In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the application of near-surface mounted fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) reinforcement in reinforced concrete structures. Nevertheless, there is a discernible disparity in the accessibility of accurate and customize measures for augmenting flexural strength through the use of near-surface mounted (NSM) reinforcement techniques. Although several basic models have been proposed to predict the flexural capacity achievable with this technology, established codes have not yet provided mathematical equations for this specific purpose. This study presents two separate methodologies with the objective of enhancing the development of suitable code provisions. In the first stage, A comprehensive and reliable database has been developed to leverage the predictive accuracy of neural networks in the computation of the flexural capacity of reinforced beams that utilize near-surface mounted reinforcement. Following this, the results obtained from the neural network are employed to construct a linear equation using the group method of data handling (GMDH) technique. The presented equation has been carefully formulated to produce a concise and simple mathematical expression that enables the determination of the flexural strength of a beam on the field. The evaluation of the accuracy and effectiveness of both the neural network and the suggested equation is conducted in accordance with the requirements specified in ACI 440.R2 for externally bonded reinforcements. The neural network's prediction has a mean absolute error of just 5% in comparison to the experimental results and the GMDH equations exhibit a noteworthy level of concurrence with the experimental outcomes, as they display a mean absolute error of 16%.

![2 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

1. Introduction

The application of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) reinforcement using the near surface mounted

(NSM) technology has been increasingly prominent in enhancing the strength of reinforced

concrete (RC) elements. The proposed methodology entails the creation of slots within the

concrete cover, followed by the infusion of epoxy as a bonding agent, prior to the installation of

the FRP reinforcement. Several research conducted over the past two decades have examined

and contrasted the effectiveness of this strategy in relation to the externally bonded (EB)

approach. The process of designing externally bonded FRP has been simplified due to the efforts

of many international organizations, such as the American Concrete Institute (ACI) 440.2R-17

[1]. Nevertheless, according to research findings, de-bonding takes place at a low level of tension

between the FRP and concrete surface, despite the broad use of the EB FRP approach. Therefore,

this technique does not allow for the complete realization of the entire potential of FRP [2]. The

advantages of the novel technology in comparison to the preceding (EB) method encompass

enhanced safeguarding, a superior bond, heightened aesthetic appeal, improved surface

preparation, and the possibility of securing attachment to adjacent components [3]. The

enhancement of bond performance, in comparison to EB systems, is a crucial element in the

construction of NSM-FRP systems [4]. Several elements linked to FRP, including the size of the

bars, surface treatment, groove geometry, concrete properties, and adhesive used in the test setup,

have been found to affect the bond between concrete and NSM FRP bars [5,6]. Over the course

of the last ten years, there have been notable advancements in the near surface mounted

technique, including the development of novel anchorage methods [7], and the utilization of

cost-effective materials for manufacturing FRP bars at building sites [8]. The application of FRP

systems to reinforce a bridge slab in the negative moment zone was first observed in northern

Sweden during the 1940s, as documented by Asplund in 1949, in this particular process, the steel

rods were incorporated into the concrete cover using cement mortar [9]. Four slabs were

subjected to experimental reinforcement using an identical technique prior to the commencement

of the strengthening procedure. Subsequently, these slabs were subjected to loading until failure

occurred. In March 1949, an experiment was conducted where approximately 600 meters of steel

bars were successfully bonded to the concrete cover. The results of this experiment provided

evidence of the efficacy of this strategy. It is important to acknowledge that the establishment of

a successful concrete cover bond in these projects presents a complex undertaking, as there may

be instances where it is not feasible to pour concrete around the reinforcement bars [10]. A

preliminary investigation on flexural strength of beam strengthened with NSM technique

conducted at Lule University of Technology in 1996 assessed the initial rectangular FRP rods. In

conjunction with a comprehensive investigation conducted by Lorenzis et al. [4], as well as the

work of Hassan and Rizkalla et al [11] examined circular rods in 2001, the results demonstrated a

significant enhancement in capacity, with improvements ranging from 25.7% to 44.3% compared

to the control beam. However, it is evident that establishing a strong bond is crucial for the

efficacy of this technique. The research undertaken by Nordin and Täljsten [12] revealed that the

sawing of grooves for FRP reinforcement was only feasible when the steel reinforcement has an

adequate level of "depth."](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-2-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 3

Fig. 1. Concrete member strengthened in flexure with NSM FRP.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the efficacy of this technique is contingent upon the

thickness of the concrete cover, a parameter that exhibits variability based on the prevailing

conditions encountered at the construction site. Hence, it may be inferred that outdoor structures,

particularly bridges, may derive greater advantages from the suggested technique in comparison

to inside ones, owing to their higher concrete coverage [9]. According to recent researches

[13,14], examinations have shown that the use of NSM-FRP rods in reinforced concrete beams

might potentially increase the Flexural Strength by up to 60.6%. This enhancement is dependent

on the specific ratios of internal steel reinforcement and the subsequent behavior of the beams.

The researchers investigated the bonding mechanism between NSM-FRP bars and its

implications for flexural strengthening in concrete structures. The study stated earlier made

predictions on the bond length limitations for each side of the beam's center line, with a clear

span of 2500 millimeters. These limitations were estimated to be 150, 550, 800, and 1200

millimeters [15]. The results of the study indicate that the optimal development length for NSM-

CFRP should not be reduced to a value less than 80 times the initial diameter, taking into account

the specific properties of the materials and grooves employed. Conversely, the reinforced beams

exhibited minimal reduction in ultimate load capacity when subjected to the modified epoxy

adhesive. Furthermore, it was observed that the load capacity of the beams exhibited a modest

improvement when the bond lengths exceeded 800 millimeters [16]. According to the results of

the beam bond experiment conducted in reference [17], it was observed that longer rod bonds

were associated with an augmented ultimate load capacity. Consequently, the resistance to

splitting was enhanced through the process of widening the square grooves. In a previous study

[18], the beams, which had a distinct span of 2800 millimeters, were reinforced by employing

adhesive bonds with lengths measuring 2100, 2700, and 3000 millimeters. The utilization of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-3-2048.jpg)

![4 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

epoxy in the NSM system led to the breakdown of the system, resulting in the withdrawal of the

rods and the detachment of the concrete cover from the end of the rods. In spite of the observed

elongation of 3000 millimeters in the bond length, there was no discernible reduction in the

maximum load deflection. Furthermore, the strength of the concrete had minimal influence on

the load-carrying capacity of the reinforced beams [19].A subsequent investigation in this field

examined the application of reinforced beams with less robust bonding, resulting in significant

implications for failure modes such as the detachment of concrete or the extraction of CFRP

rods. Furthermore, the cantilever beams that were reinforced and subjected to testing using a

four-point flexure exhibited identical failure mechanisms, as reported in a previous study [20].

Based on the findings of a separate study [21], the utilization of CFRP strips as near-surface

mounted (NSM) reinforcements, as opposed to EB-CFRP strips, resulted in a significant

enhancement of the load-bearing capacity of reinforced beams, with an increase of 4.8 times.

However, according to a recent study, the utilization of NSM CFRP strips to reinforce GFRP RC

beams may eventually change the failure mode compared to the beams without reinforcement,

resulting in more vulnerable failure modes such CFRP rupture or CFRP debonding [22].

2. Analytical approach

The Figure.2 shows the basic theoretical conditions of internal strain, stress, in the ultimate

section that is under-reinforced with steel ( s sb

ρ < ρ ), and it is strengthened by FRP. The essential

assumptions for this condition are: throughout the cross section, the strain changes linearly, the

section is not cracked at initial, there is a complete bond between the steel and FRP

reinforcements and concrete, 0.003 is the level of concrete strain where the compression failure

occurs, and in the compression area, the Whitney rectangular stress block considered a good

substitution for the nonlinear distribution of stress at ultimate, and Finally, the behavior of steel

is considered elastic-plastic in terms of stress-strain [6].

Fig. 2. Model analysis at ultimate [4].

Since the section is not cracked at first and f s

d > d , the FRP strain f

ε will be almost higher than

the steel strain s

ε . There is a dependency between the nominal flexural uncracked beam strength](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-4-2048.jpg)

![6 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

Likewise, the steel stress is y

f when s sy

A A

. However, in case of s sy

A > A , the steel stress is less

than y

f and have to be calculated by compatibility and equilibrium. By use of this method, in all

samples controlled by concrete failure in this study the ultimate steel stress was equal to yield.

