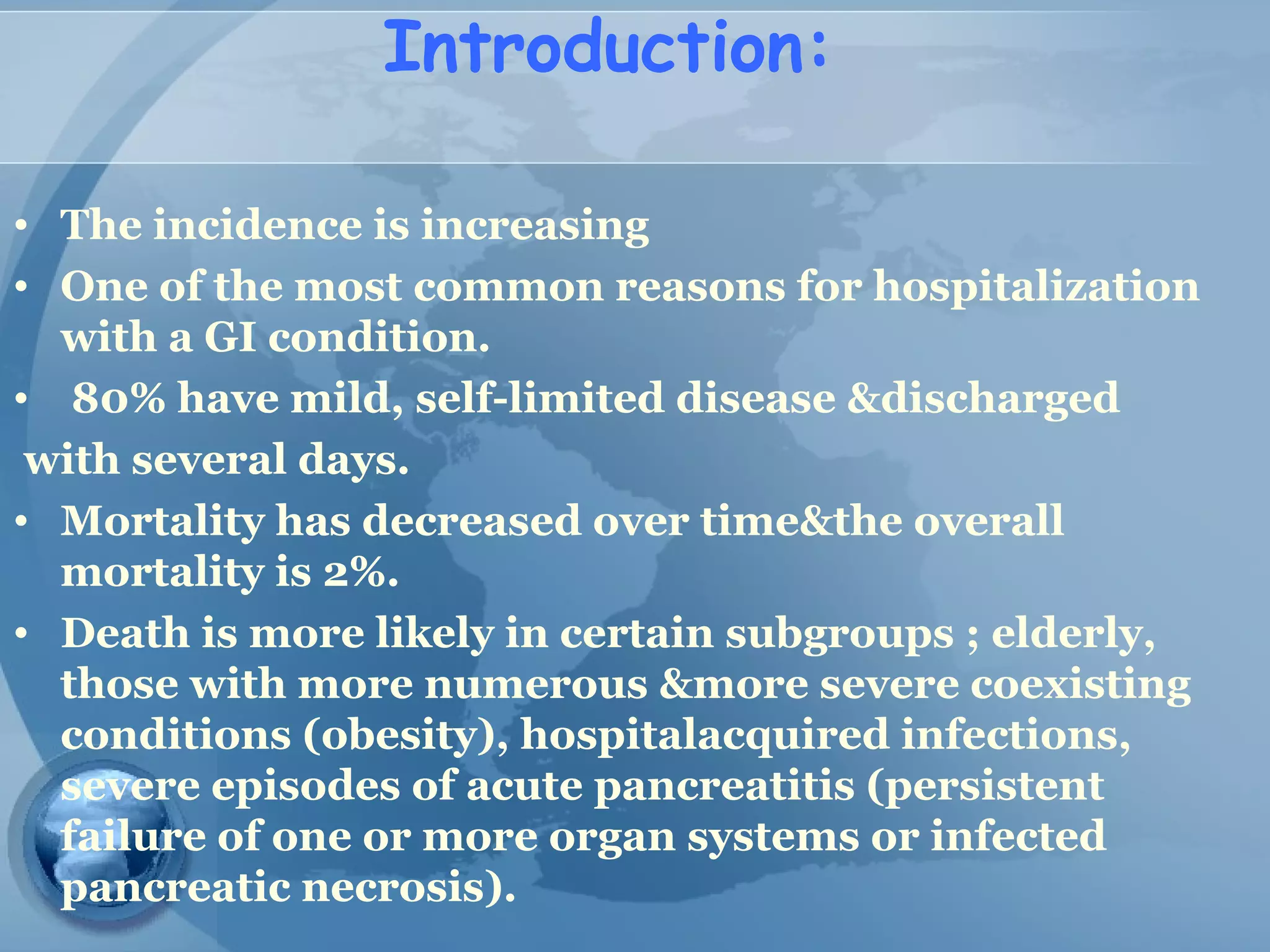

This document provides information on acute pancreatitis including:

