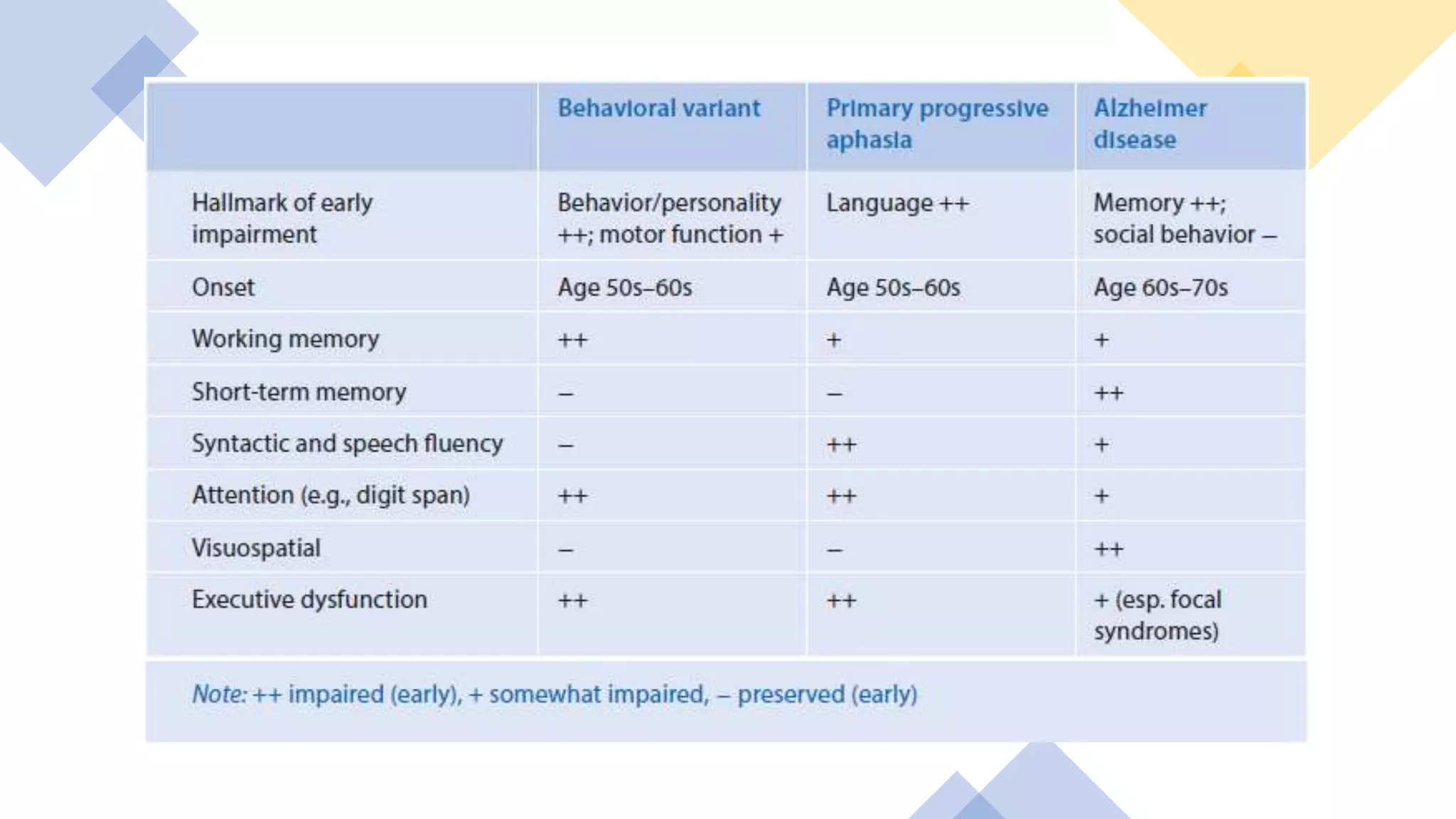

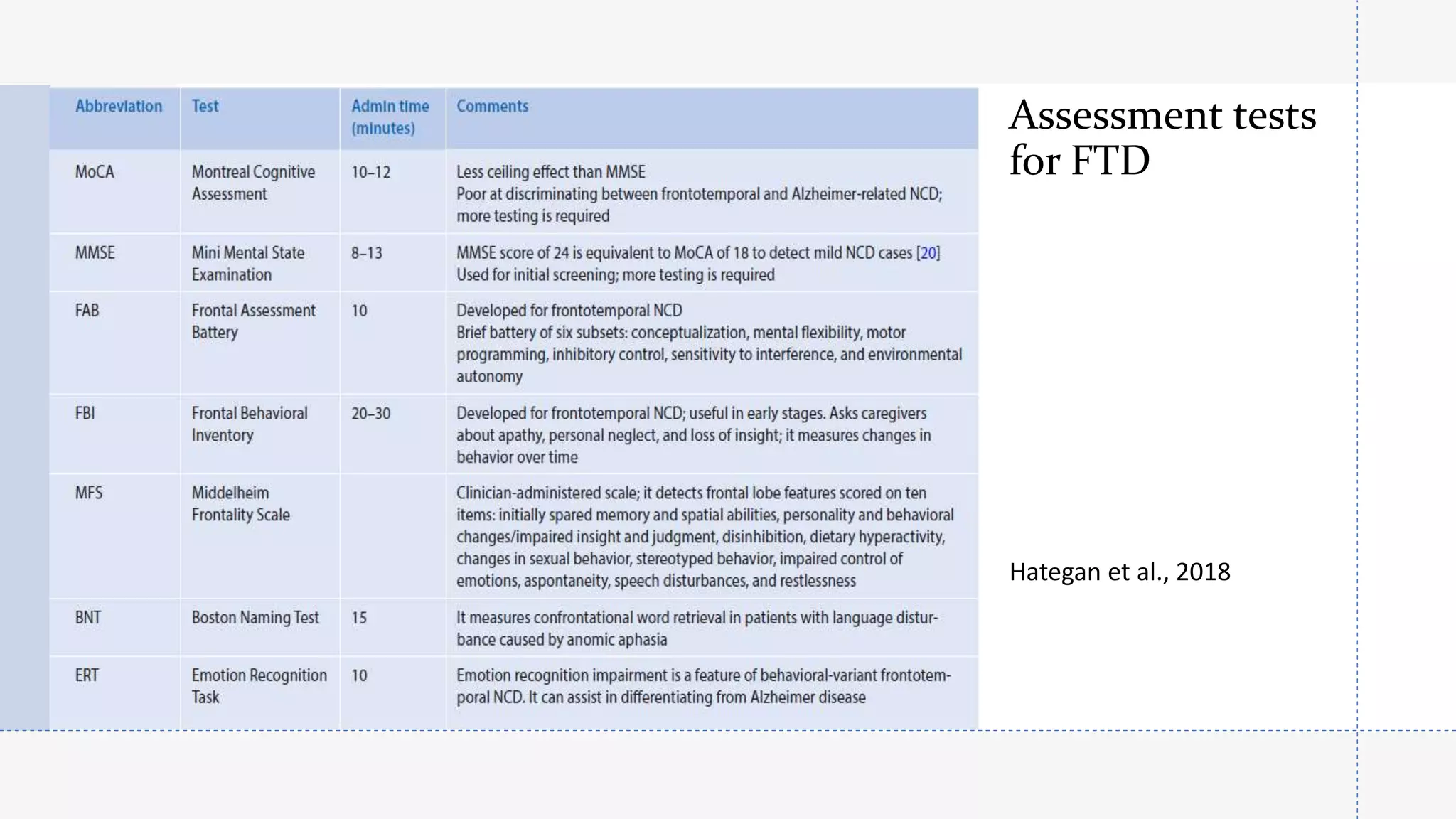

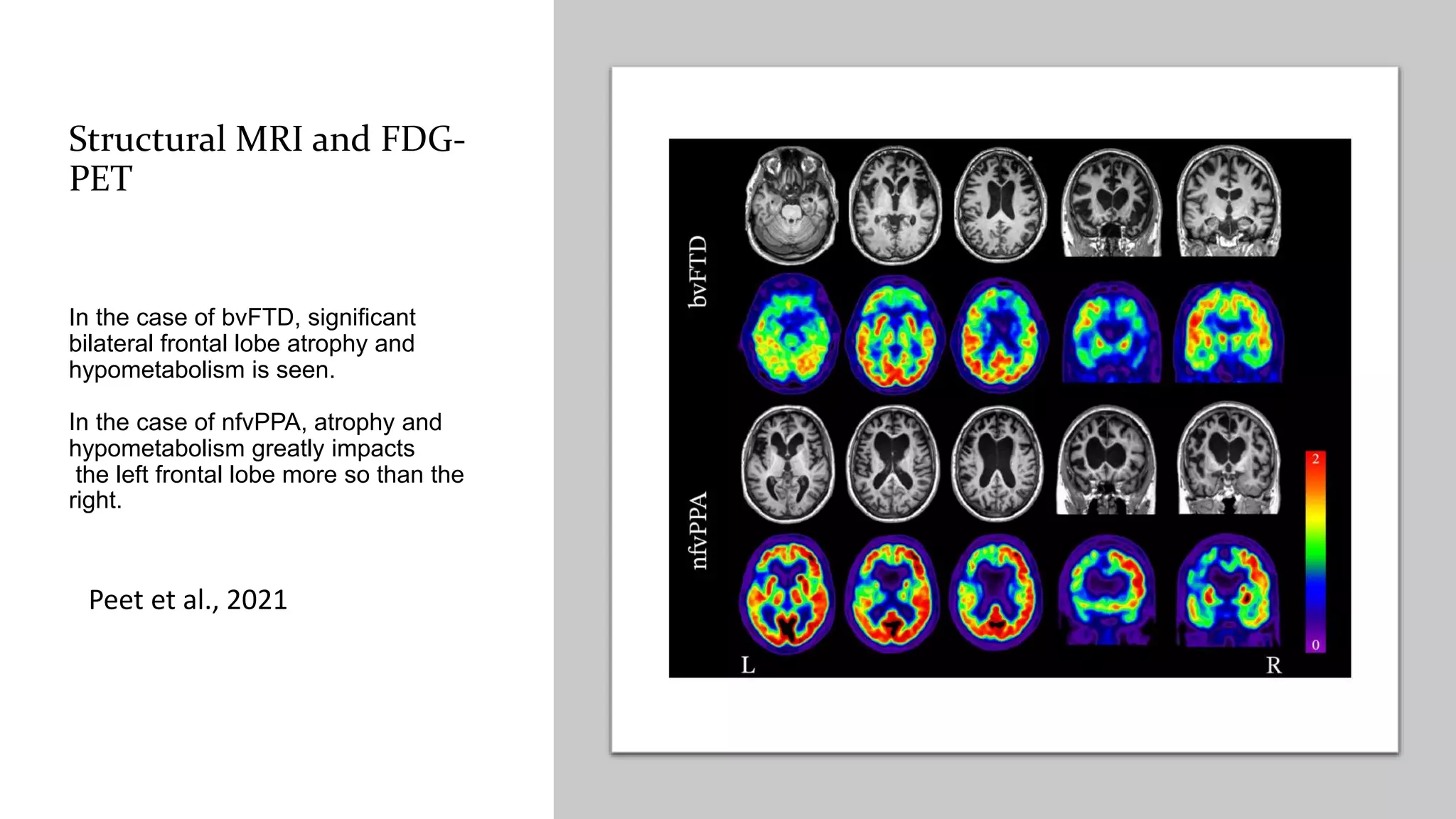

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the second most common early-onset dementia. There are several variants of FTD including behavioral variant FTD and primary progressive aphasias like semantic dementia and progressive nonfluent aphasia. Genetic causes include mutations in MAPT, GRN, and C9ORF72 genes. Neuroimaging shows characteristic patterns of frontal and temporal lobe atrophy depending on the variant. Biomarkers like increased blood GFAP levels may help with diagnosis. Currently, there are no approved disease-modifying treatments, but some medications may help treat symptoms. Research focuses on new targets like gene therapy to potentially slow progression in the future.