While the steel stress is equal to yield, for the sections controlled by concrete failure, the

compression block (a), FRP reinforcement stress ( f

f ), and nominal moment capacity ( n

M ) can

be obtained from the following equations:

2 '

1

'

( ) 4(0.85) ( )

(2)0.85

f f cu s y c f f sy f f f cu s y

c

A E A f f b A E d A E A f

a

f b

(4a)

1

1

f

f f cu fu

d

f E f

(4b)

( ) ( )

2 2

u f f f s y s

a a

M A f d A f d

(4c)

3. Artificial neural networks methodology

Artificial neural networks are not commonly employed for the purpose of estimating the capacity

of civil engineering structures. However, their inherent capability to effectively identify and

replicate patterns renders them an ideal tool for undertaking such a task [23]. In the context of

FRP strengthening of RC beams, these models assume a highly specialized role since they

possess the capability to address intricate issues that prove challenging to resolve by analytical

methods [24]. This is particularly true in cases when there is a lack of fundamental physical or

mathematical models to guide the resolution of these challenges. Neural-network modelling, a

nonlinear regression model utilized in the life sciences, is grounded on the basic mechanisms of

the human brain [25]. Figure 3 illustrates the representation of typical computational neurons.

The computational neuron possesses analogous characteristics to biological neurons, including

an input, a nerve cell, and an output. The primary step in the modelling of neural networks in the

present study involved the collection of homogeneous experimental data through a

comprehensive analysis of previous studies and identified and selected the variables that have a

significant impact on the outcome. These variables were subsequently designated as input nodes

in the modelling procedure. In a neural network architecture, a node situated on a distinct layer is

responsible for receiving a collection of input values and generating a linear output by utilizing

weights and biases [26]. Neurons exhibit binary activation states, determined by an activation

function. The primary objective of the activation function is to derive non-linear output from a

linearly generated value. The Sigmoid, Tanh, and Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) functions are

widely recognized as the three most prominent activation functions in the field [25]. In the

domain of civil engineering, it has been observed that the Tanh function exhibits superior

performance compared to alternative activation functions when employed as the output layer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-6-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 7

activation function [27]. In order to enhance the predictability of the proposed prediction model,

several neurons were interconnected to create an Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

Fig. 3. Schematic of computational neurons [28].

This neural network consists of one or more hidden layers, an output layer, and a multilayer

perceptron. The architecture of a multilayer perceptron is seen in Figure 5. The architecture of

artificial neural network (ANN) models has a significant impact on their implementation [29].

While there exist alternative training processes, the backpropagation (BP) algorithm is generally

known to produce satisfactory outcomes [30]. The Levenberg-Marquardt method is often

employed as a post-release training algorithm [24]. Prior to the training phase, the acquired data,

consisting of inputs and targets, undergoes normalization or scaling based on known

relationships. This is achieved by reducing the disparity between the values of the variables

under examination across different scales. The equation, denoted as Eq. (1), is employed to

standardize relationships, wherein the values are confined within the range of 0.1 to 0.9, as

observed in the relationships enumerated below:

𝐼𝑆 =

(0.9−0.1)(𝐼−𝐼𝑚𝑖𝑛)

𝐼𝑚𝑎𝑥−𝐼𝑚𝑖𝑛

+ 0.1 (5)

The Levenberg-Marquardt method is utilized to randomly create three sets of input and target

vectors, namely training, validation, and test sets. Various relative percentages are commonly

considered, but, in order to optimize the distribution of the dataset, the training, validation, and

testing subsets are typically allocated 70%, 15%, and 15% respectively [31]. The termination

criterion for network training is determined by the mean square error, specifically by evaluating

the squared difference between the network's outputs and the desired objectives. Lower mean

squared error (MSE) values are associated with improved network performance. Regression

values, which assess the degree of correlation between the outputs of a network and its targets,

have become the prevailing criterion for selecting the appropriate stopping point for a network.

Regression coefficients with a value of 1 indicate a substantial association, whereas regression

coefficients with a value of 0 imply a chance occurrence. By considering these two parameters,

one may effectively determine the optimal network [32]. The formation of the optimal network

occurs through the selection of desirable networks and the careful consideration of the

aforementioned criteria.

∑ Transfer

Output

.

.

.

.

.

.

Bias](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-7-2048.jpg)

![8 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

Fig. 4. A present research program flow chart consists of the proposed model.

As previously mentioned, in this study a feed forward MLP neural network was employed,

consisting of three layers: input, hidden, and output. The input layer represents the characteristic

properties of the behavior of strengthened beams. Given the significant impact of numerous

elements on the Flexural failure mode, it is imperative to meticulously pick input variables or

signatures to achieve an optimal configuration of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN). This is

due to the necessity of selecting the number of input parameters in accordance with the quantity

of training data. In order to accurately describe the system, a multitude of parameters must be

carefully selected. However, it has been established that an increased quantity of input neurons

has a detrimental effect on the efficiency and accuracy of the training process in artificial neural

networks (ANNs).

The activation functions of tan-sigmoid and linear are employed in their respective activation

functions. Training trials were employed to find the optimal number of hidden layer nodes and

determine the most suitable activation functions. The programming language MATLAB was

utilized to develop, train, and deploy an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) employing the back-

propagation technique and the Levenberg-Marquardt training algorithm. The artificial neural

network (ANN) was trained iteratively with the objective of minimizing the performance

function, namely the mean square error (MSE), between the network outputs and the associated

goal values. In a general trend, it was observed that increasing the number of input-target

pairings used during the training process resulted in a higher level of generalization capacity for

the training artificial neural network (ANN) [33].

Start

Investigation of the Flexural

strength of NSM

strengthened Beams

Collection of available

experimental data

Classification and

preparation of Database

Select input parameters

Launching and developing

proposed models based on

artificial neural networks

Verification with test data

Verification

with

experimental

data

Compare results with

existing equations

End

No

Yes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-8-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 9

Fig. 5. ANN Model Architecture.

4. Database and models

In order to configure and train the ANN, 171 experimental tests collected from 39 NSM-FRP-

flexural strengthened concrete beams experimental articles [2,13,38–47,14,48–57,16,58–

65,20,21,34–37]. Table 1 shows the database sample. With regards to the beam geometric ratios,

ratios of reinforcement, the characteristics of the materials and failure loads the chosen dataset

show a high diversity. The database was categorized randomly into three sets: A training set that

contained 70% beams, a validating set using 15% of the beams, and a test set with 15% total

data. The input and output data were scaled between the interval [0.1, 0.9], in order to prohibit

the slow learning rate of at the end points.

5. Prediction of the flexural capacity of NSM-FRP strengthened RC beams

using ANNs

For the data set related to the beam flexural capacity presented here, just 1 output node was

configured in the ANN. However, as previously mentioned among the large range of elements

influencing the behavior of this strengthening approach, the correct selection of the input

parameters is essential for a successful procedure. As a result, we divided the process of

configuring and training the ANN into two steps. After a thorough analysis of the literature in the

first phase, fifteen parameters were selected for the input: (a) beam geometry, which was either

rectangular or T section, (b) NSM-FRP reinforcement f

ratio, (c) cm

f (concrete average

compressive strength) (d) /

a d shear span/depth ratio, (e) distance between FRP bars edge to

support d

L ,(f) elastic modulus of the FRP reinforcement 1

w , (g) design yielding stress of the

steel reinforcement sy

f , (h) FRP length FRP

L , (i) ratio of the steel shear reinforcement sw

, (j)

ratio of the steel longitudinal reinforcement sl

, (k) height of the beam section h , (l) length of

the beam B

L , (m) FRP ultimate strength fu

f (n) width of the beam cross section w

b (o) and

elastic modulus of the steel reinforcement s

E .

Input layer Hidden layer 1 Hidden layer 2 Output layer

Geometry

Input

weight

Output Flexural

Strength

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-9-2048.jpg)

![10 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

Table 1

Flexural Database Sample.

Authors Label

Shape

(T, R)

w

b

(mm)

h

(mm)

B

L

(mm)

FRP

L

(mm)

cm

f

(MPa)

fu

f

(MPa)

sy

f

(MPa)

f

E

(GPa)

s

E

(GPa)

f

sl

sl

Hassan and Rizkalla

2003 [66]

B1 T 150 300 2700 150 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B2 T 150 300 2700 250 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B3 T 150 300 2700 500 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B4 T 150 300 2700 750 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B5 T 150 300 2700 850 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B6 T 150 300 2700 950 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B7 T 150 300 2700 1050 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

B8 T 150 300 2700 1200 48 2000 400 150 200 0.0003 0.0057 0.0042

El-Hacha et al.

2005 [6]

B1 T 150 300 2700 2400 45 1408 400 122.5 200 0.0009 0.008 0.0071

B2 T 150 300 2700 2400 45 1525 400 140 200 0.008 0.008 0.0071

B3 T 150 300 2700 2400 45 2000 400 150 200 0.007 0.008 0.0071

B4 T 150 300 2700 2400 45 1000 400 45 200 0.0025 0.008 0.0071

Barros et al.

2004 [19]

V1R1 R 100 170 1600 1400 46.1 2740 618 158 200 0.0009 0.0038 0.0067

V2R2 R 100 170 1600 1400 46.1 2740 618 158 200 0.0019 0.0057 0.0067

V3R3 R 100 170 1600 1400 46.1 2740 618 158 200 0.0019 0.0071 0.0067

V4r4 R 100 170 1600 1400 46.1 2740 618 158 200 0.0028 0.01 0.0067

Jung et al.