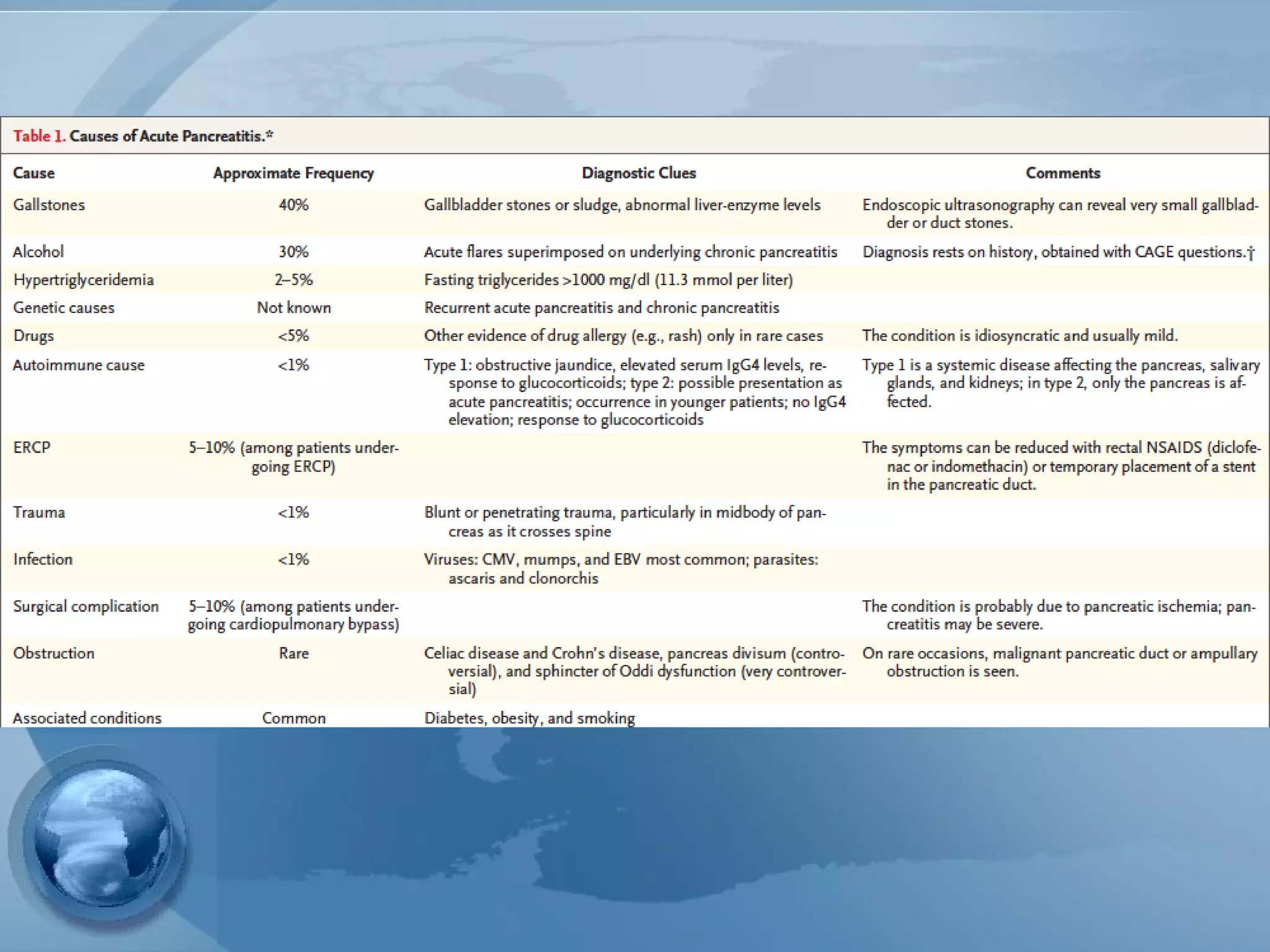

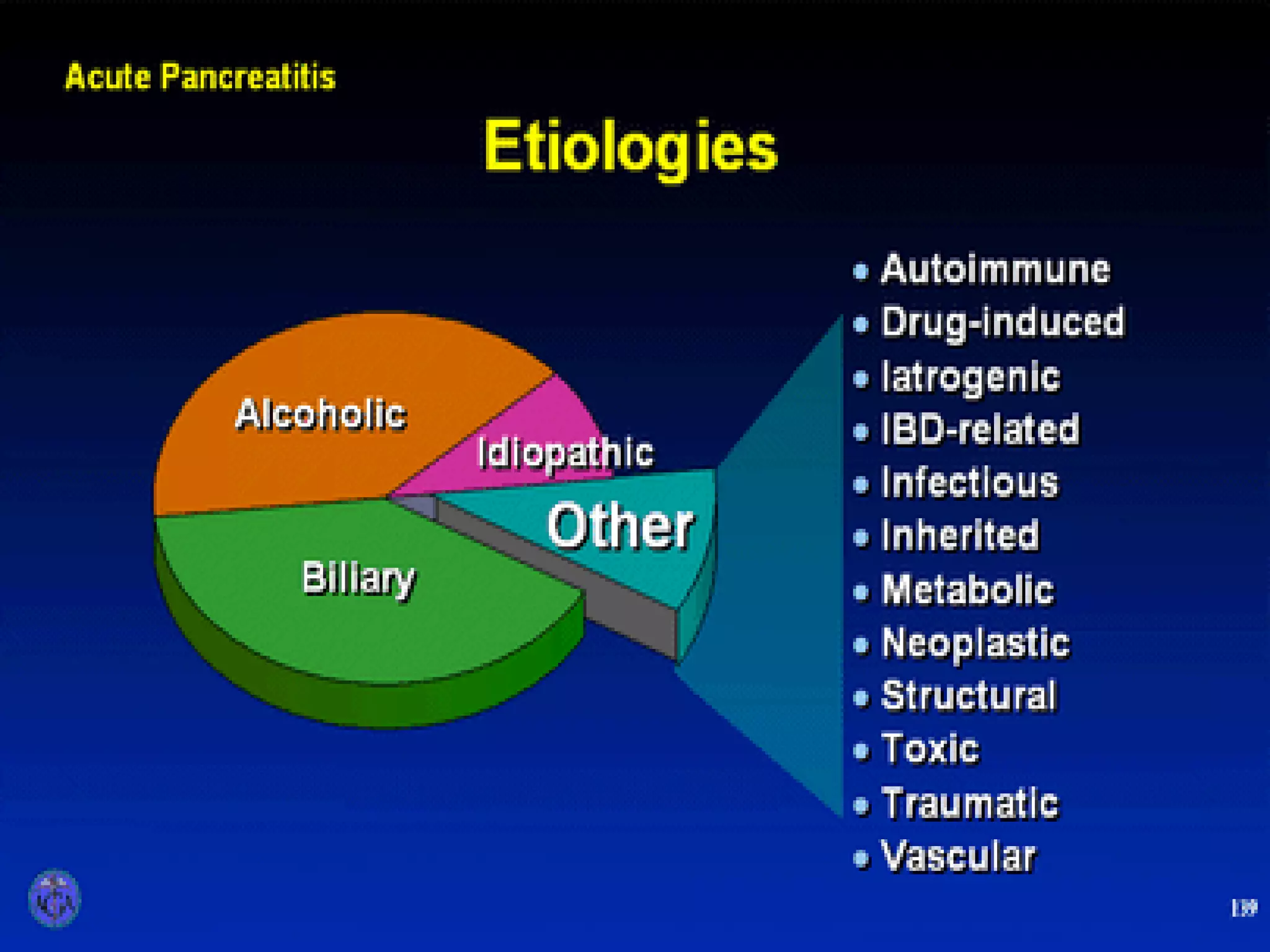

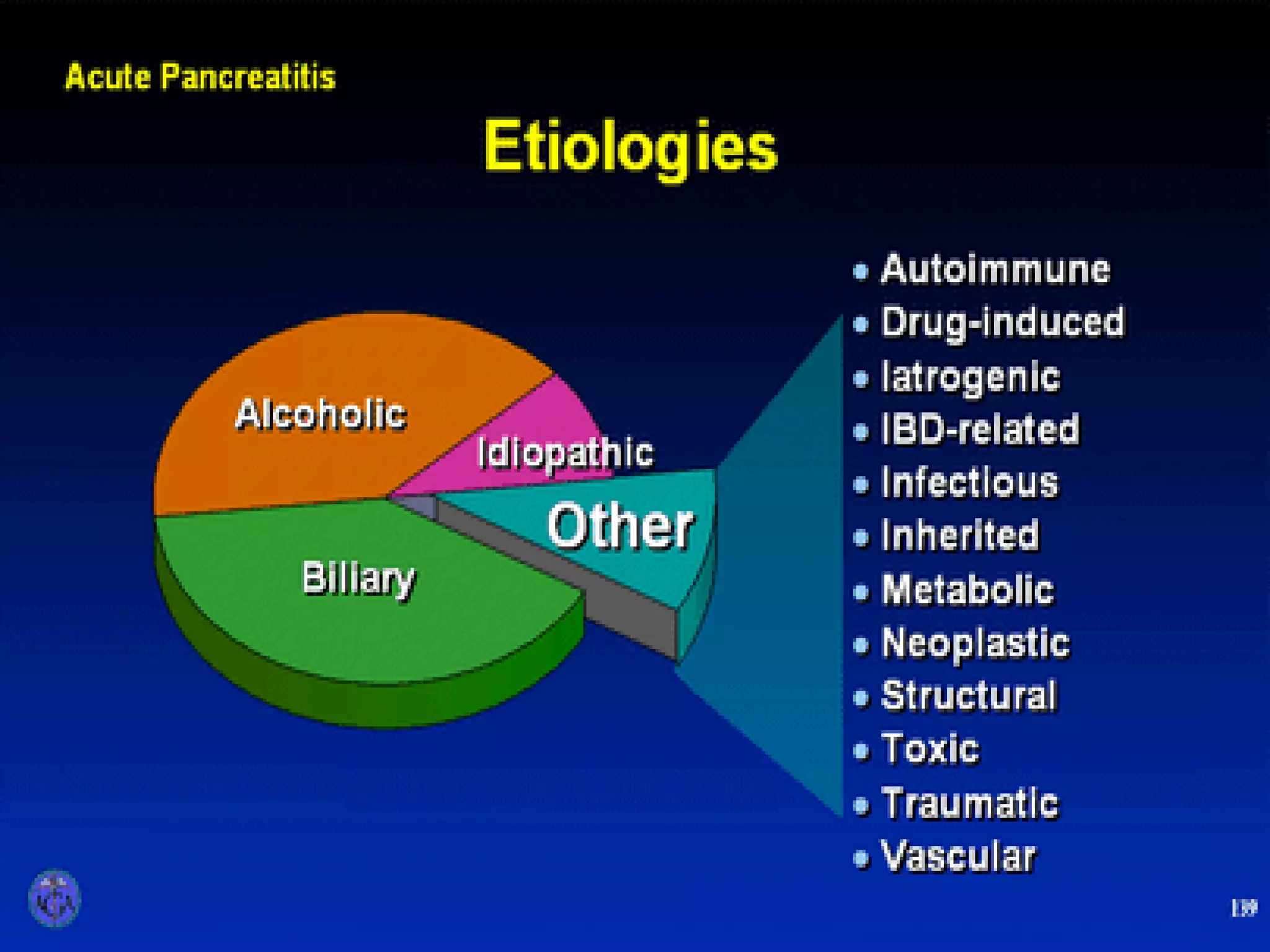

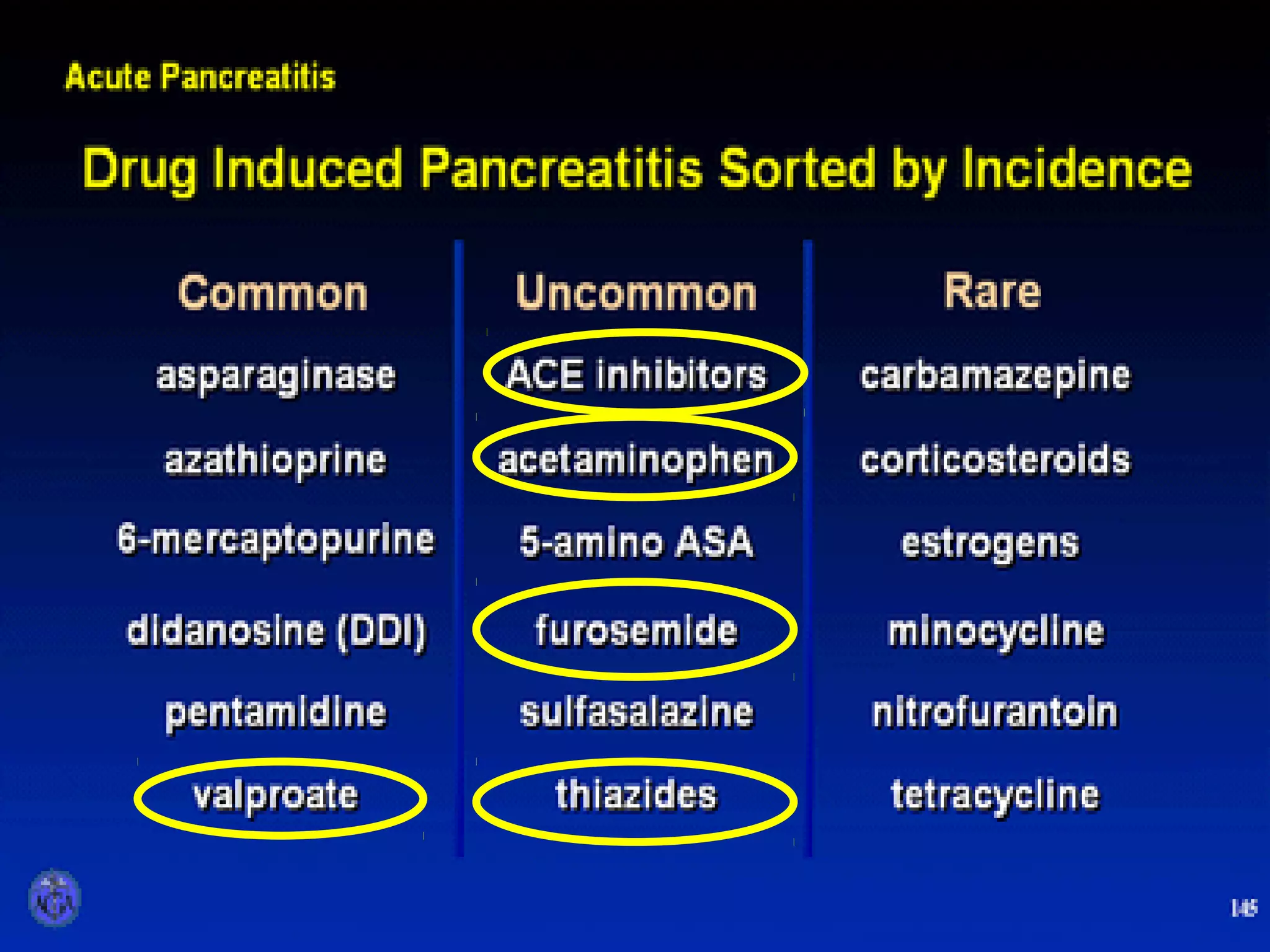

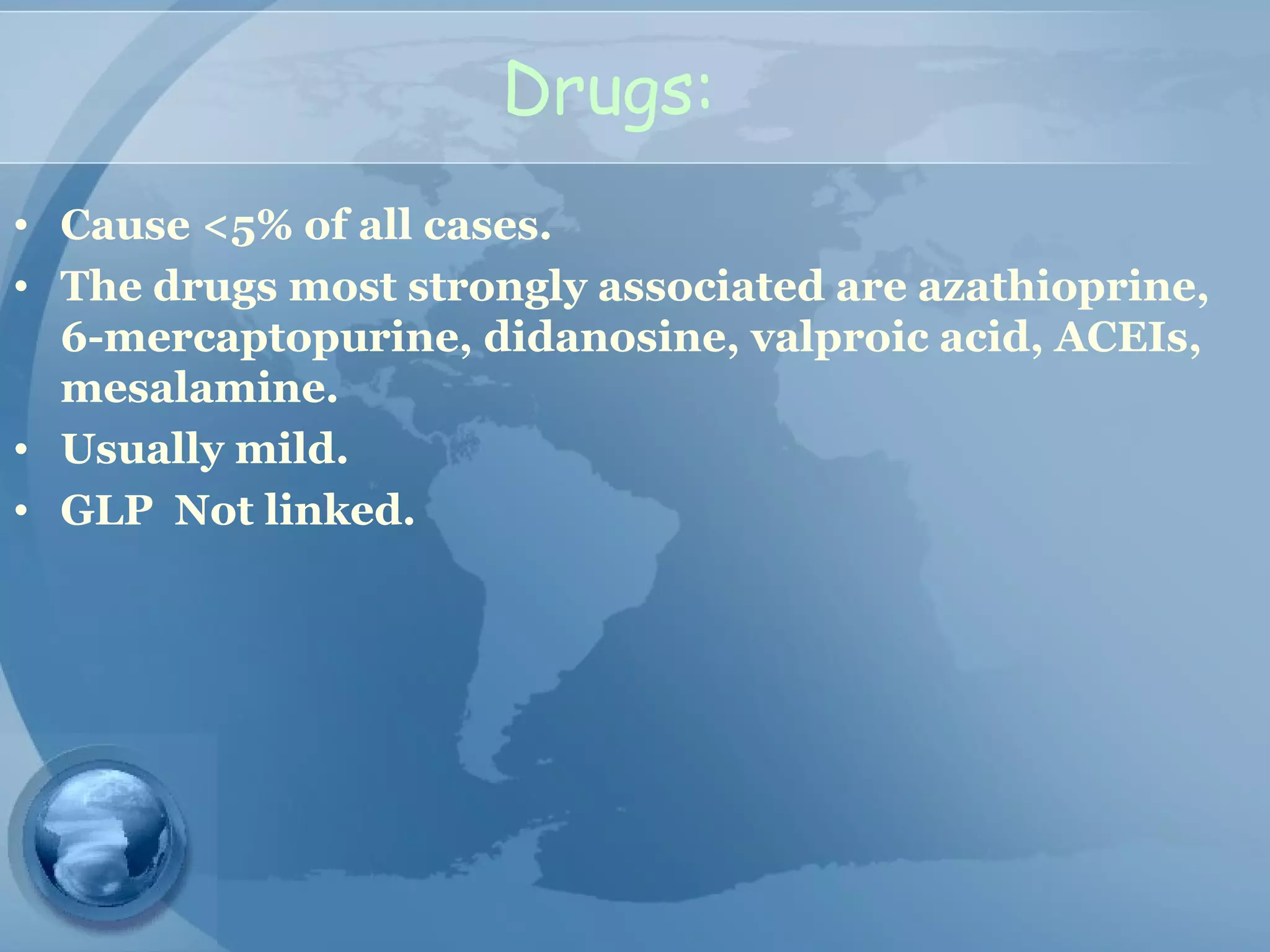

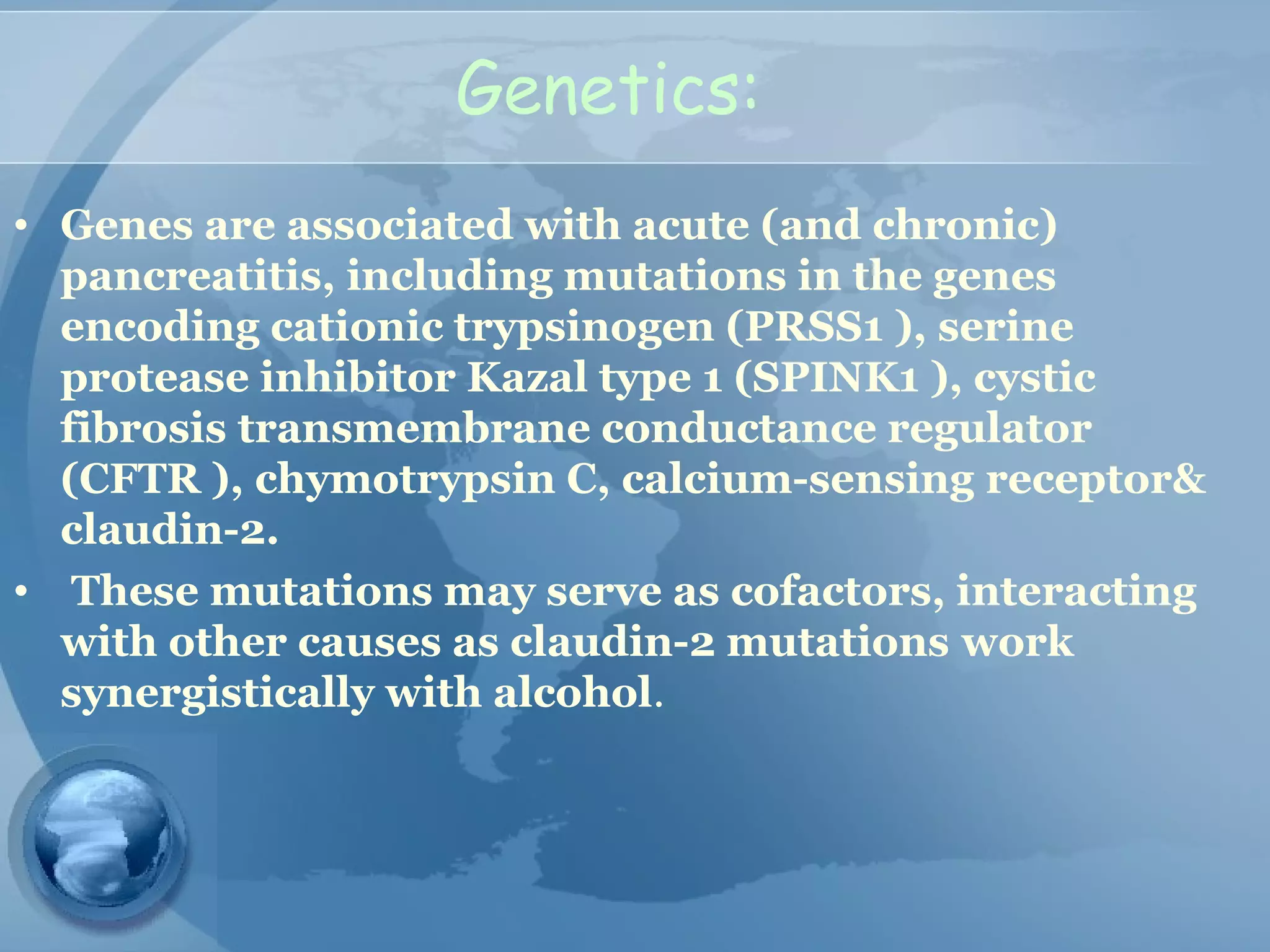

- Etiology is often gallstones or alcohol use. Other causes include drugs, genetics, obesity, and diabetes.

