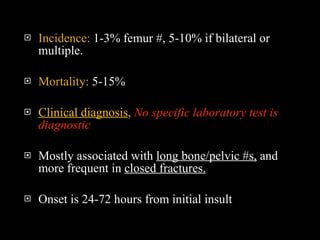

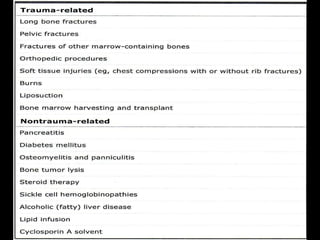

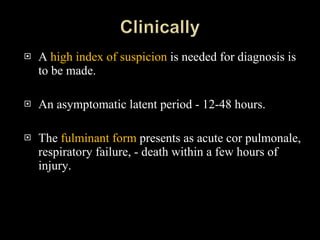

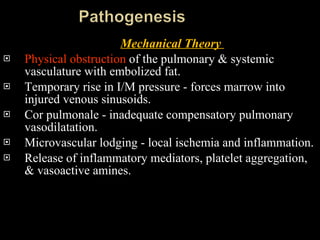

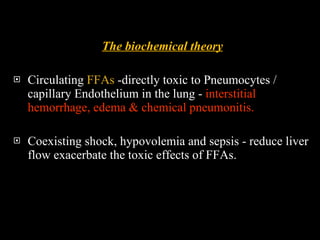

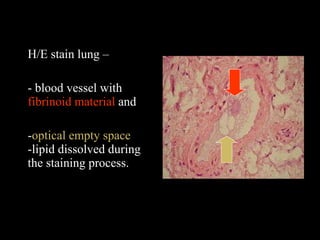

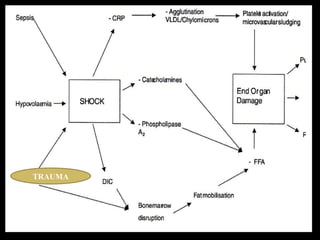

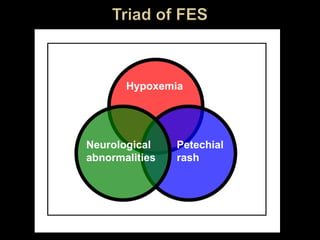

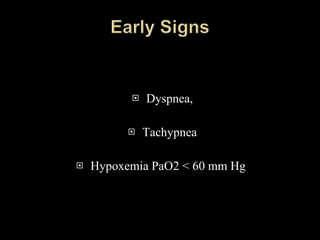

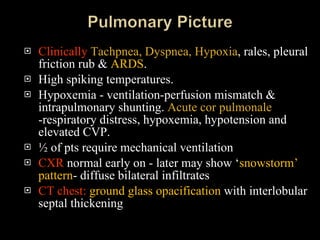

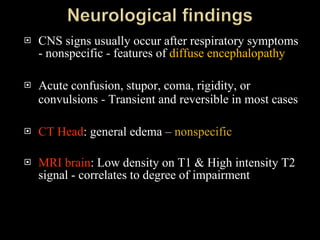

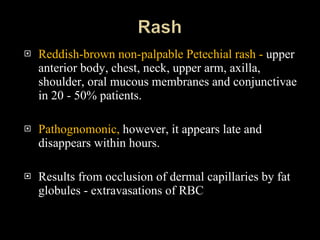

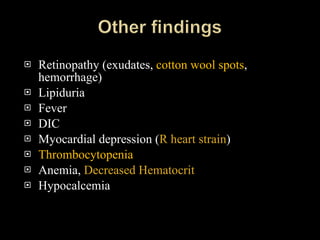

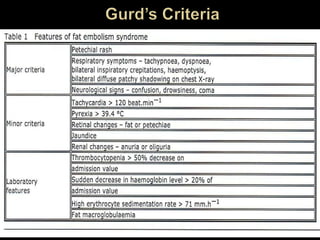

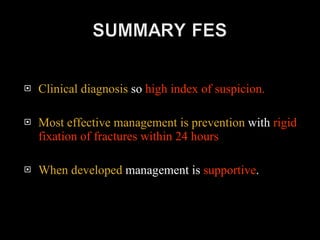

Fat embolism syndrome is a complication that can occur after long bone fractures, with onset of symptoms between 12-72 hours. It involves the blockage of small blood vessels in the lungs and other organs by fat globules, and can lead to respiratory distress, hypoxemia, neurological symptoms and petechial rash. Diagnosis is clinical and supported by criteria involving respiratory, neurological and skin findings. Treatment focuses on prevention through early surgical fixation of fractures, as well as supportive care of respiratory, cardiac and neurological complications. Outcomes vary from complete resolution to long-term deficits.