![Semantic dementia [semantic variant of primary

progressive aphasia (svPPA)]

Affects knowledge of the meaning of words (Familiar) for

example in a menu (“What is spaghetti?”) pathognomonic of

semantic dementia (affection of dominant temporal lobe).

Speech is fluent with preserved grammar but empty,

circumlocutory with early prominent difficulty retrieving names

Impaired comprehension of single word meanings

Early in the disease, the semantic deficit may be well

compensated and discovered with detailed assessment](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/frontotemporaldementia-211220133747/75/Frontotemporal-dementia-15-2048.jpg)

![With disease progression, semantic impairment

also affects visual information [impaired

recognition of familiar faces (prosopagnosia)]

/or recognition of visual objects (visual agnosia)

due to spread to posterior temporal structures

and nondominant pole]

Impaired recognition of odours and flavours,

and behavioural disturbances develop late in

the disease (due to spread to the right anterior

temporal lobe)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/frontotemporaldementia-211220133747/75/Frontotemporal-dementia-16-2048.jpg)

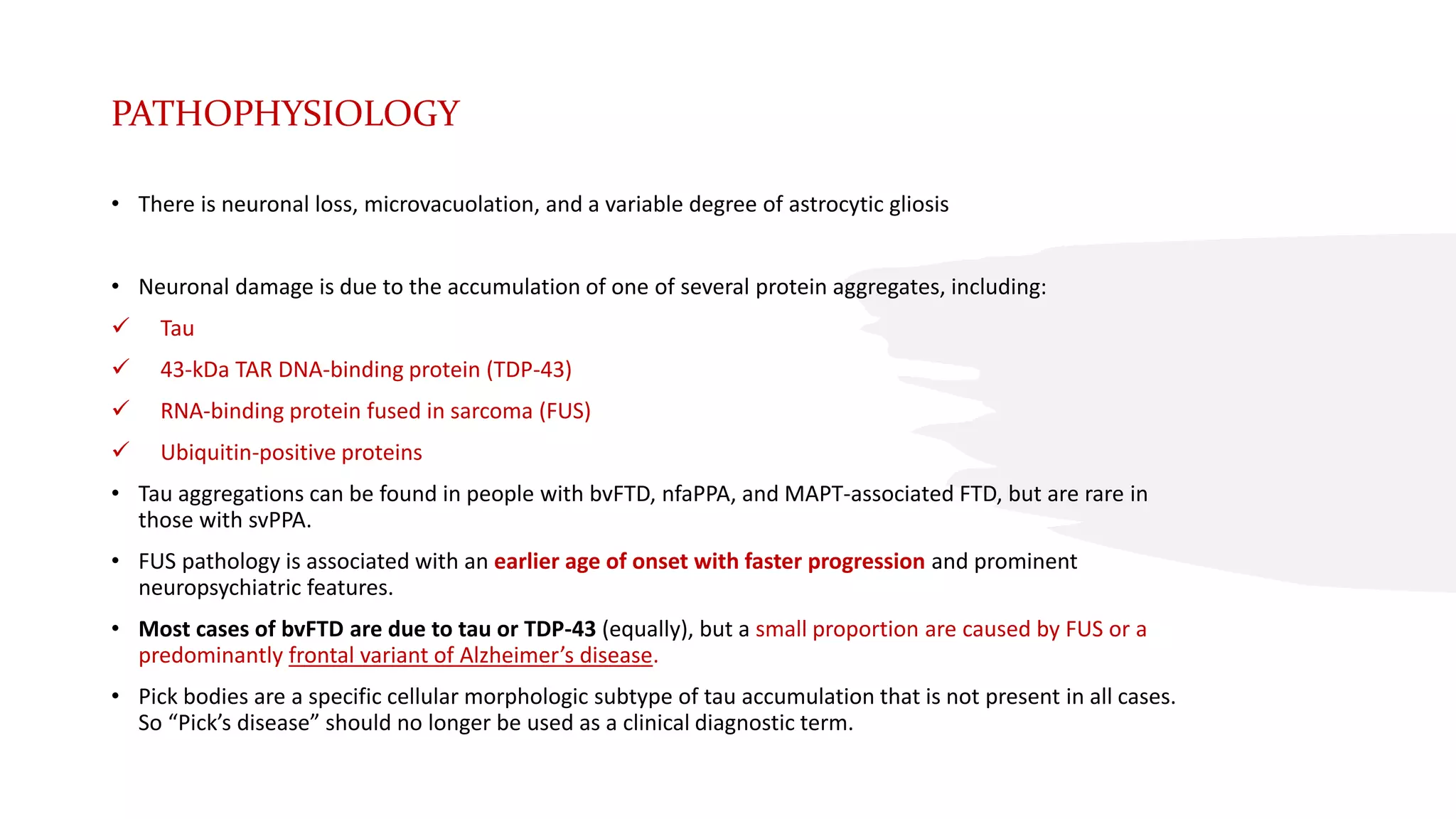

![[18 F]-FDG-PET in bvFTD:

right fronto (temporal)

hypometabolism

SPECT study of a patient suffering from FTD. Transaxial slices

from bottom to top . Moderate to severe cortical hypoperfusion

of the frontal lobes, especially on the left , and slight

hypoperfusion of the temporal poles

Dierckx et al., 2014

According to NICE guidelines, 2018

If the diagnosis is uncertain and frontotemporal dementia is suspected, use either: FDG-PET or perfusion

SPECT.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/frontotemporaldementia-211220133747/75/Frontotemporal-dementia-38-2048.jpg)

![• Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ, Furst AJ, Ogar JM, Racine CA, Mormino EC et al (2008) Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary

progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 64(4):388–401.

• Dubois, B. ; Litvan, I.; The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 55(11): 1621-1626, 2000.

• Modinos G, Obiols JE, Pousa E, Vicens J. Theory of Mind in different dementia profiles. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009 Winter;21(1):100-1. doi:

10.1176/jnp.2009.21.1.100. PMID: 19359462.