2005 [67]

CRD-NSM R 200 300 3000 2700 31.3 1878 426 121.42 200 0.0012 0.004 0.0077

NSM-PL-25 R 200 300 3000 2700 31.3 2453 426 165.49 200 0.0006 0.004 0.0077

NSM-PL-15 R 200 300 3000 2700 31.3 2453 426 165.49 200 0.0004 0.004 0.0077

ROD-Ml-20 R 200 300 3000 2700 31.3 1878 426 121.42 200 0.0012 0.004 0.0077

PL-Ml-20 R 200 300 3000 2700 31.3 2453 426 165.49 200 0.0006 0.004 0.0077

Nordin and Täljsten

2006 [12]

BS1 R 200 300 4000 3200 64 2800 496 160 210 0.0019 0.0077 0.0077

BS2 R 200 300 4000 4000 62 2800 496 160 210 0.0019 0.0077 0.0077

BM1 R 200 300 4000 3200 64 2800 496 250 210 0.0019 0.0077 0.0077

BM2 R 200 300 4000 4000 65 2800 496 250 210 0.0019 0.0077 0.0077

Teng et al.

2006 [9]

B500 R 150 300 3200 500 35.2 2068 532 131 210 0.008 0.0056 0.0026

B1200 R 150 300 3200 1200 35.2 2068 532 131 210 0.008 0.0056 0.0026

B1800 R 150 300 3200 1800 35.2 2068 532 131 210 0.008 0.0056 0.0026

B2900 R 150 300 3200 2900 35.2 2068 532 131 210 0.008 0.0056 0.0026

Tang et al.

2006 [17]

SPA40-G5-A R 180 250 1500 1500 21 512 398 64 252 0.0106 0.0106 0.0014

SPA20-G5-A R 180 250 1500 1500 37 512 398 64 252 0.0106 0.0106 0.0014

SPA20-G3-A R 180 250 1500 1500 37 650 398 64 252 0.0037 0.0106 0.0014

SNC-G5-A R 180 250 1500 1500 58 512 398 64 252 0.0106 0.0106 0.0014

SNC-G5-B R 180 250 1500 1500 58 512 398 64 252 0.0106 0.0106 0.0014

Al-Mahmoud et al.

2009 [63]

B1 T 150 400 4000 4000 49.5 2068 558 131 210 0.0005 0.0033 0.0031

B2 T 150 400 4000 4000 52.8 2068 558 131 210 0.0005 0.0033 0.0031

C1 T 150 400 4000 4000 52.7 1970 558 147 210 0.0004 0.0033 0.0031

C2 T 150 400 4000 4000 50.1 1970 558 147 210 0.0004 0.0033 0.0031

D1 T 150 400 4000 4000 50.1 690 558 40.8 210 0.0013 0.0033 0.0031

D2 T 150 400 4000 4000 35.2 690 558 40.8 210 0.0013 0.0033 0.0031

Barros and Kotynia

2008 [68]

S1 R 120 170 1000 1000 44.2 2740 788 158.8 200 0.0009 0.0025 0.0025

S2 R 120 170 1000 1000 44.2 2740 627 158.8 200 0.0017 0.0043 0.0025

S3 R 120 170 1000 1000 44.2 2740 627 158.8 200 0.0026 0.0064 0.0025](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-10-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 11

Through randomly choosing the training sample and applying the sensitivity analysis (Milne

index) to every model that satisfied the primary criteria, A preliminary filter was applied to the

input parameters. Using operations between the weight matrices produced in two adjacent layers

of the ANN, the Milne index may determine the relative importance of all input variables in

relation to the output variable [29]. The strategy can be helpful in situations where the index

differs significantly amongst the trained networks. On the other hand, if an input parameter's

index remains low across a large number of networks, it suggests that the parameter is irrelevant

and should be removed.

Fig. 6. Specific details of the proposed ANN Model.

The beam length and the steel reinforcement's Es

elastic modulus was removed in the first

phase. The following condition involved a parametric analysis to assess how well each trained

network can depict the impact of each specific input parameter on the beam capacity. These

investigations were carried out by altering one input parameter while leaving the other

unchanged. The effectiveness of different ANNs in mimicking the physical behavior of the

flexural strengthening of an RC beam was confirmed by parameter analysis. Additionally, for

every set of input parameter, there were between 8 and 20 hidden nodes, and training was carried

out for every possible configuration. /

a d shear span/depth ratio and ratio of the steel shear

reinforcement sw

were found to be less effective in ANN at the second phase. The final 10

variables were used as input variables. For each network, the mean square error between its

output after training and the associated target values in the training and validation sets is initially

estimated. The MSE value was smaller, hence the evaluated network received a higher point. The

ANNs whose predictions agreed with the results of the experimental testing would produce

Start

Data Collection

Select the Input Parameters

Beam

Geometry

NSM-

FRP

ratio

concrete

strength

shear

span/dep

th ratio

FRP

elastic

modulus

FRP

length

shear

ratio

(steel)

longitudi

nal ratio

(steel)

FRP

ultimate

strength

Target = Flexural Strength of Reinforced Beam

ANN

Data Normalization

Divide the Data into Sets

Creating a feed forward-back

propagation neural network

Update number of nodes

Train the network

Obtain the new Model

Calculate Correction Factors

Select reference values

Is network criteria

satisfied

Check the criteria

Verify against experimental

Data

Compare with the existing

models

End

Yes

No](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-11-2048.jpg)