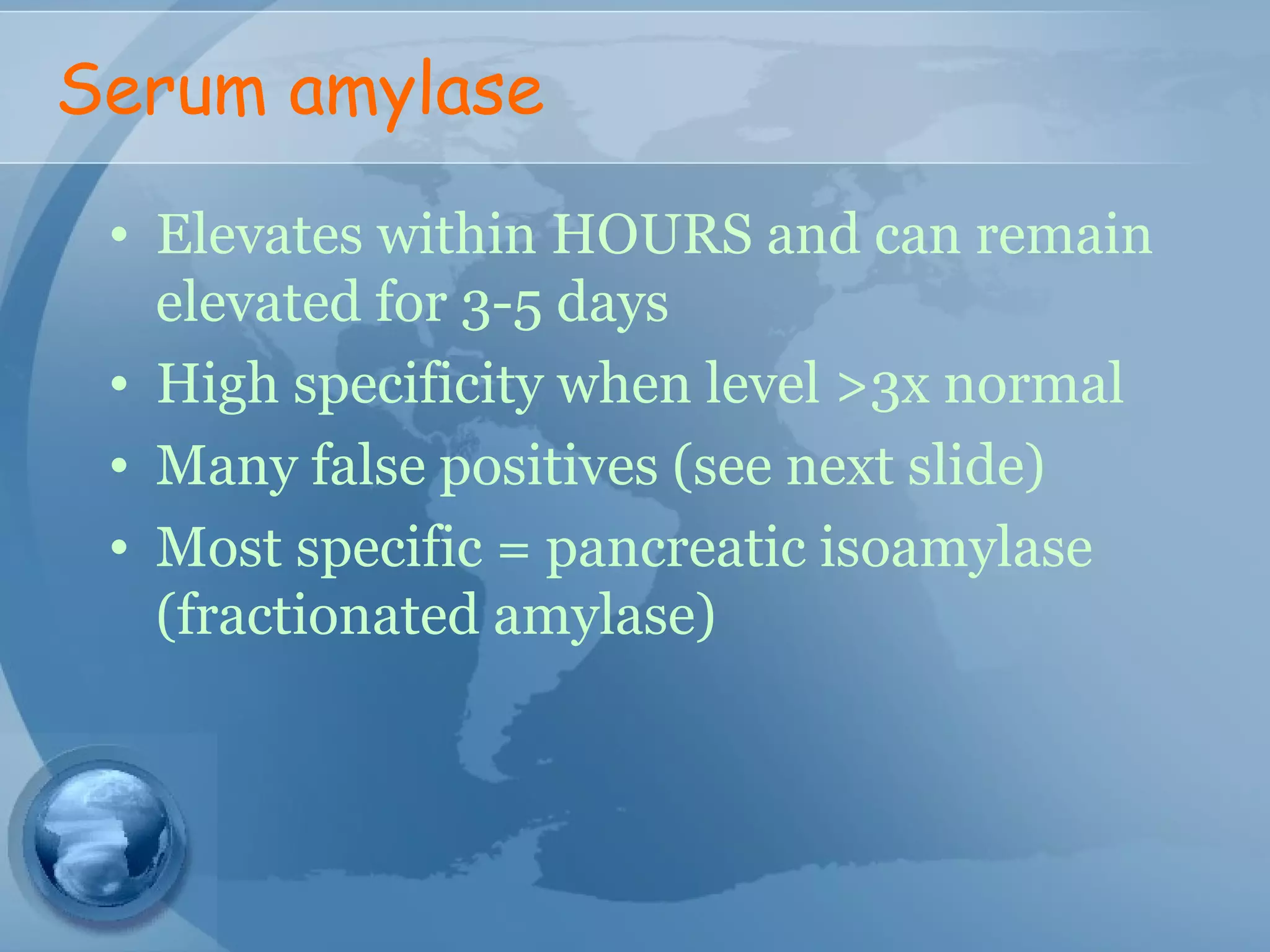

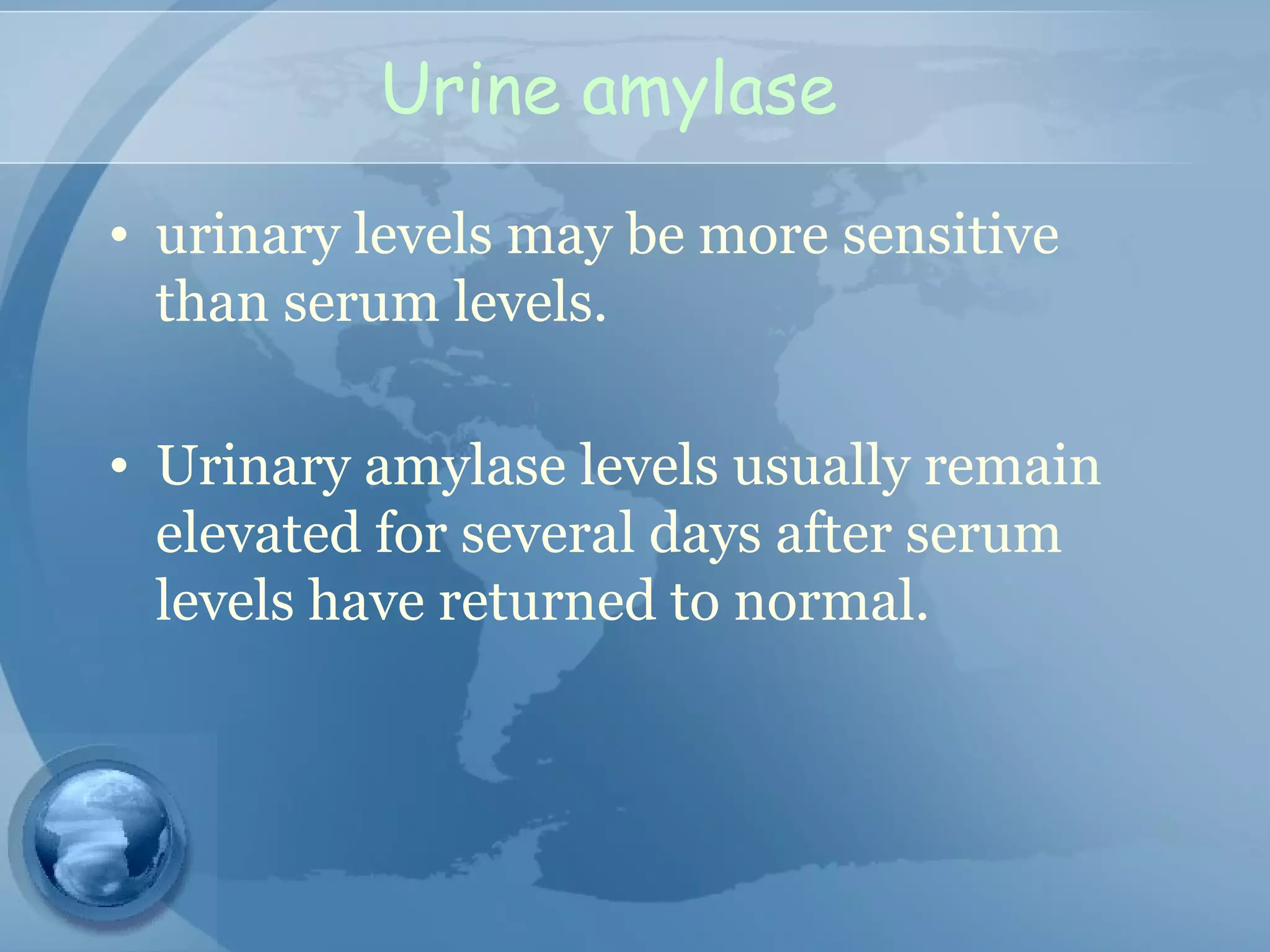

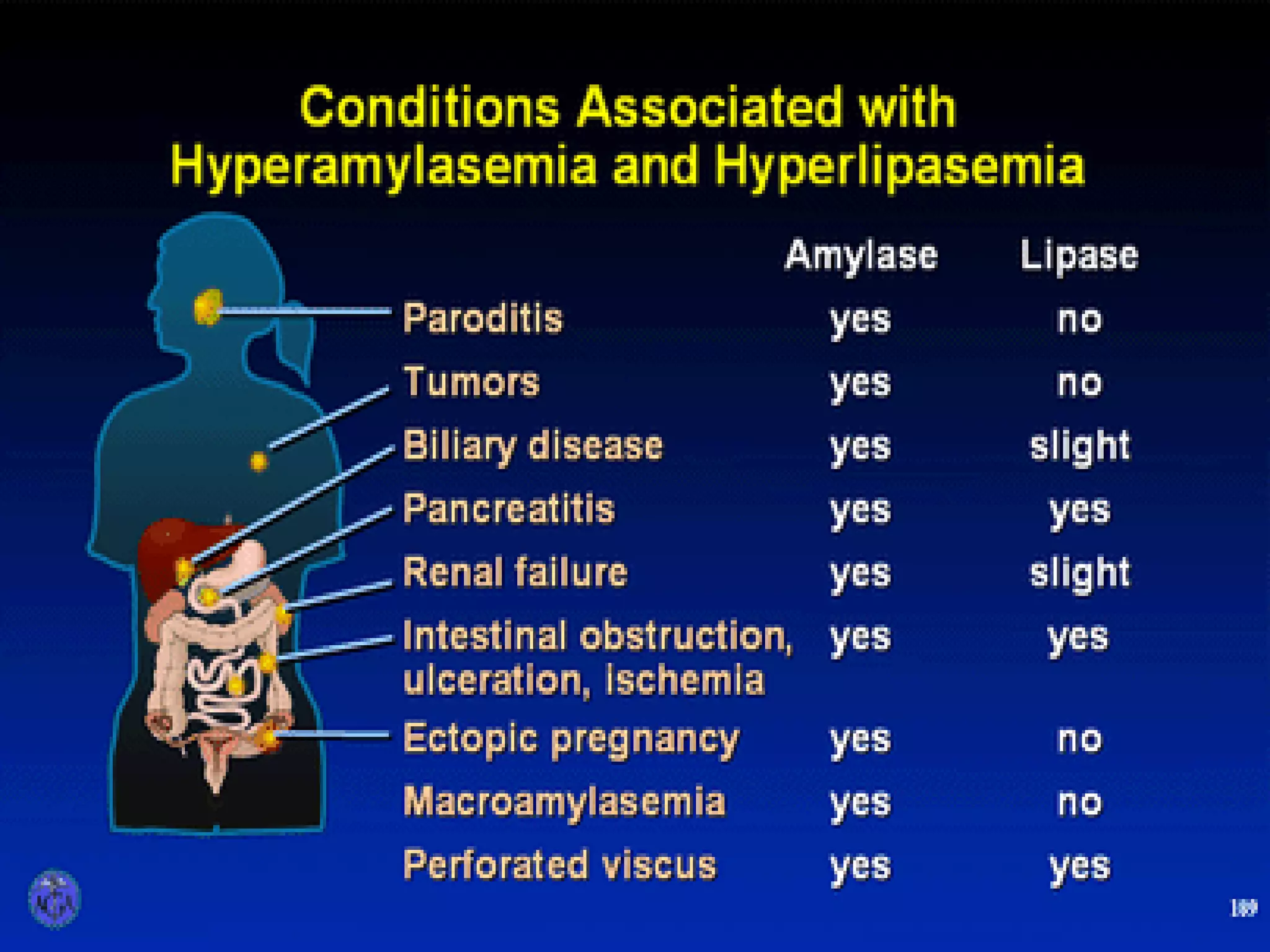

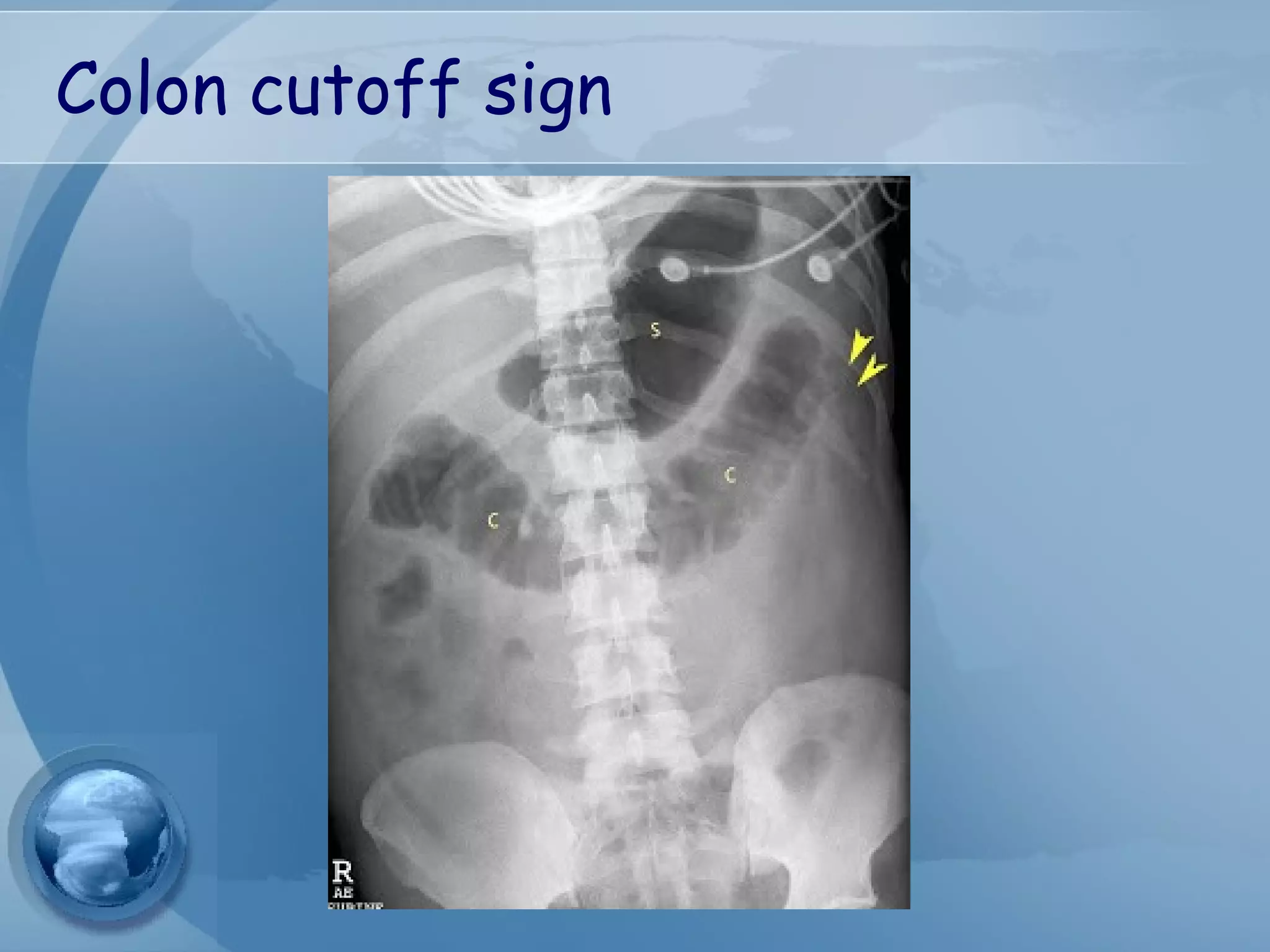

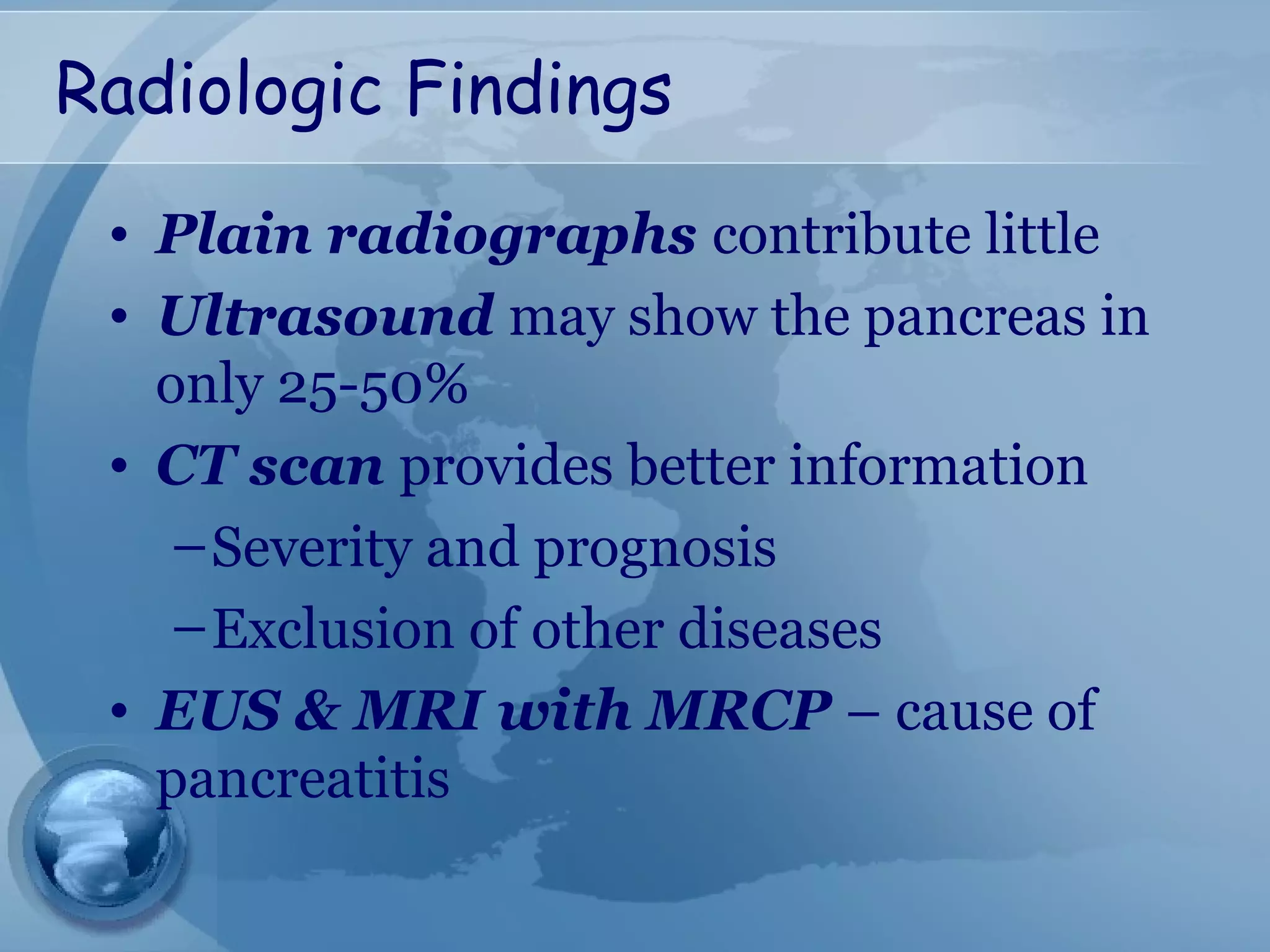

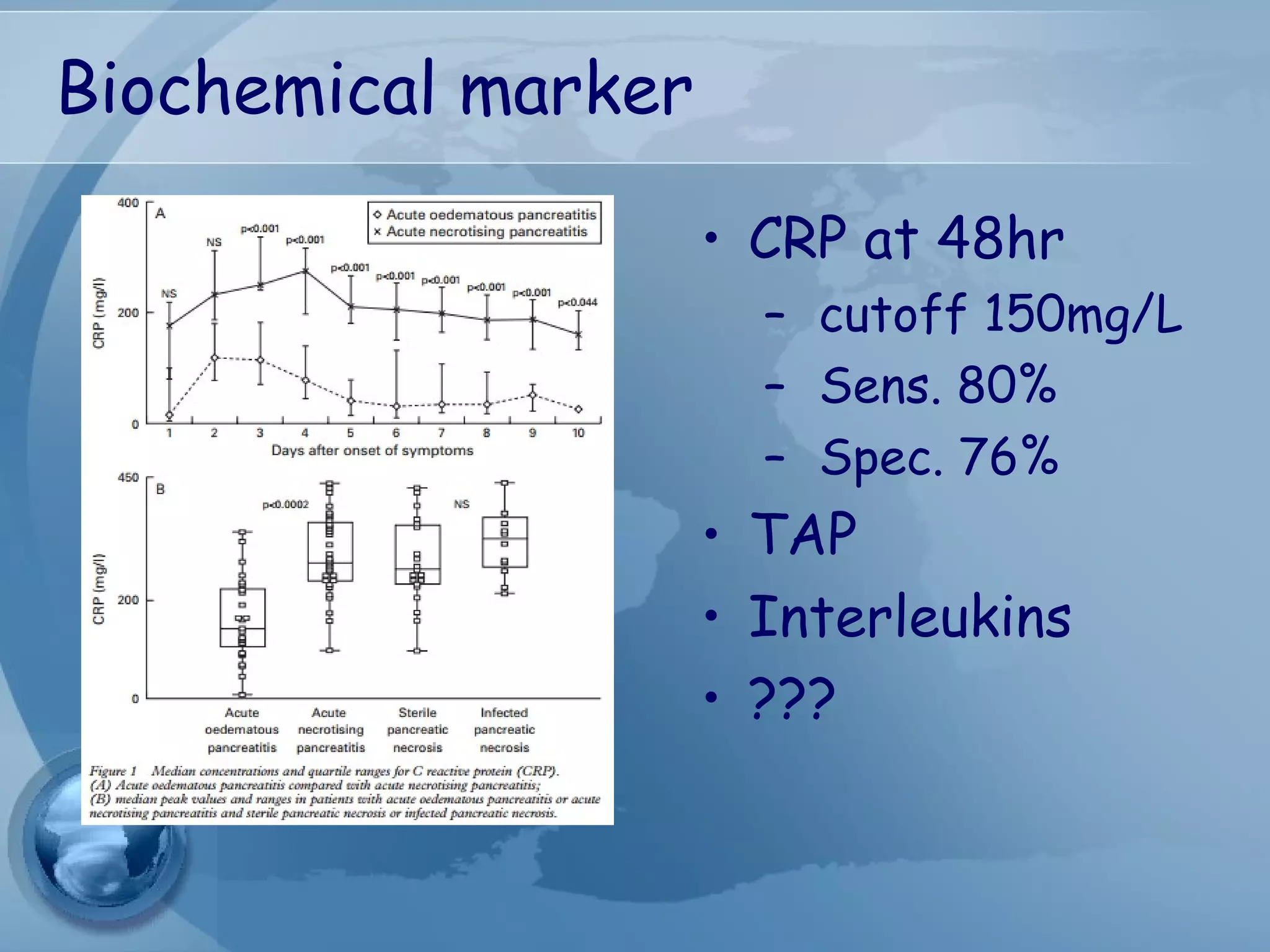

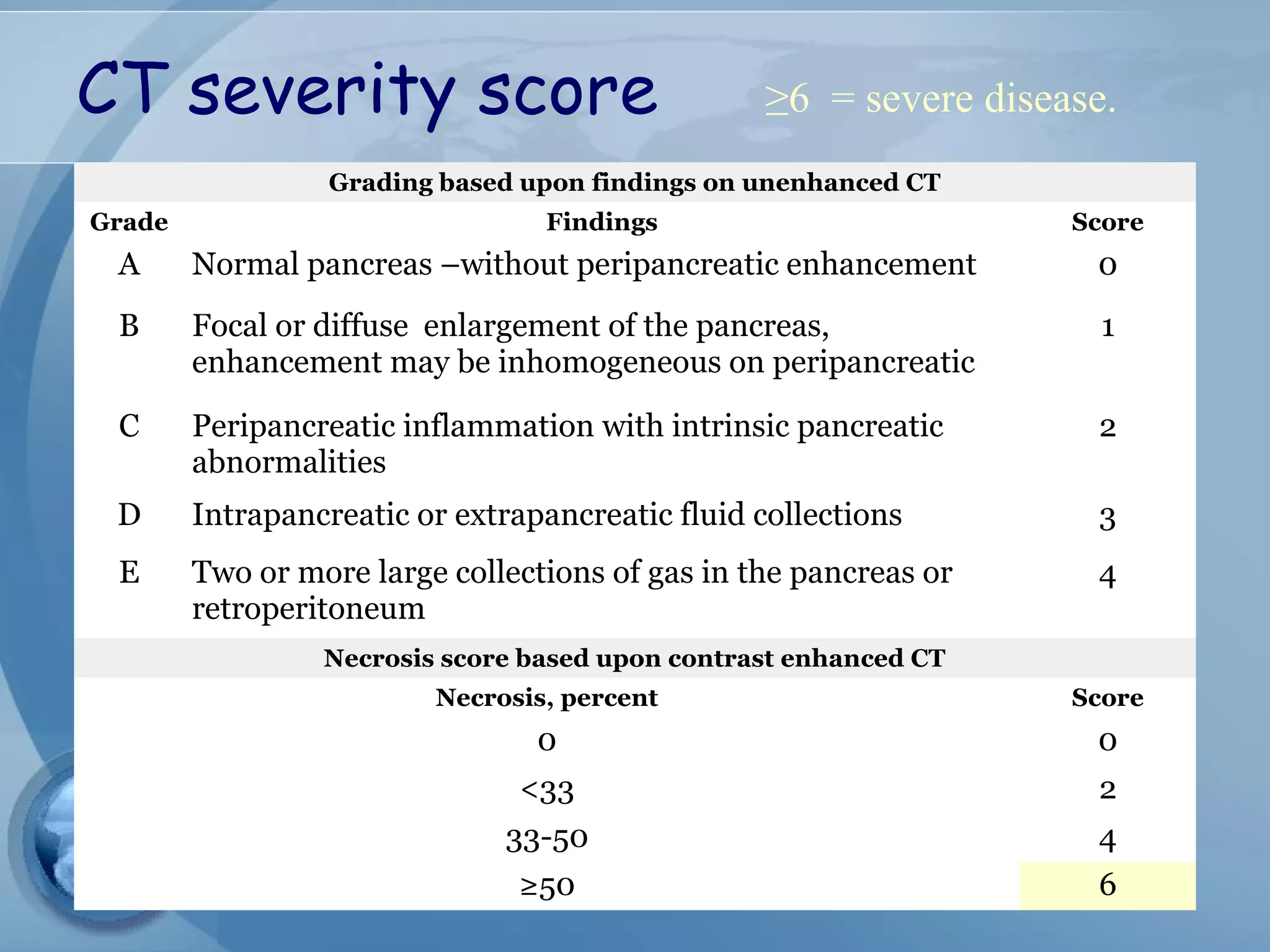

