the Vienna Convention (1985).

The Protocol came into force in 1989 and established specific reporting and control

requirements for ozone-depleting substances.

OECD

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, which is a regional

organization of free-market democracies in North America, Europe, and the Pacific.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gp-19-gge-160526165707/75/Greenhouse-gas-emissions-estimation-and-reduction-92-2048.jpg)