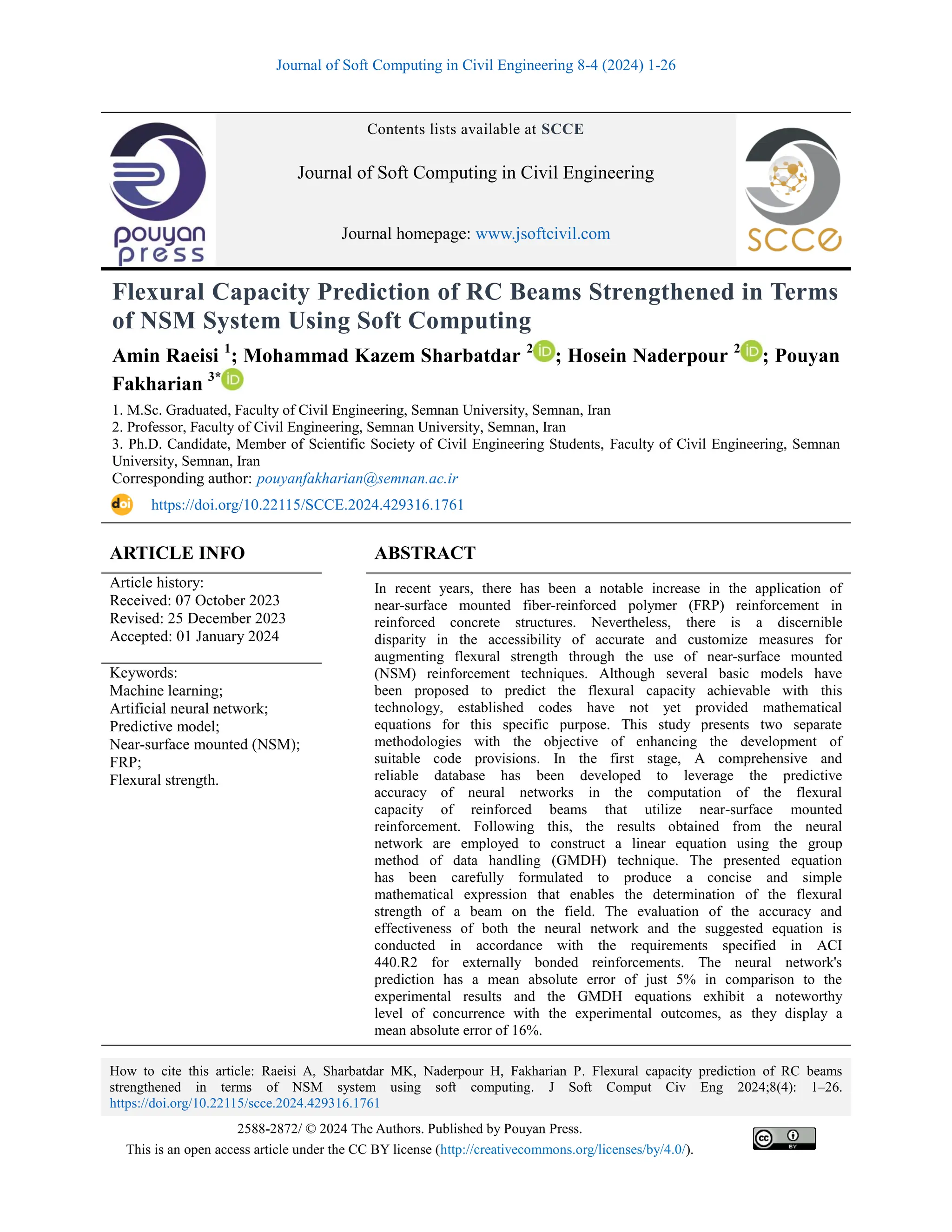

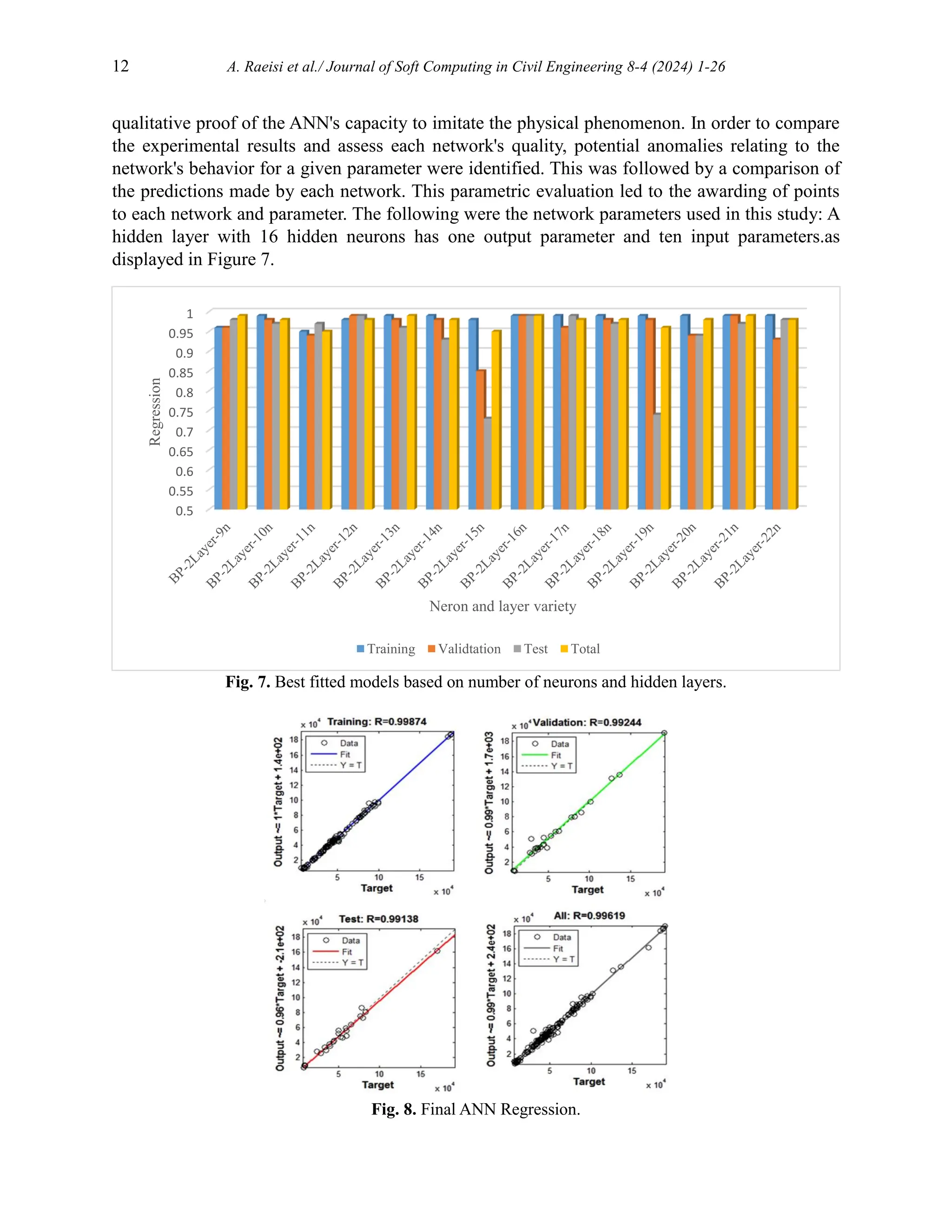

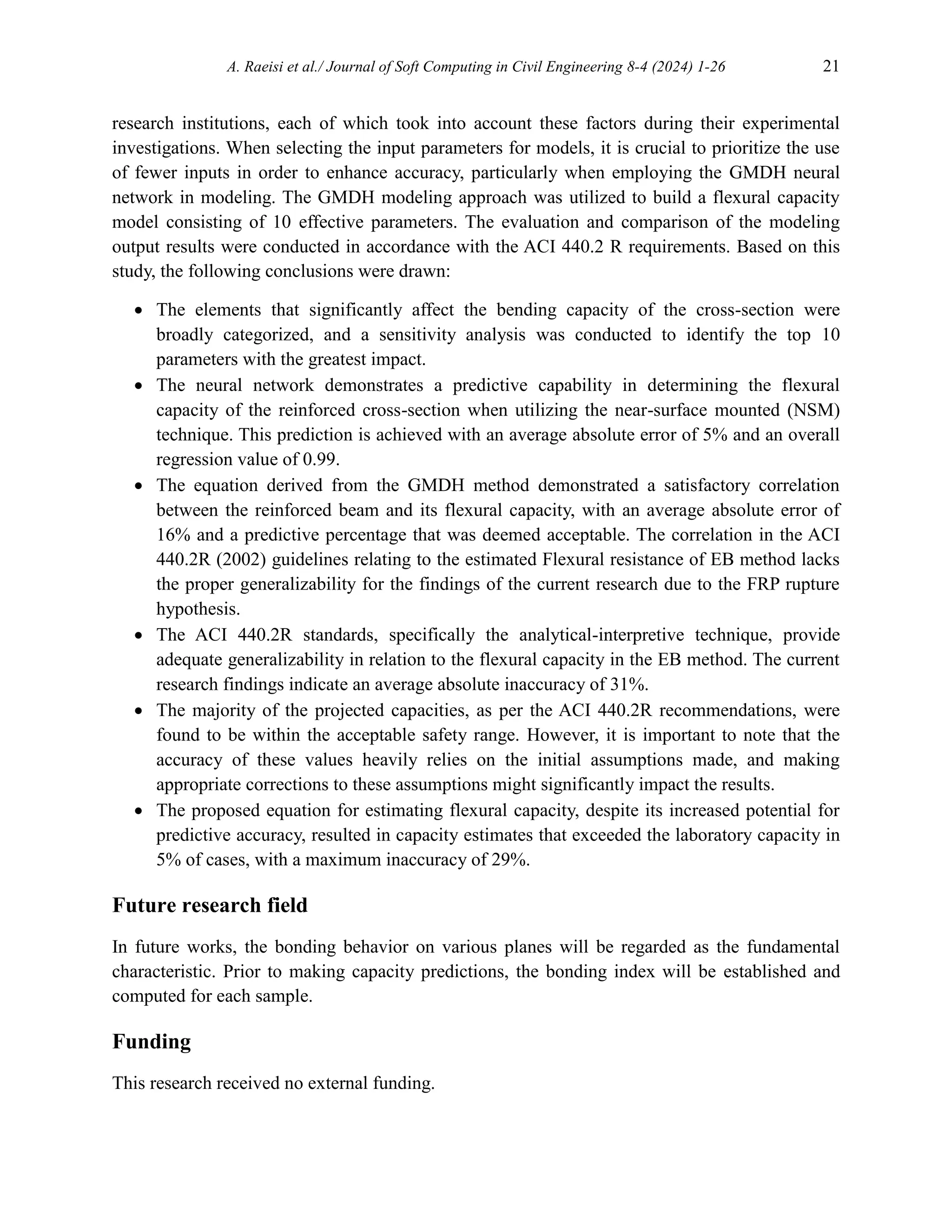

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 13

Fig. 9. Flexural ANN with 1 hidden layer and 16 hidden neurons.

The proposed ANN model could predict the flexural strength of NSM strengthened beams with

mean absolute error of just 5% in comparison to the experimental results. Figures 10 through 12

illustrate how ANNs outperform conventional models in terms of capacity prediction. However,

from the standpoint of engineering design, it may be argued that using straightforward design

equations is a more useful method for determining the strength of NSM-FRP Flexure

strengthened beams. The current study's proposal of design equations to determine the flexure

capacity of RC beams NSM-FRP strengthened in flexure is one of its objectives. In accordance

with the observed behavior of the analyses performed using neural networks, we suggest an

optimization strategy to generate simple and accurate flexure design equations for NSM-FRP

flexure reinforced RC beams. The optimization strategy is created in GMDH [24] due to the fact

that GMDH algorithms are specifically suitable for handling multi objective issues.

Fig. 10. ANN Predicted Flexural Strength comparison with Experimental.