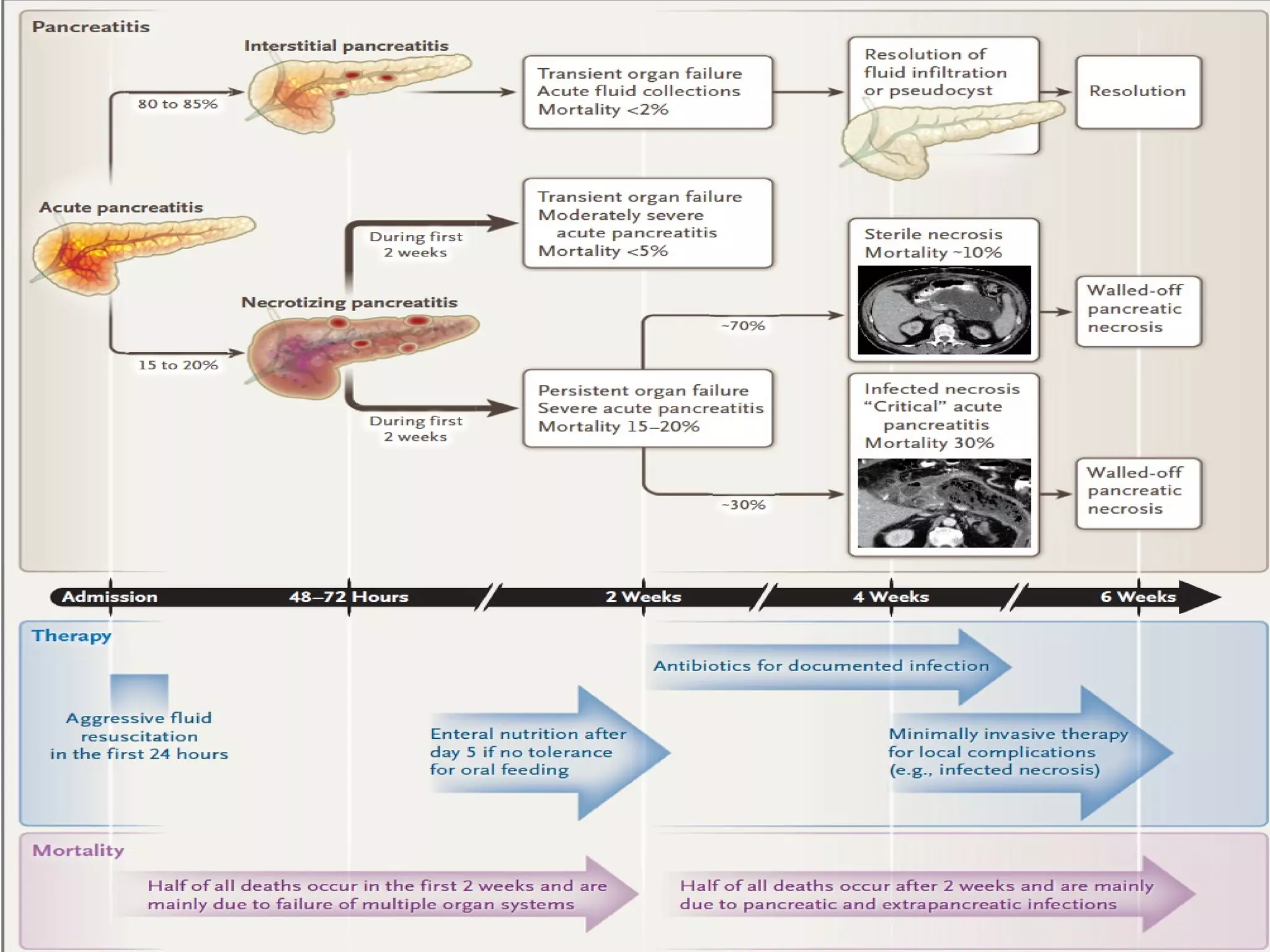

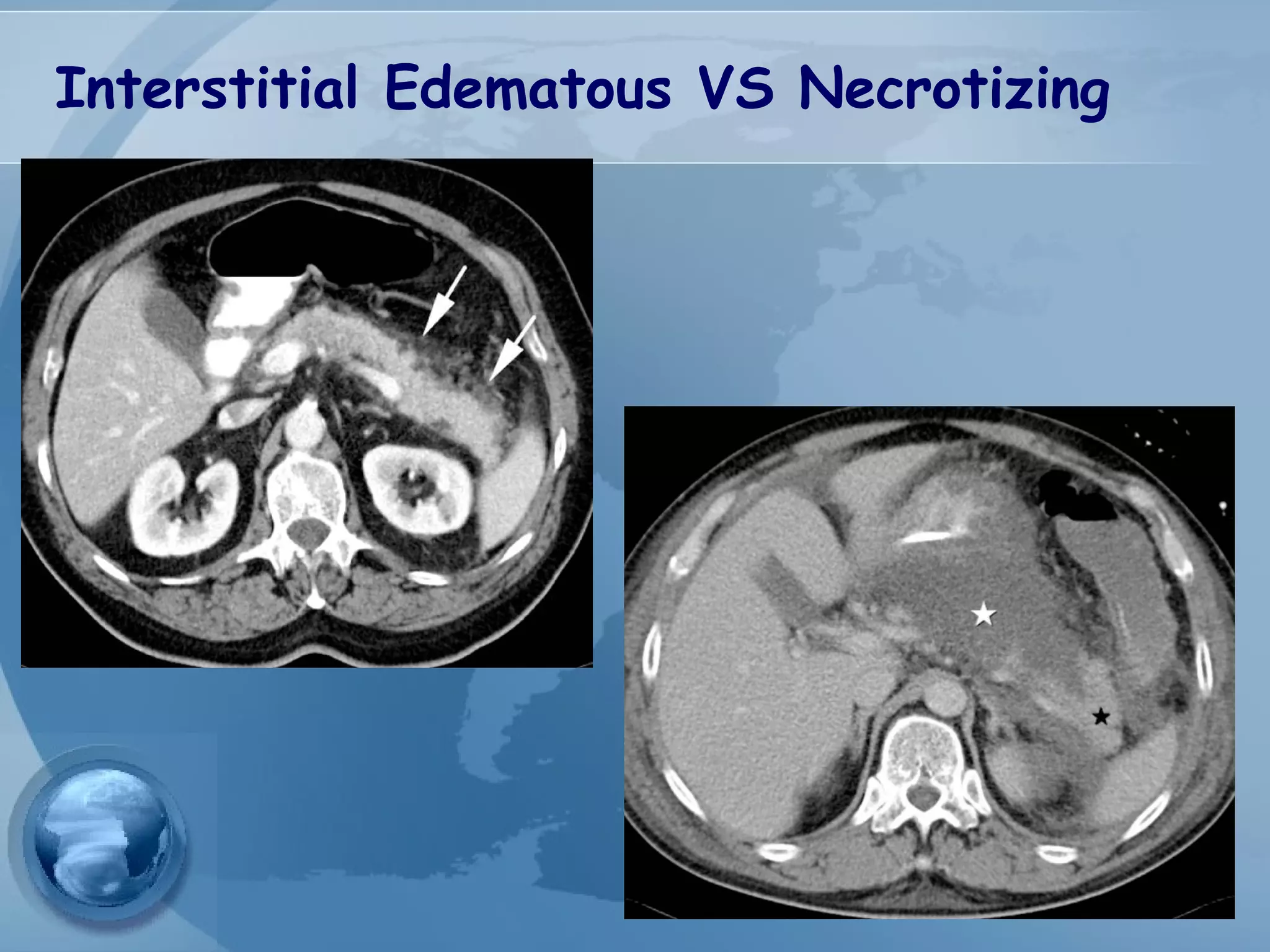

- Diagnosis requires abdominal pain consistent with pancreatitis plus serum lipase or amylase 3x upper limit and findings on imaging. CT scan is useful for assessing severity.

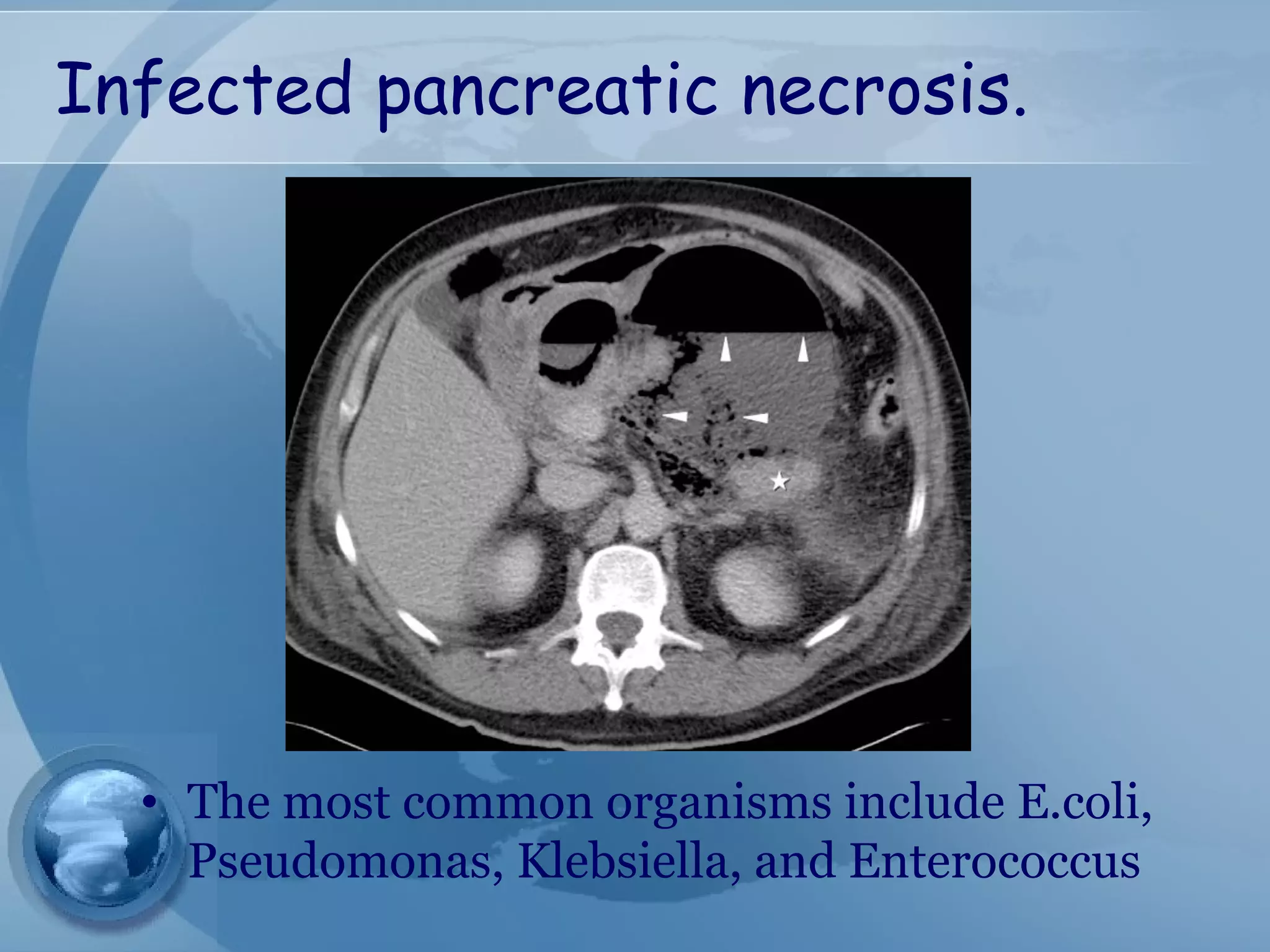

