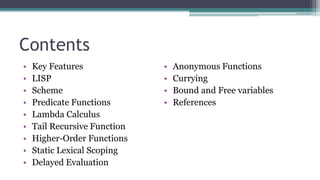

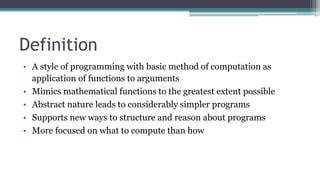

The document provides an overview of functional programming, including its key features, history, differences from imperative programming, and examples using Lisp and Scheme. Some of the main points covered include:

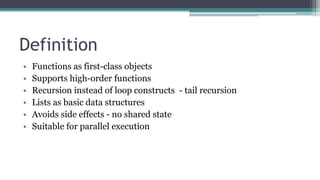

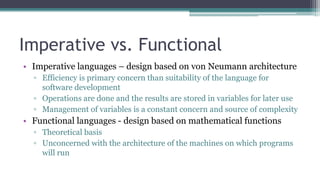

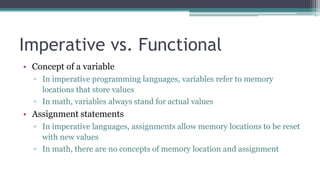

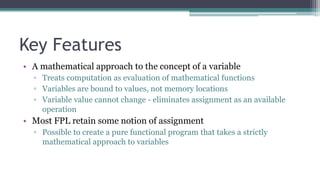

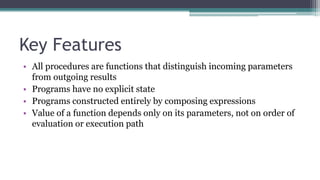

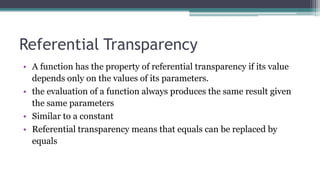

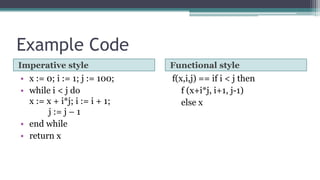

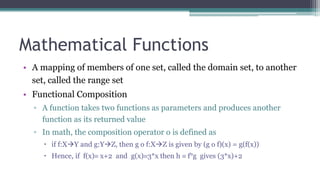

- Functional programming is based on evaluating mathematical functions rather than modifying state through assignments.

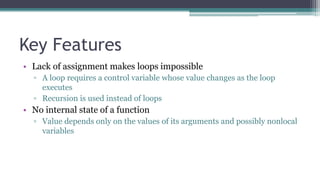

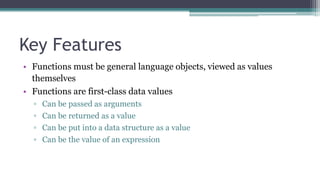

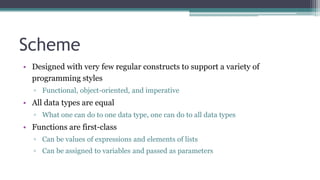

- It uses recursion instead of loops and treats functions as first-class objects.

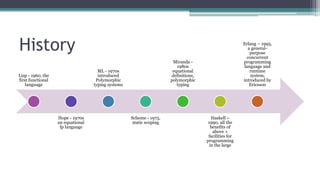

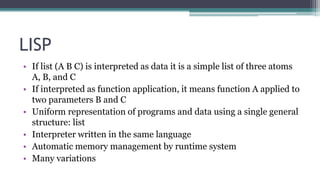

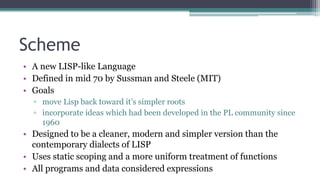

- Lisp was the first functional language in 1960 and introduced many core concepts like lists and first-class functions. Scheme was developed in 1975 as a simpler dialect of Lisp.

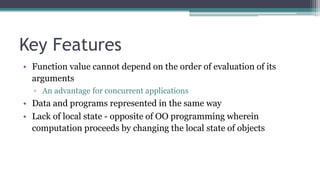

- Functional programs are more focused on what to compute rather than how to compute it, making them more modular and easier to reason about mathematically.

![Mathematical Functions

• Construction - A functional form that takes a list of functions as

parameters and yields a list of the results of applying each of its

parameter functions to a given parameter

Form: [f, g]

For f (x) x * x * x and g (x) x + 3,

[f, g] (4) yields (64, 7)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/funtionalprogrammingmaster-150830110643-lva1-app6891/85/Funtional-Programming-20-320.jpg)

![Anonymous Functions

• Written as lambda abstractions

• The function (x -> x * x) behaves exactly like sqr

▫ sqr x = x * x

▫ sqr 10 100

▫ (x -> x * x) 10 100

• Anonymous functions are first-class values

▫ map (x -> x * x) [1..10]

▫ [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/funtionalprogrammingmaster-150830110643-lva1-app6891/85/Funtional-Programming-66-320.jpg)

![References

1. “Conception, Evolution, and Application of Functional Programming Languages,” Paul Hudak,

ACM Computing Surveys 21/3, 1989, pp 359-411

2. “A Gentle Introduction to Haskell,” Paul Hudak and Joseph H. Fasel www.haskell.org/tutorial/

3. Report on the Programming Language Haskell 98 A Non-strict, Purely Functional Language,

Simon Peyton Jones and John Hughes [editors], February 1999 www.haskell.org

4. Real World Haskell, Bryan O'Sullivan, Don Stewart, and John Goerzen

book.realworldhaskell.org/read/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/funtionalprogrammingmaster-150830110643-lva1-app6891/85/Funtional-Programming-71-320.jpg)