0

20000

40000

60000

80000

100000

120000

140000

160000

180000

200000

0 20000 40000 60000 80000 100000 120000 140000 160000 180000 200000

Experimental

Flexural

Strength

(kN.mm)

Predicted Flexural Strength (kN.mm)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-13-2048.jpg)

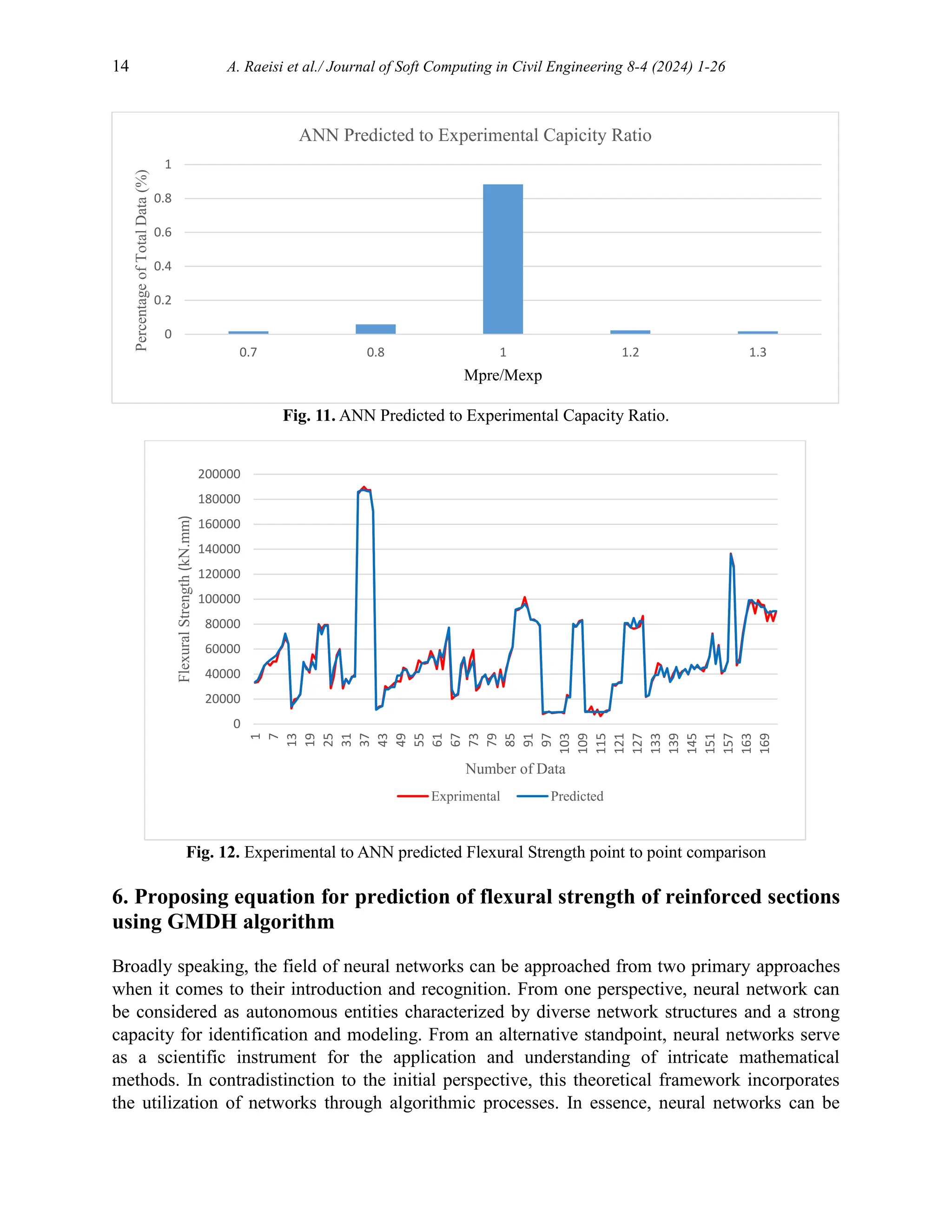

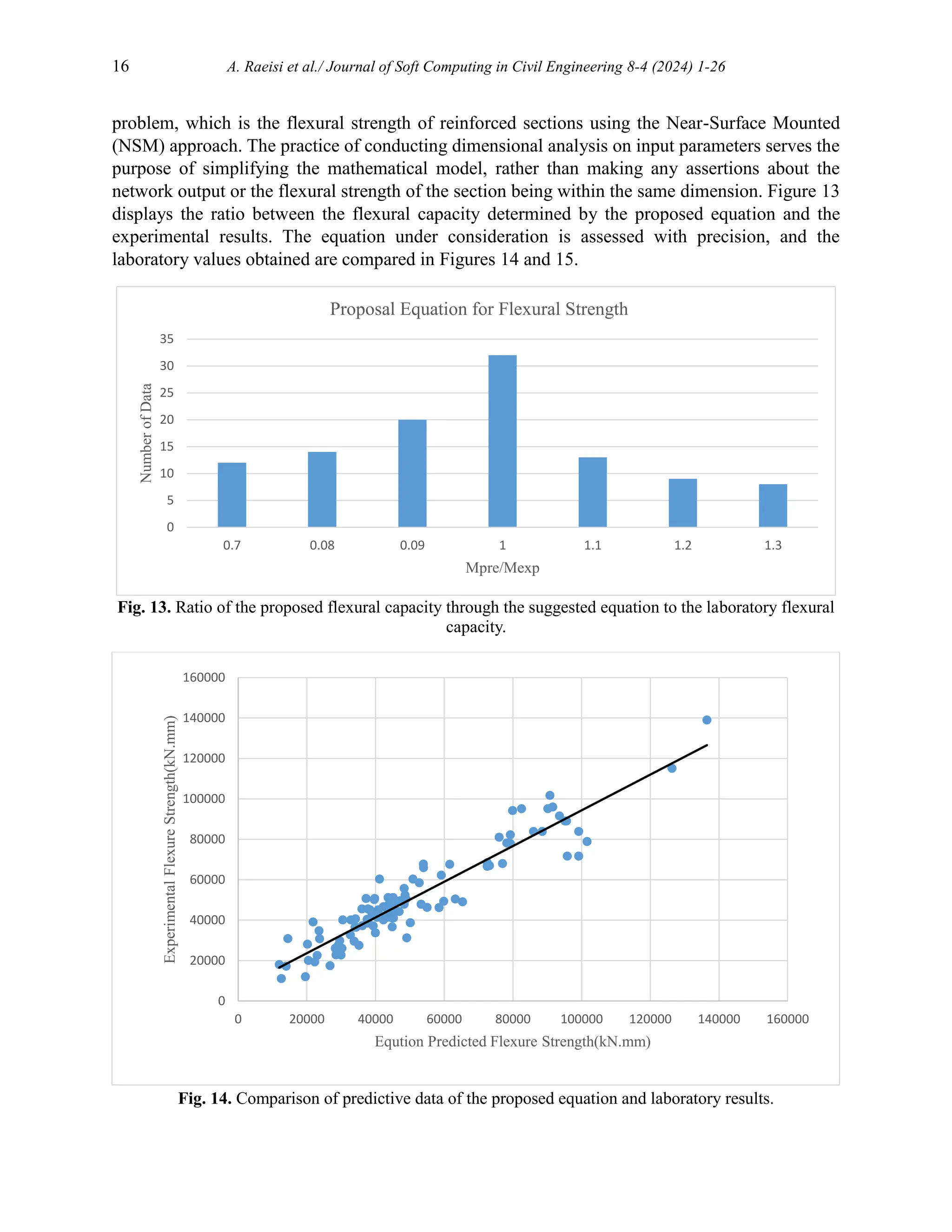

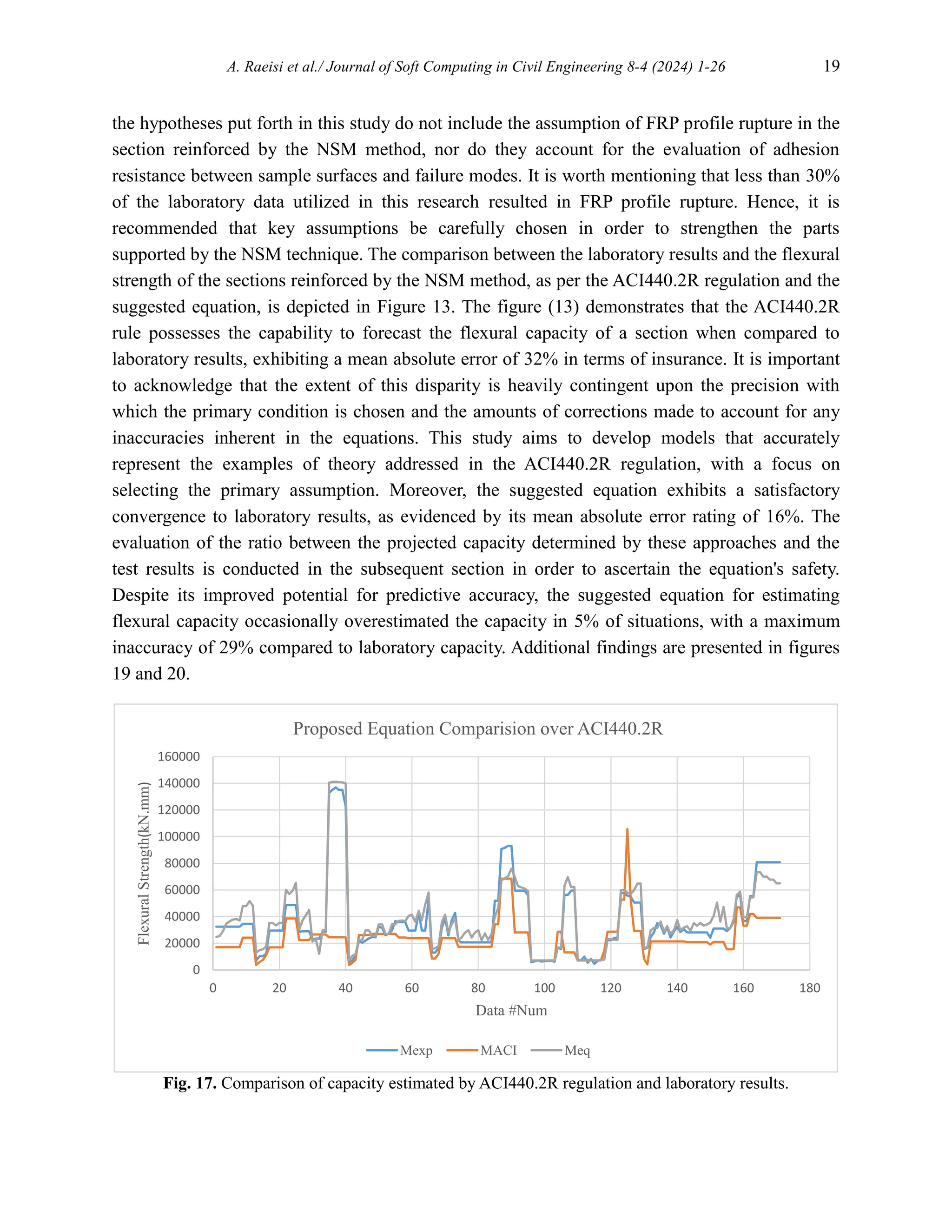

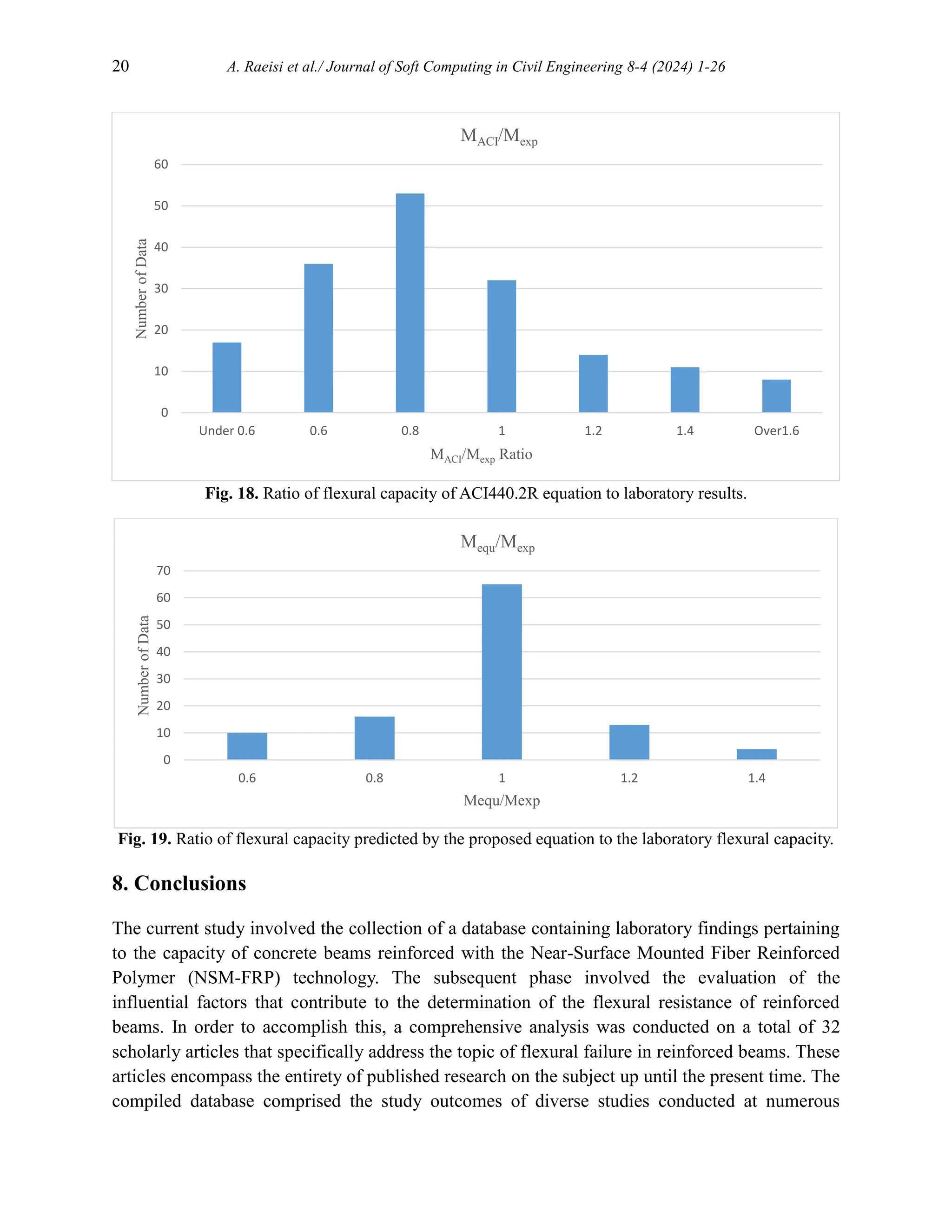

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 17

Fig. 15. Point-by-point comparison of laboratory and proposed flexural strengths by equation in training

mode.

7. Comparison of the proposed equation with ACI 440.2R and FIB guideline

As indicated in the introductory section, there is currently no rule that provides a particular

equation for the flexural capacity of reinforced beams using the Near Surface Mounted (NSM)

approach. Hence, a comparison is made between the equation presented by ACI 440.2R [1],

which is utilized for the estimate of flexural capacity of reinforced beams by the external bonded

(EB) method, and the recommended equation. The equation for determining the flexural capacity

of a reinforced section using the Equivalent Bending (EB) method as specified in the ACI440.2R

regulation is derived by accounting for the contribution of each section of the element and

incorporating the safety factor 𝜸𝒇 in the calculation of the flexural strength of the section's Fiber

Reinforced Polymer (FRP) component. Based on empirical observations, it is postulated that the

fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) profile in the specified segment attains its ultimate strength. In

the context of the regulation pertaining to external bonded reinforcement, it has been observed

that the equation proposed for determining the share of FRP flexural capacity in relation to the

total capacity does not incorporate the safety factor 𝜸𝒇. The equation governing the regulation

and its associated variables are delineated as follows:

𝑀𝑅𝑑 = 𝐴𝑠𝑙 × 𝑓𝑠𝑦𝑑(𝑑𝑠 − 0.4𝑥) + 𝛾𝑓𝐴𝑓𝑓

𝑓𝑒(ℎ − 0.4𝑥) (7a)

𝑓𝑓𝑒 = 𝐸𝑓 ∗ Ɛ𝑓𝑢 (7b)