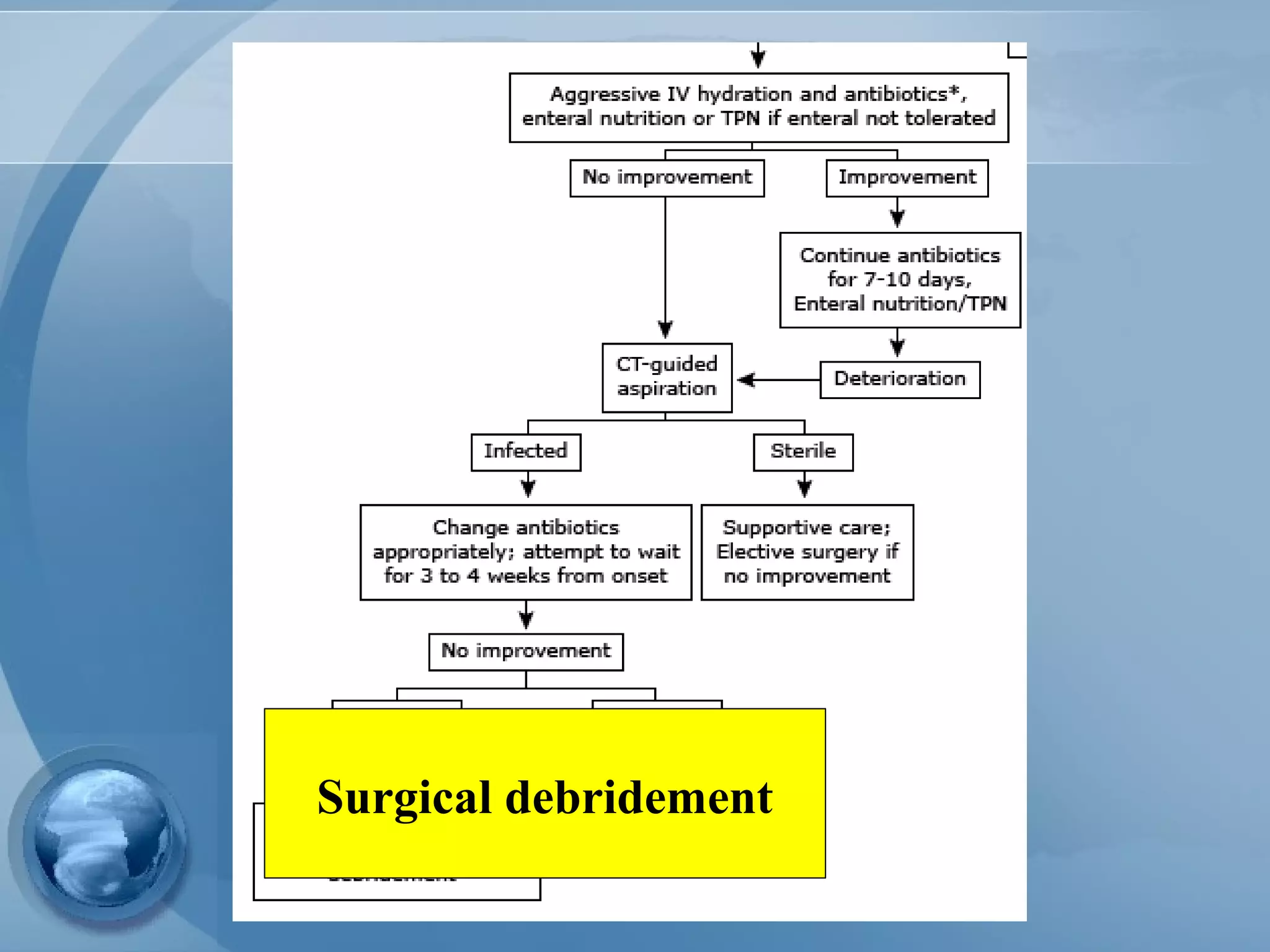

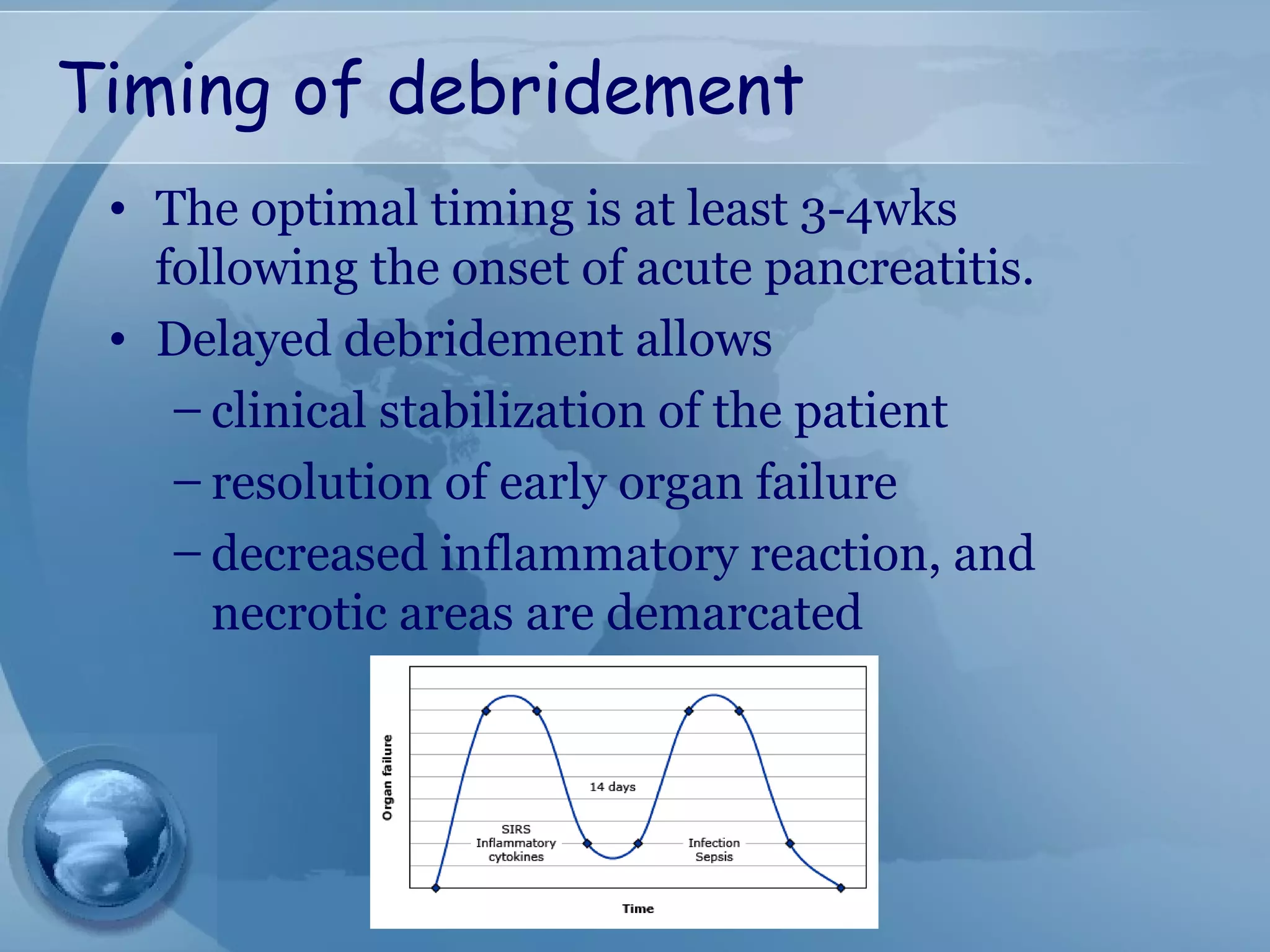

- Treatment involves aggressive IV fluids, monitoring for complications, enteral nutrition, and antibiotics only if infection is present. Severe cases may require endoscopic or minimally invasive drainage of pancreatic fluid and necrosis.