• Garcin B, Urbanski M, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Levy R and Volle E (2018) Anterior Temporal Lobe Morphometry Predicts Categorization Ability. Front.

Hum. Neurosci. 12:36. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00036

• Slachevsky, A; Dubois, B. Frontal Assessment Battery and Differential Diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer Disease. Archives of

Neurology. 61(7): 1104-1107, 2004.

• Kertesz, A., Davidson, W., & Fox, H. (1997). Frontal behavioral inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. The Canadian journal of

neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques, 24 1, 29-36 .

• Katisko K, Cajanus A, Huber Net al, GFAP as a biomarker in frontotemporal dementia and primary psychiatric disorders: diagnostic and prognostic

performance, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2021;92:1305-1312.

• Hategan A, Bourgeois JA, Hirsch CH, Giroux C. Geriatric Psychiatry; A Case-Based Textbook. Springer, Cham, Springer International Publishing AG, part

of Springer Nature 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67555-8.

• Dierckx RAJO, Otte A, de Vries EFJ, van Waarde A, Leenders KL. PET and SPECT in Neurology. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014.

• Peet BT , Spina S ,Mundada N , La Joie R. Neuroimaging in Frontotemporal Dementia: Heterogeneity and Relationships with Underlying

Neuropathology. Neurotherapeutics (2021) 18:728–752.

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers

NICE guideline [NG97] Published date: June 2018.

• Butterworth S, Drugs and Therapeutics Committee. Guidelines for the Pharmacological Management of Dementia, HPFT Guideline. Published date:

September 2020.

• Li, P., Quan, W., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Liu, S."Efficacy of memantine on neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with the severity of behavioral

variant frontotemporal dementia: A six-month, open-label, self-controlled clinical trial". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 12.1 (2016): 492-498.

• Kishi T, Matsunaga S, Iwata N. Memantine for the treatment of frontotemporal dementia: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2883-

2885.https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S94430.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/frontotemporaldementia-211220133747/75/Frontotemporal-dementia-47-2048.jpg)