𝛾𝑓 = 0.85 (7c)

The comparison between the flexural capacity of the section, as determined by the ACI440.2R

regulation, and the flexural capacity estimated by the proposed model, is presented in Figure 17

alongside the test data. Based on the visual representation provided, it can be inferred that the

occurrence of FRP rupture resulted in a notable disparity between the flexural capacity as

estimated by regulatory guidelines and the outcomes obtained from laboratory experimentation.

This assumption highlights a significant discrepancy in the ability to accurately predict the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-17-2048.jpg)

![18 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

flexural capacity of a section reinforced by the Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) method compared

to the Externally Bonded (EB) technique. This discrepancy arises from the larger cross-sectional

area of Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) profiles used in the NSM method, as opposed to the

FRP sheets employed in the EB technique. It is important to note that this assessment is

subjective and requires verification to establish its validity.

Fig. 16. Comparison of the capacity estimated by the equation of ACI440.2R regulation and laboratory

results.

In the updated edition of the ACI440.2R regulation [69], the aforementioned equation has been

substituted with the utilization of a traditional analytical equation that is based on fundamental

assumptions. The accuracy of this equation is evaluated in accordance with the calculations

performed. In these estimations, the initial assumption considers only two primary modes of

failure for the sample, namely the crushing of compressive concrete and the rupture of the FRP

profile. The accuracy and error of the dimensions of the neural axis site are taken into

consideration. Furthermore, the estimation of strain in fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) concrete

and profile is conducted under the assumption that the strain exhibits linearity across the section.