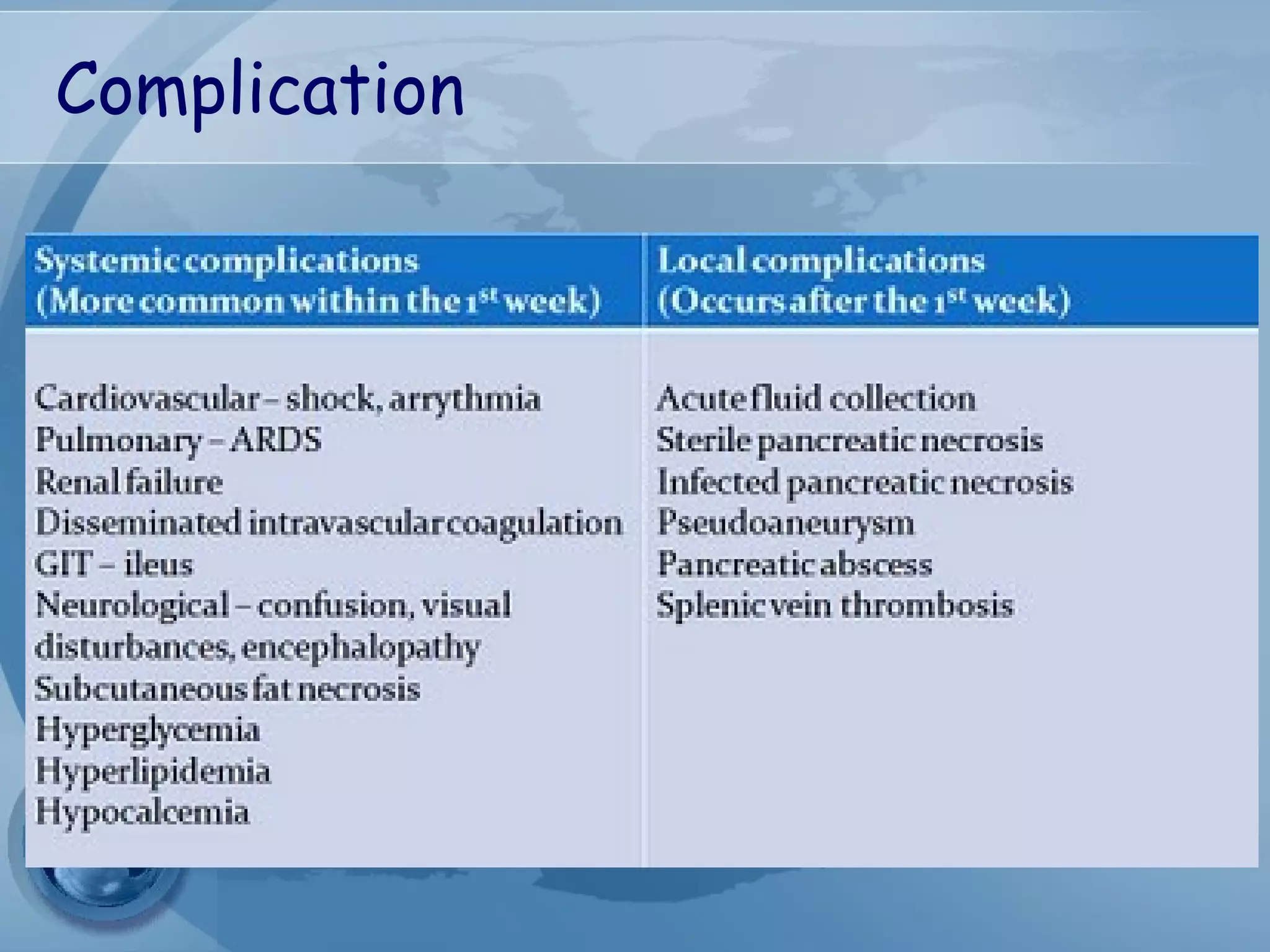

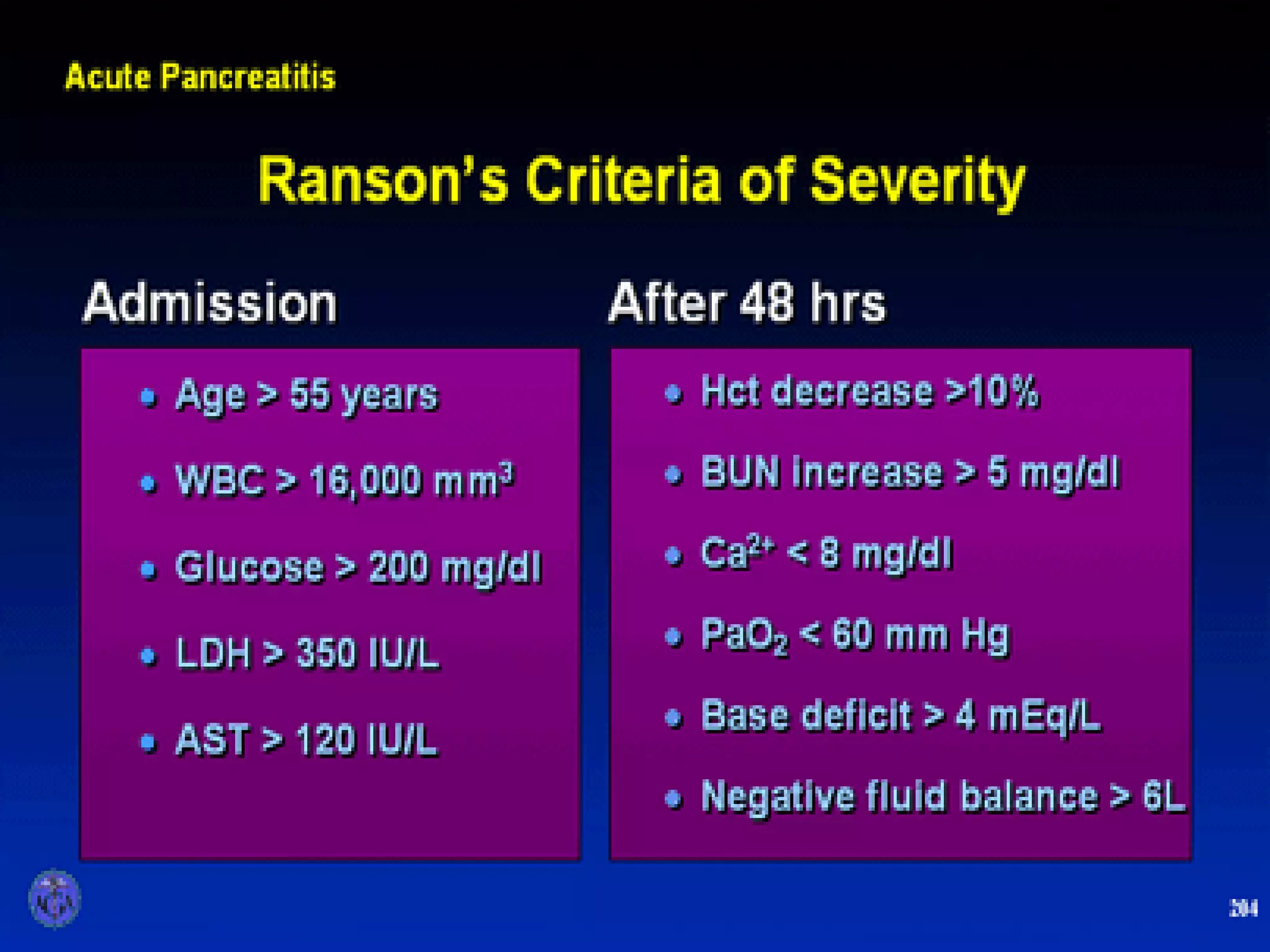

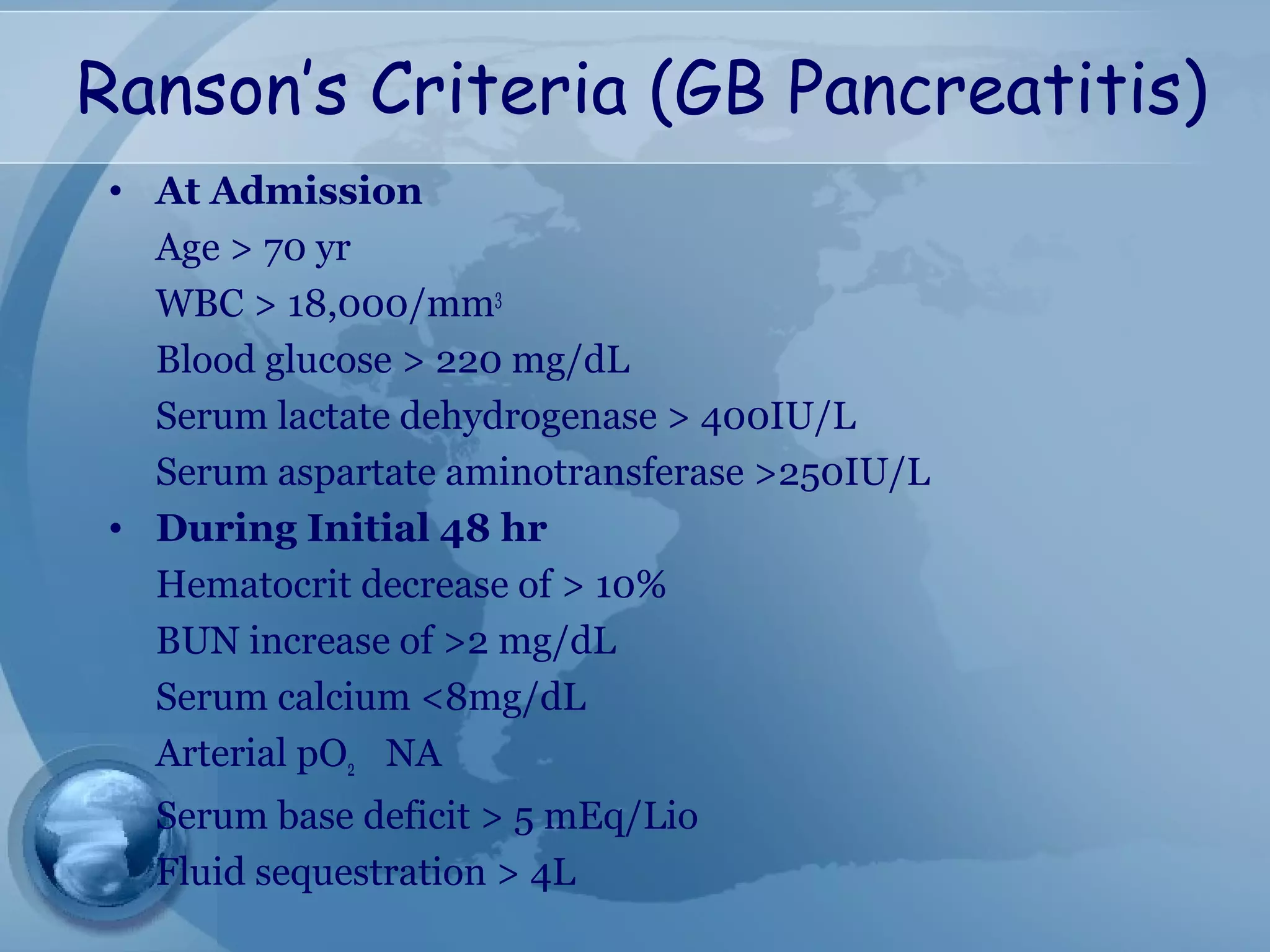

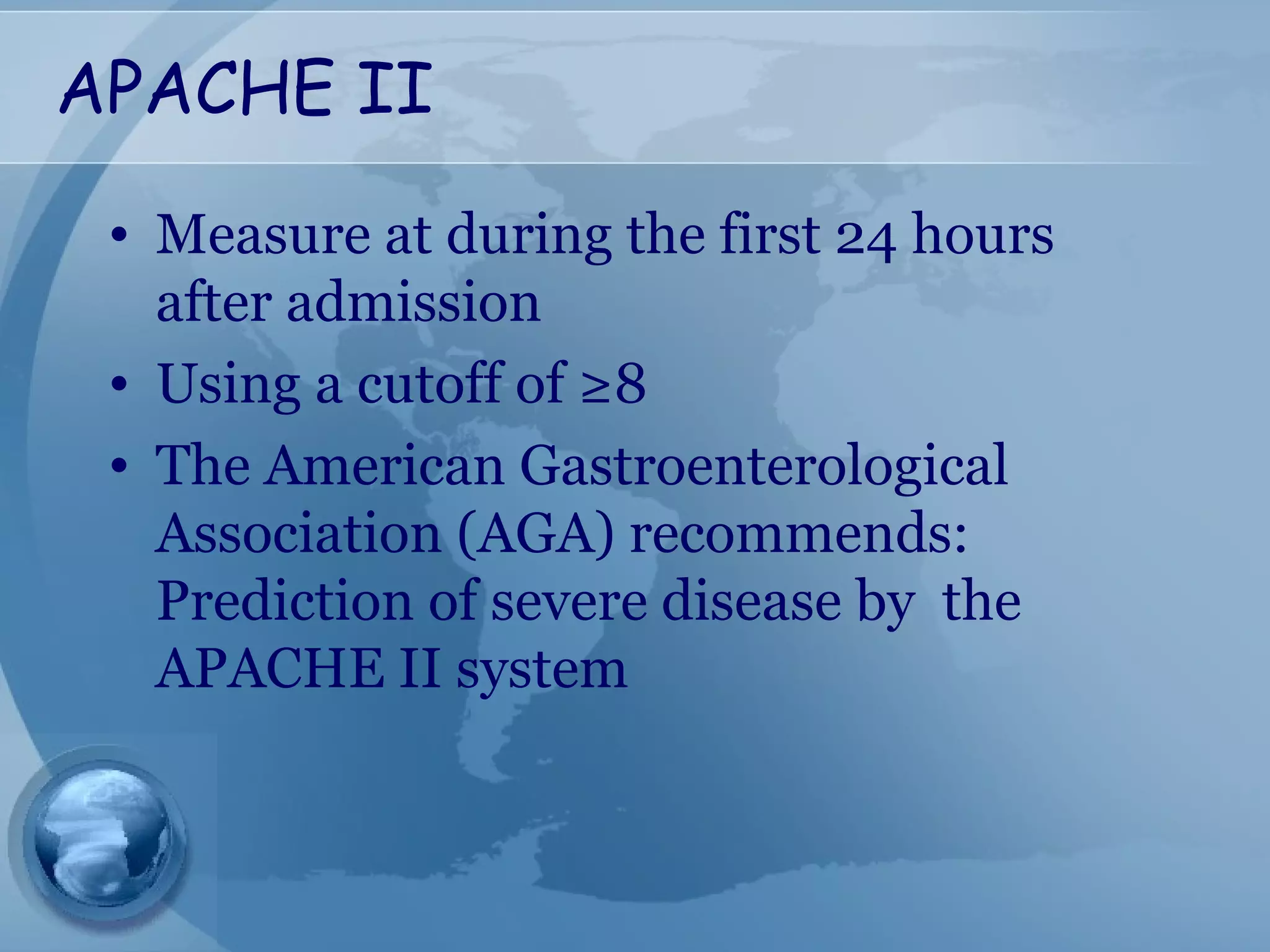

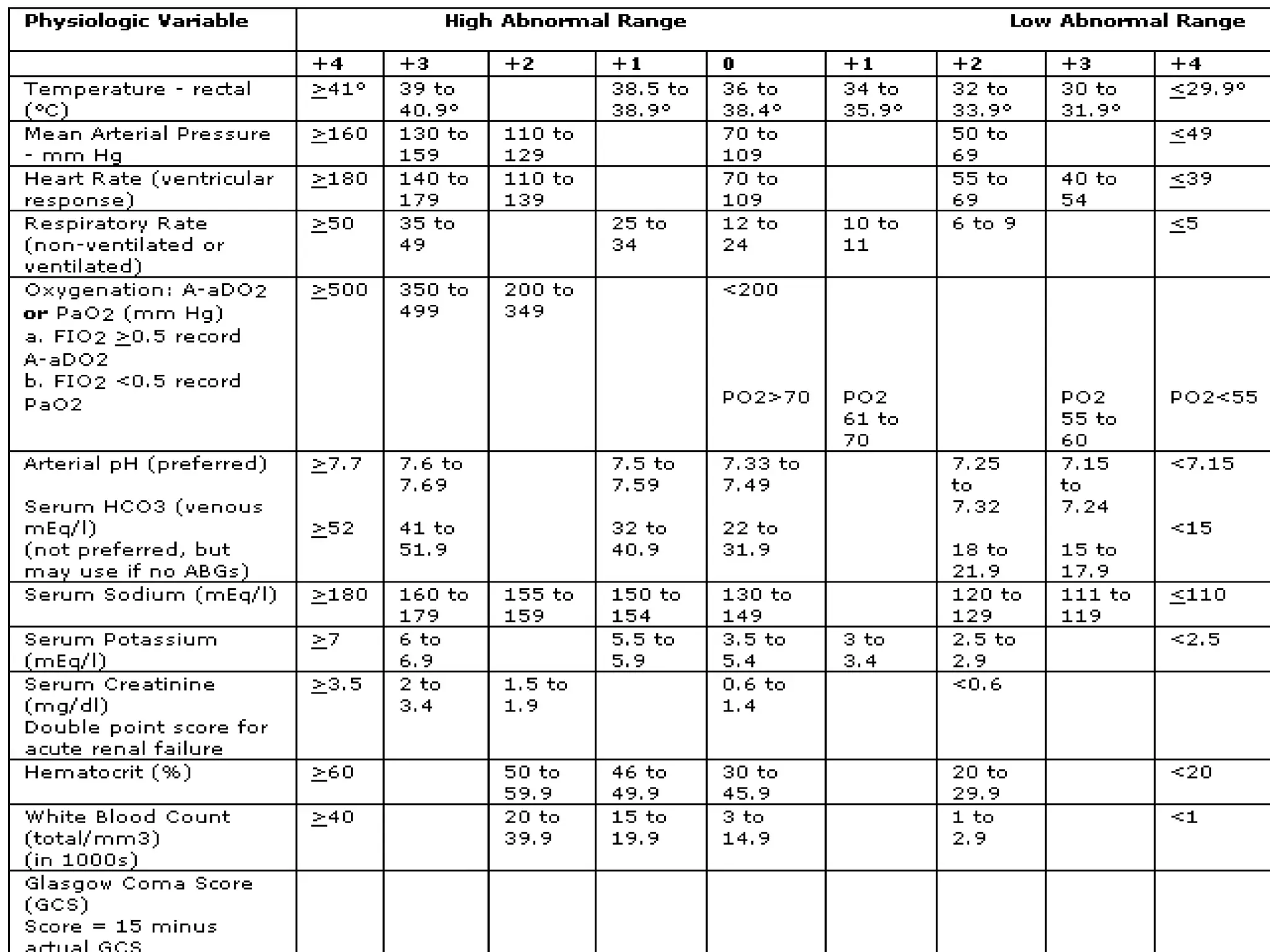

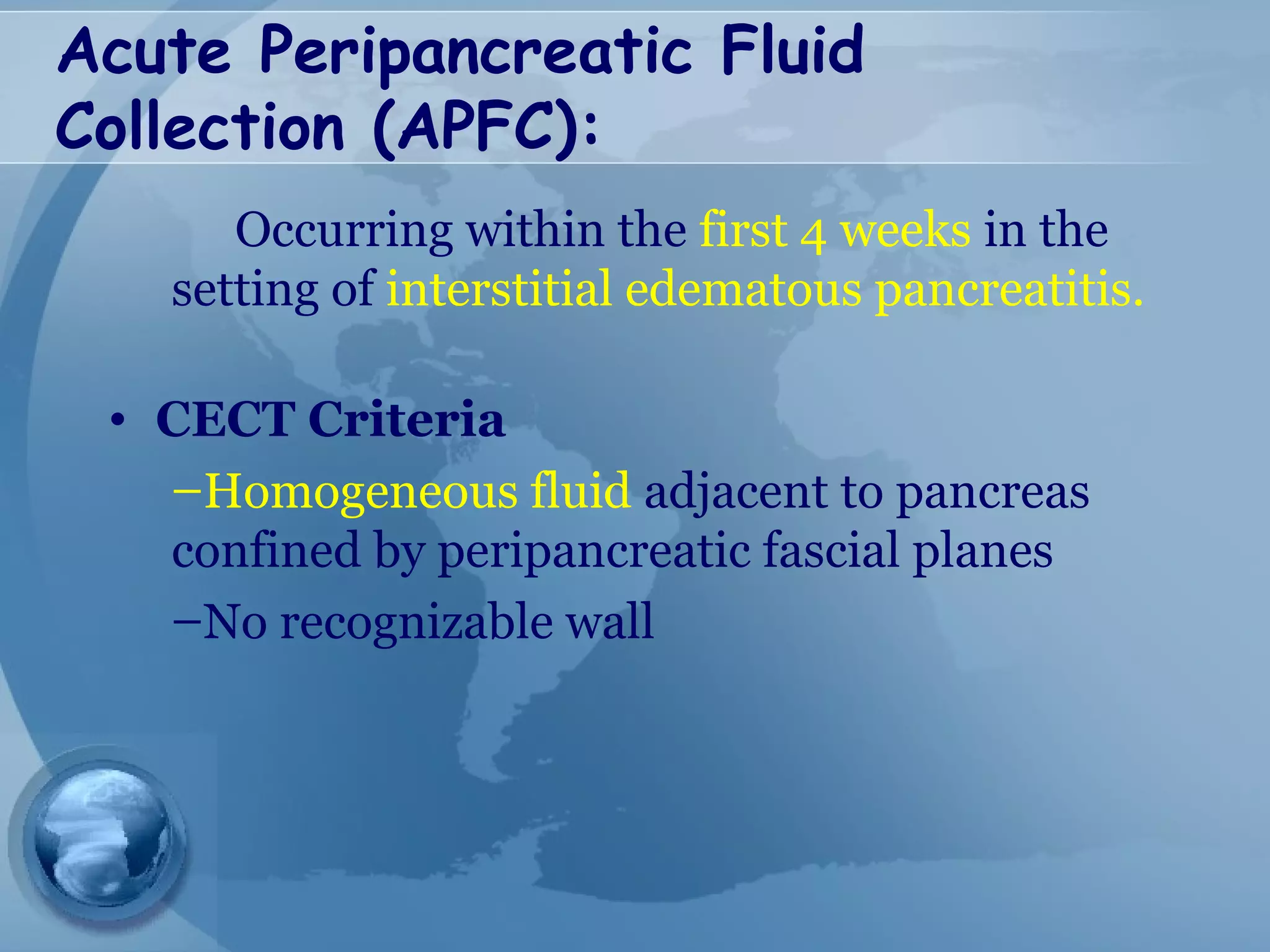

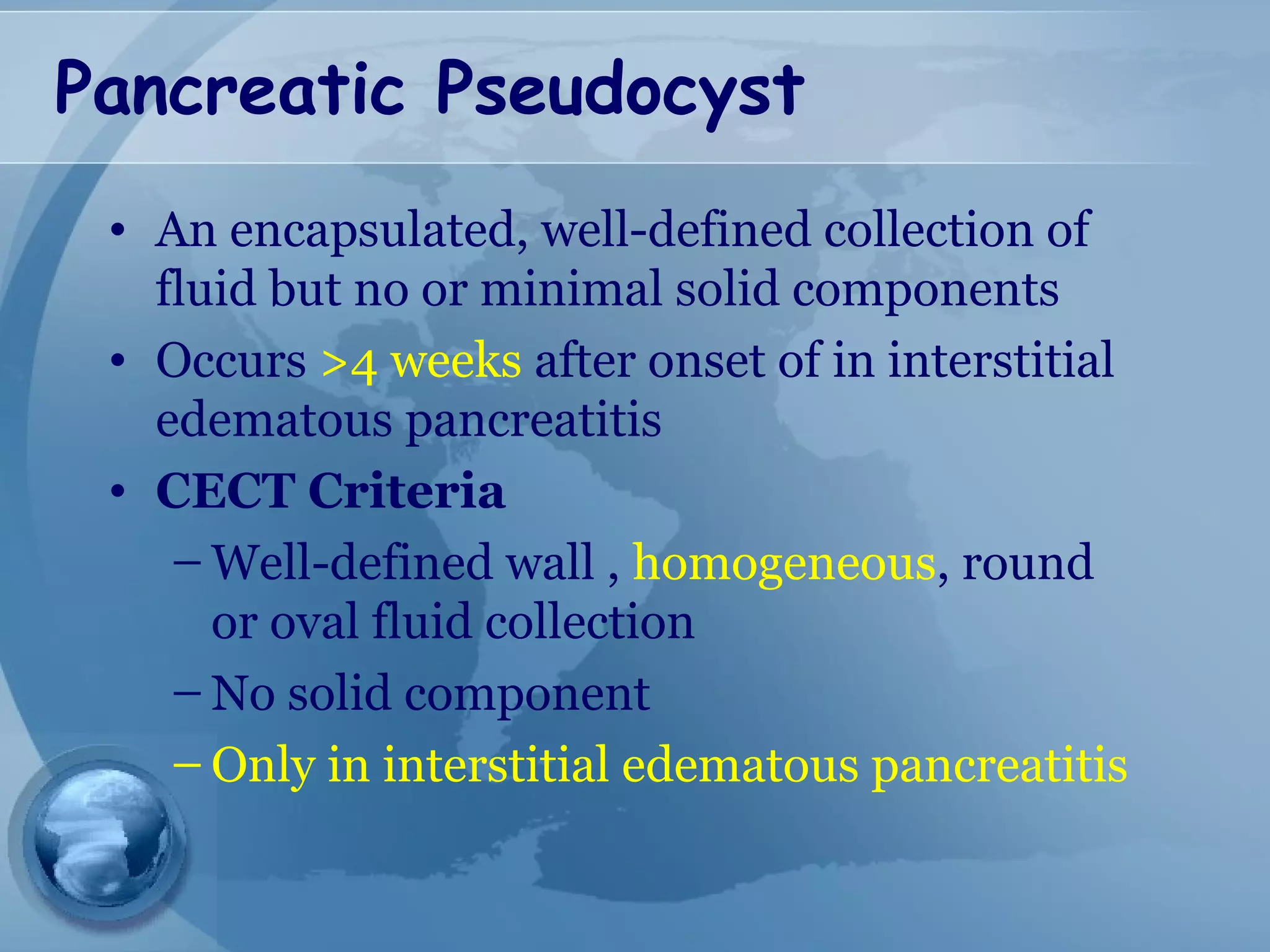

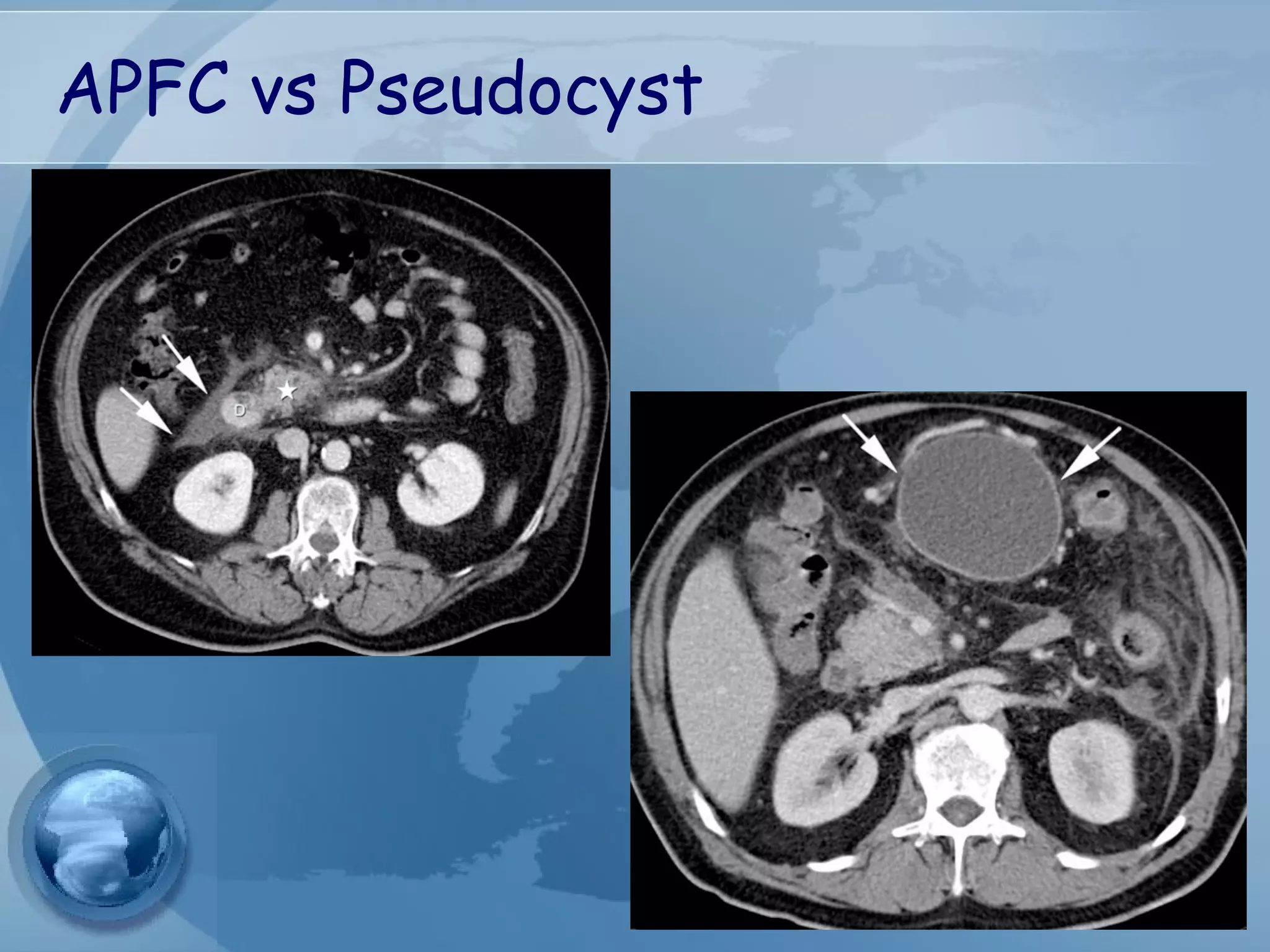

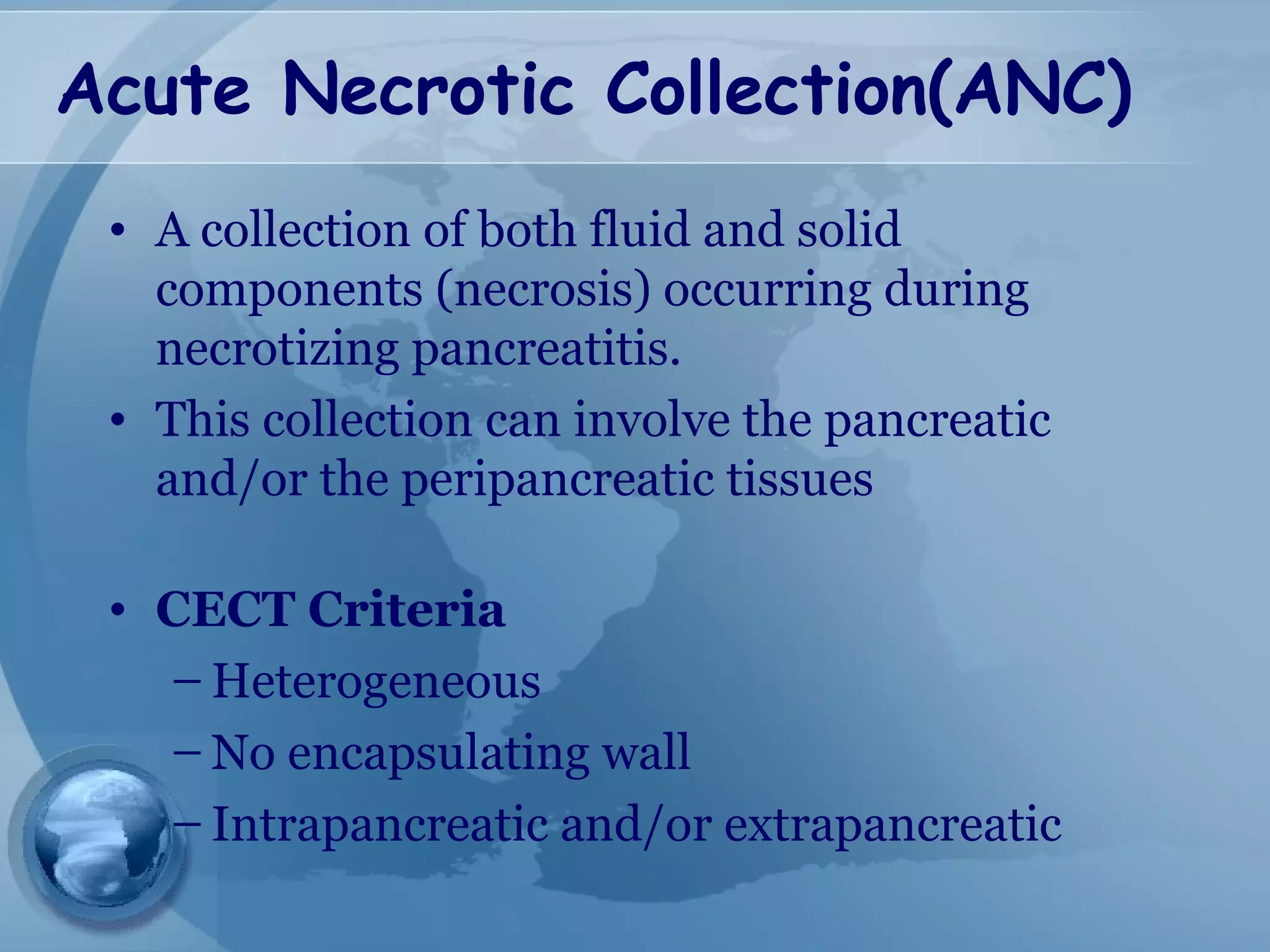

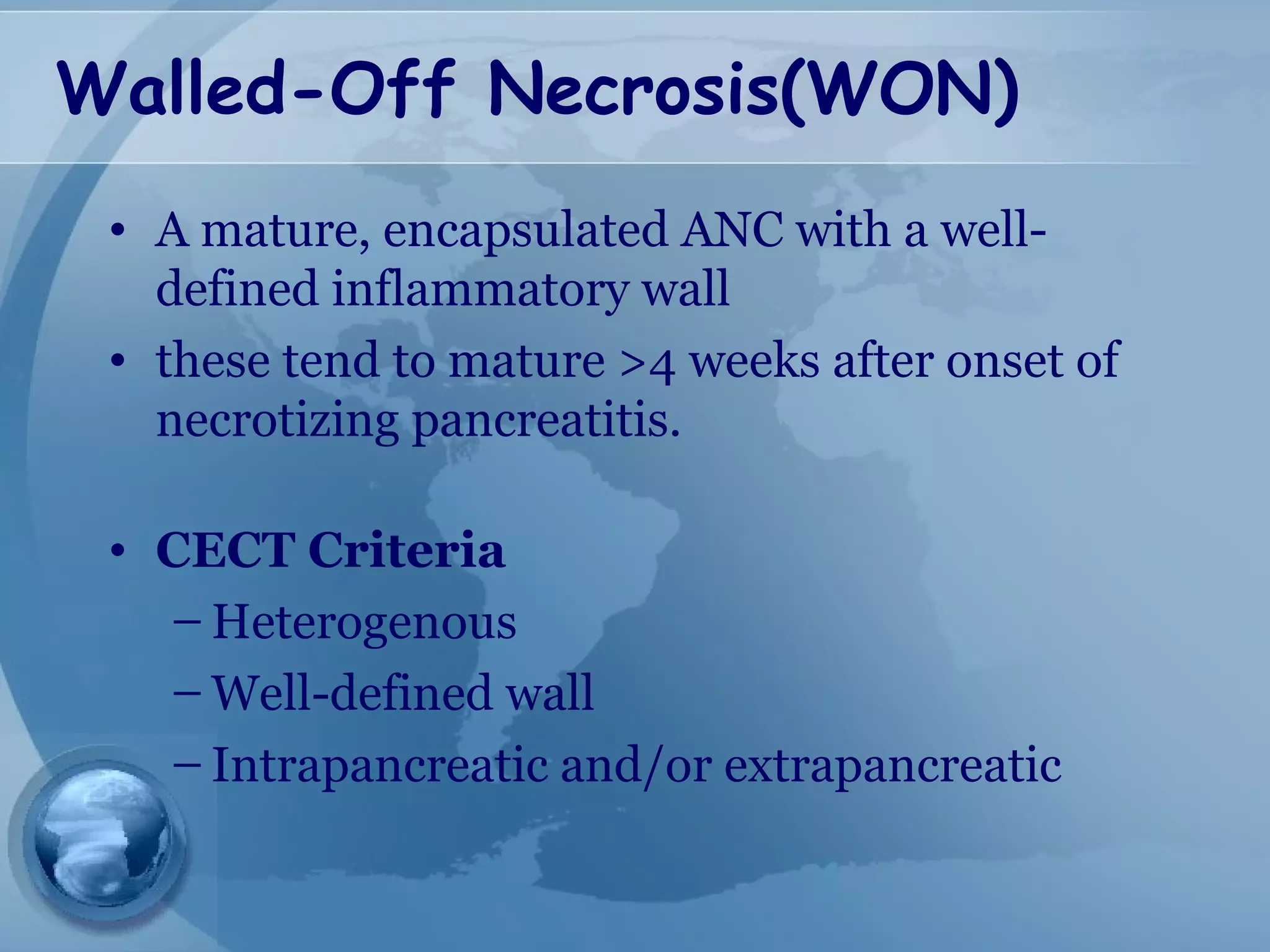