The dominance of FRP profile rupture assumption is contingent upon the strain obtained being

greater than the maximum strain exhibited by the FRP material. Furthermore, the maximum

tensile strength of the Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) profile is considered to be the utmost

measure of energy and strain. Subsequently, the strain and energy of metal rebar are computed by

employing the principle of strain adaptation within the section. The determination of the neutral

axis location is achieved by employing mathematical formulae, which are afterwards utilized to

evaluate its position. This computed value is then compared to the initial assumption made, and

any necessary adjustments are made accordingly. The method presents challenges in both the

initial determination and subsequent verification of the primary estimate for the neutral axis,

which can impact the overall accuracy of the final selection. Furthermore, it should be noted that

0

50000

100000

150000

200000

250000

300000

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

Flexural

Strength(kN.mm)

Data #Num

Proposed Equation Comparision over ACI440.2Rcode

Mexp MACI Meq](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-18-2048.jpg)

![22 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors contribution statement

A.R, H.N, M.K: Conceptualization; A.R, P.F: Data curation; A.R, H.N, M.K: Formal analysis;

A.R, P.F: Investigation; A.R, H.N, M.K: Methodology; H.N, M.K: Project administration; FA:

Resources; A.R: Software; H.N, M.K: Supervision; H.N, M.K: Validation; A.R: Visualization;

A.R, H.N, M.K: Roles/Writing – original draft; A.R, H.N, M.K, P.F: Writing – review & editing.

References

[1] 440.2R-17: Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for

Strengthening Concrete Structures. 2017. https://doi.org/10.14359/51700867.

[2] Effiong JU, Ede AN. Experimental Investigation on the Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete

Beams Using Externally Bonded and Near-Surface Mounted Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer

Composites—A Review. Materials (Basel) 2022;15:5848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175848.

[3] Bilotta A, Ceroni F, Di Ludovico M, Nigro E, Pecce M, Manfredi G. Bond Efficiency of EBR and

NSM FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Members. J Compos Constr 2011;15:757–72.

https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000204.

[4] Lorenzis L De, Nanni A, Tegola A La. Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete Structures with Near

Surface Mounted FRP Rods. Int. Meet. Compos. Mater., 2000, p. 1–8.

[5] De Lorenzis L, Nanni A. Bond between near-surface mounted fiber-reinforced polymer rods and

concrete in structural strengthening. ACI Struct J 2002;99:123–32. https://doi.org/10.14359/11534.

[6] El-Hacha R, Rizkalla SH, Kotynia R. Modelling of Reinforced Concrete Flexural Members

Strengthened with Near-Surface Mounted FRP Reinforcement. SP-230 7th Int. Symp. Fiber-

Reinforced Polym. Reinf. Concr. Struct., vol. SP-230, American Concrete Institute; 2005, p. 1681–

700. https://doi.org/10.14359/14916.

[7] Taleb Obaidat Y, Barham WS, Aljarah AH. New anchorage technique for NSM-CFRP flexural

strengthened RC beam using steel clamped end plate. Constr Build Mater 2020;263:120246.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120246.

[8] Jalali M, Sharbatdar MK, Chen J-F, Jandaghi Alaee F. Shear strengthening of RC beams using

innovative manually made NSM FRP bars. Constr Build Mater 2012;36:990–1000.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.06.068.

[9] Teng JG, De Lorenzis L, Wang B, Li R, Wong TN, Lam L. Debonding Failures of RC Beams

Strengthened with Near Surface Mounted CFRP Strips. J Compos Constr 2006;10:92–105.

https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2006)10:2(92).

[10] Sharaky IA, Torres L, Comas J, Barris C. Flexural response of reinforced concrete (RC) beams

strengthened with near surface mounted (NSM) fibre reinforced polymer (FRP) bars. Compos

Struct 2014;109:8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.10.051.

[11] Hassan TK, Rizkalla SH. Bond Mechanism of Near-Surface-Mounted Fiber-Reinforced Polymer

Bars for Flexural Strengthening of Concrete Structures. ACI Struct J 2004;101:830–9.

https://doi.org/10.14359/13458.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-22-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 23

[12] Nordin H, Täljsten B. Concrete Beams Strengthened with Prestressed Near Surface Mounted

CFRP. J Compos Constr 2006;10:60–8. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2006)10:1(60).

[13] Kara IF, Ashour AF, Köroğlu MA. Flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams

strengthened with prestressed near-surface-mounted FRP reinforcements. Compos Part B Eng

2016;91:371–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.01.023.

[14] Seo S, Choi K, Kwon Y, Lee K. Flexural Strength of RC Beam Strengthened by Partially De-

bonded Near Surface-Mounted FRP Strip. Int J Concr Struct Mater 2016;10:149–61.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40069-016-0133-z.

[15] Wu G, Dong Z, Wu Z, Zhang L. Performance and Parametric Analysis of Flexural Strengthening

for RC Beams with NSM-CFRP Bars. J Compos Constr 2014;18:1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000451.

[16] Costa IG, Barros JAO. Flexural and shear strengthening of RC beams with composite materials –

The influence of cutting steel stirrups to install CFRP strips. Cem Concr Compos 2010;32:544–53.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2010.03.003.

[17] Tang WC, Balendran RV, Nadeem A, Leung HY. Flexural strengthening of reinforced lightweight

polystyrene aggregate concrete beams with near-surface mounted GFRP bars. Build Environ

2006;41:1381–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.05.029.

[18] Boukhezar M, Samai ML, Mesbah HA, Houari H. Flexural behaviour of reinforced low-strength

concrete beams strengthened with CFRP plates. Struct Eng Mech 2013;47:819–38.

https://doi.org/10.12989/sem.2013.47.6.819.

[19] Barros J, Sena-cruz J, Dias S, Ferreira D, Fortes A. Near surface mounted CFRP-based technique

for the strengthening of concrete structures. Concrete 2004:1–13.

[20] Ceroni F. Experimental performances of RC beams strengthened with FRP materials. Constr Build

Mater 2010;24:1547–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.03.008.

[21] Soliman SM, El-Salakawy E, Benmokrane B. Flexural behaviour of concrete beams strengthened

with near surface mounted fibre reinforced polymer bars. Can J Civ Eng 2010;37:1371–82.

https://doi.org/10.1139/L10-077.

[22] Barris C, Sala P, Gómez J, Torres L. Flexural behaviour of FRP reinforced concrete beams

strengthened with NSM CFRP strips. Compos Struct 2020;241:112059.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112059.

[23] Lee S, Lee C. Prediction of shear strength of FRP-reinforced concrete flexural members without

stirrups using artificial neural networks. Eng Struct 2014;61:99–112.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.01.001.

[24] Naderpour H, Poursaeidi O, Ahmadi M. Shear resistance prediction of concrete beams reinforced

by FRP bars using artificial neural networks. Measurement 2018;126:299–308.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.05.051.

[25] Cortez P, Embrechts MJ. Using sensitivity analysis and visualization techniques to open black box

data mining models. Inf Sci (Ny) 2013;225:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2012.10.039.

[26] Ghanizadeh AR, Ghanizadeh A, Asteris PG, Fakharian P, Armaghani DJ. Developing bearing

capacity model for geogrid-reinforced stone columns improved soft clay utilizing MARS-EBS

hybrid method. Transp Geotech 2023;38:100906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2022.100906.

[27] Chen L, Fakharian P, Rezazadeh Eidgahee D, Haji M, Mohammad Alizadeh Arab A, Nouri Y.

Axial compressive strength predictive models for recycled aggregate concrete filled circular steel

tube columns using ANN, GEP, and MLR. J Build Eng 2023;77:107439.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107439.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-23-2048.jpg)

![24 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

[28] Chen Q, Norcio AF, Wang J. Neural Network Based Stereotyping for User Profiles. Neural

Comput Appl 2000;9:259–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005210070003.

[29] Naderpour H, Haji M, Mirrashid M. Shear capacity estimation of FRP-reinforced concrete beams

using computational intelligence. Structures 2020;28:321–8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2020.08.076.

[30] Naderpour H, Kheyroddin A, Amiri GG. Prediction of FRP-confined compressive strength of

concrete using artificial neural networks. Compos Struct 2010;92:2817–29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2010.04.008.

[31] Naderpour H, Alavi SA. A proposed model to estimate shear contribution of FRP in strengthened

RC beams in terms of Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System. Compos Struct 2017;170:215–27.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.03.028.

[32] Naderpour H, Rafiean AH, Fakharian P. Compressive strength prediction of environmentally

friendly concrete using artificial neural networks. J Build Eng 2018;16:213–9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.01.007.