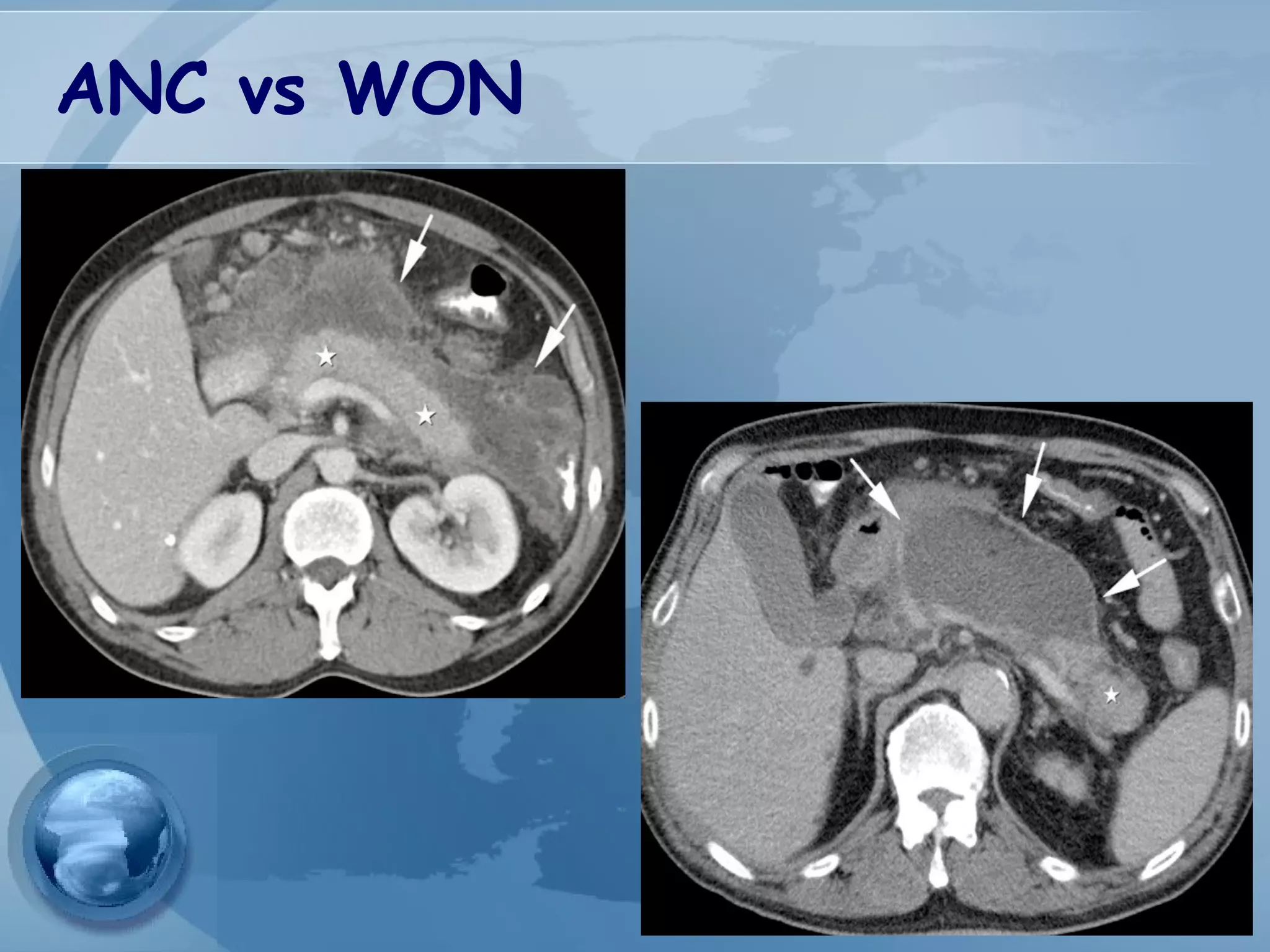

- Complications include pancreatic pseudocysts, abscesses, and sterile or infected pancreatic necrosis. Severity is classified based on organ failure