[33] Fakharian P, Rezazadeh Eidgahee D, Akbari M, Jahangir H, Ali Taeb A. Compressive strength

prediction of hollow concrete masonry blocks using artificial intelligence algorithms. Structures

2023;47:1790–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.12.007.

[34] Mehany S, Mohamed HM, Benmokrane B. Flexural Behavior and Serviceability Performance of

Lightweight Self-Consolidating Concrete Beams Reinforced with Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer

Bars. ACI Struct J 2023;120:47–60. https://doi.org/10.14359/51738502.

[35] Uzdil O, Sayın B, Coşgun T. Examination of parameters impacting flexural and shear

strengthening of RC beams. J Struct Eng Appl Mech 2022;5:117–34.

https://doi.org/10.31462/jseam.2022.03117134.

[36] Askar MK, Hassan AF, Al-Kamaki YSS. Flexural and shear strengthening of reinforced concrete

beams using FRP composites: A state of the art. Case Stud Constr Mater 2022;17:e01189.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01189.

[37] Al-Obaidi S, Saeed YM, Rad FN. Flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete beams with NSM-

CFRP bars using mechanical interlocking. J Build Eng 2020;31:101422.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101422.

[38] Panahi M, Zareei SA, Izadi A. Flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete beams through

externally bonded FRP sheets and near surface mounted FRP bars. Case Stud Constr Mater

2021;15:e00601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00601.

[39] Suliman AKS, Jia Y, Mohammed AAA. Experimental evaluation of factors affecting the behaviour

of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by NSM CFRP strips. Structures 2021;32:632–40.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.03.058.

[40] Al-Abdwais AH, Al-Mahaidi RS. Experimental and finite element analysis of flexural performance

of RC beams retrofitted using near-surface mounted with CFRP composites and cement adhesive.

Eng Struct 2021;241:112429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112429.

[41] Jahani Y, Baena M, Gómez J, Barris C, Torres L. Experimental Study of the Effect of High Service

Temperature on the Flexural Performance of Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) Carbon Fiber-

Reinforced Polymer (CFRP)-Strengthened Concrete Beams. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13:920.

https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13060920.

[42] Murad Y, Abu-AlHaj T. Flexural strengthening and repairing of heat damaged RC beams using

continuous near-surface mounted CFRP ropes. Structures 2021;33:451–62.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.04.079.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-24-2048.jpg)

![A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26 25

[43] Abdallah M, Al Mahmoud F, Khelil A, Mercier J, Almassri B. Assessment of the flexural behavior

of continuous RC beams strengthened with NSM-FRP bars, experimental and analytical study.

Compos Struct 2020;242:112127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112127.

[44] Imjai T, Setkit M, Garcia R, Figueiredo FP. Strengthening of damaged low strength concrete beams

using PTMS or NSM techniques. Case Stud Constr Mater 2020;13:e00403.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2020.e00403.

[45] Yazdani N, Aljaafreh T, Beneberu E. Concrete beam flexural strengthening with anchored pre-

saturated CFRP laminates. Compos Struct 2020;235:111733.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111733.

[46] Abdelkarim OI, Ahmed EA, Mohamed HM, Benmokrane B. Flexural strength and serviceability

evaluation of concrete beams reinforced with deformed GFRP bars. Eng Struct 2019;186:282–96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.02.024.

[47] Obaidat YT, Ashteyat AM, Obaidat AT. Performance of RC Beam Strengthened with NSM-CFRP

Strip Under Pure Torsion: Experimental and Numerical Study. Int J Civ Eng 2020;18:585–93.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-019-00487-2.

[48] Panahi M, Izadinia M. A Parametric Study on the Flexural Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete

Beams with Near Surface Mounted FRP Bars. Civ Eng J 2018;4:1917. https://doi.org/10.28991/cej-

03091126.

[49] Sharaky IA, Baena M, Barris C, Sallam HEM, Torres L. Effect of axial stiffness of NSM FRP

reinforcement and concrete cover confinement on flexural behaviour of strengthened RC beams:

Experimental and numerical study. Eng Struct 2018;173:987–1001.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.07.062.

[50] Yaseen SA. Flexural Behavior of Self Compacting Concrete T-Beams Reinforced with AFRP.

Eurasian J Sci Eng 2018;4. https://doi.org/10.23918/eajse.v4i2p178.

[51] Daghash SM, Ozbulut OE. Flexural performance evaluation of NSM basalt FRP-strengthened

concrete beams using digital image correlation system. Compos Struct 2017;176:748–56.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.06.021.

[52] Haddad RH, Almomani OA. Recovering flexural performance of thermally damaged concrete

beams using NSM CFRP strips. Constr Build Mater 2017;154:632–43.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.211.

[53] Al-Saadi NTK, Mohammed A, Al-Mahaidi R. Performance of RC beams rehabilitated with NSM

CFRP strips using innovative high-strength self-compacting cementitious adhesive (IHSSC-CA)

made with graphene oxide. Compos Struct 2017;160:392–407.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.10.084.

[54] Goldston MW, Remennikov A, Sheikh MN. Flexural behaviour of GFRP reinforced high strength

and ultra high strength concrete beams. Constr Build Mater 2017;131:606–17.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.094.

[55] Khalifa AM. Flexural performance of RC beams strengthened with near surface mounted CFRP

strips. Alexandria Eng J 2016;55:1497–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2016.01.033.

[56] Mahal M, Täljsten B, Blanksvärd T. Experimental performance of RC beams strengthened with

FRP materials under monotonic and fatigue loads. Constr Build Mater 2016;122:126–39.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.06.060.

[57] Yang JM, Min KH, Shin HO, Yoon YS. Behavior of High-Strength Concrete Beams Reinforced

with Different Types of Flexural Reinforcement and Fiber. Adv. FRP Compos. Civ. Eng., vol. L,

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011, p. 275–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-

17487-2_58.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-25-2048.jpg)

![26 A. Raeisi et al./ Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering 8-4 (2024) 1-26

[58] Nurbaiah MN, Hanizah AH, Nursafarina A, Nur Ashikin M. Flexural behaviour of RC beams

strengthened With externally bonded (EB) FRP sheets or Near Surface Mounted (NSM) FRP rods

method. 2010 Int. Conf. Sci. Soc. Res. (CSSR 2010), IEEE; 2010, p. 1232–7.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CSSR.2010.5773725.

[59] Al-mahmoud F, Castel A, François R, Tourneur C. RC beams strengthened with NSM CFRP rods

and modeling of peeling-off failure 2010;92:1920–30.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2010.01.002.

[60] Akbarzadeh H, Maghsoudi AA. Experimental and analytical investigation of reinforced high

strength concrete continuous beams strengthened with fiber reinforced polymer. Mater Des

2010;31:1130–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2009.09.041.

[61] Perera R, Vique J, Arteaga A, Diego A De. Shear capacity of reinforced concrete members

strengthened in shear with FRP by using strut-and-tie models and genetic algorithms. Compos Part

B Eng 2009;40:714–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2009.06.008.

[62] Wang B, Teng JG, Lorenzis L De, Zhou L, Ou J, Jin W, et al. Strain monitoring of RC members

strengthened with smart NSM FRP bars. Constr Build Mater 2009;23:1698–711.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.07.027.

[63] Al-Mahmoud F, Castel A, François R, Tourneur C. Strengthening of RC members with near-

surface mounted CFRP rods. Compos Struct 2009;91:138–47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.040.

[64] Hashemi SH, Rahgozar R, Maghsoudi AA. Flexural testing of high strength reinforced concrete

beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. Int J Eng Trans B Appl 2009;22:131–46.

[65] Barros JAO, Dias SJE, Lima JLT. Efficacy of CFRP-based techniques for the flexural and shear

strengthening of concrete beams. Cem Concr Compos 2007;29:203–17.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.09.001.

[66] Hassan T, Rizkalla S. Investigation of Bond in Concrete Structures Strengthened with Near Surface

Mounted Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer Strips. J Compos Constr 2003;7:248–57.

https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2003)7:3(248).

[67] Jung WT, Park YH, Park JS, Kang JY, You YJ. Experimental investigation on flexural behavior of

RC beams strengthened by NSM CFRP reinforcements. Am. Concr. Institute, ACI Spec. Publ., vol.

SP-230, 2005, p. 795–805.

[68] Barros J, Kotynia R. Possibilities and challenges of NSM for the flexural strengthening of RC

structures. Proc. 4th Int. Conf. FRP Compos. Civ. Eng. CICE 2008, 2008, p. 22–4.

[69] Soudki K, Alkhrdaji T. Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems

for Strengthening Concrete Structures (ACI 440.2R-02). Struct. Congr. 2005, Reston, VA:

American Society of Civil Engineers; 2005, p. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1061/40753(171)159.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sccevolume8issue4pages1-26-250603072131-8b2b23e2/75/Flexural-Capacity-Prediction-of-RC-Beams-Strengthened-in-Terms-of-NSM-System-Using-Soft-Computing-26-2048.jpg)