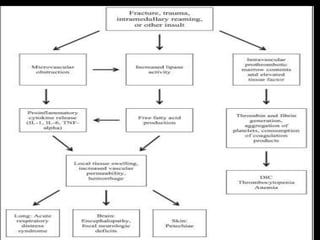

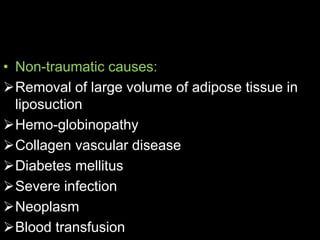

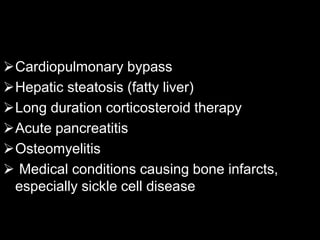

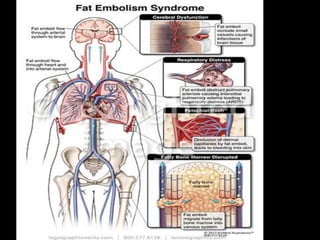

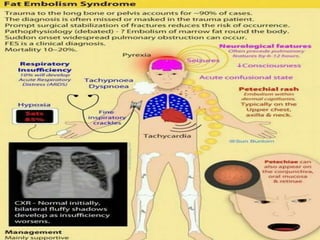

1. Fat embolism syndrome is a serious manifestation of fat embolism that can cause multi-system dysfunction, most commonly affecting the lungs and brain.

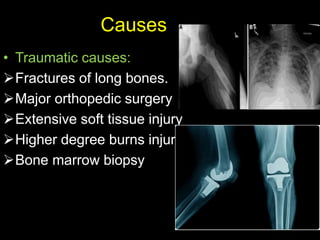

2. It occurs most often after long bone fractures, especially femur fractures, when fat droplets enter the bloodstream and lodge in the pulmonary capillaries or brain vasculature.

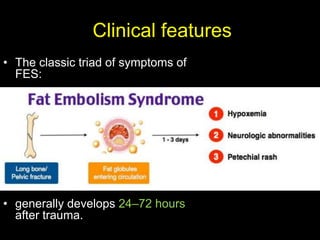

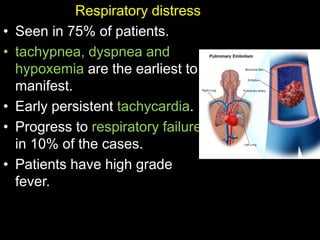

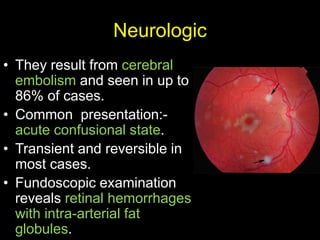

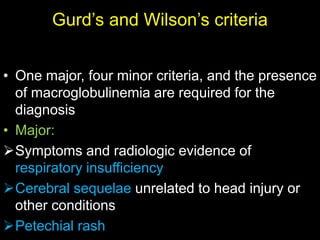

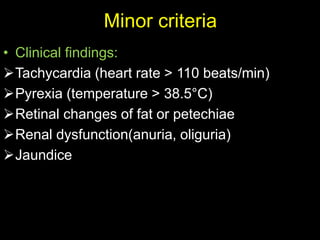

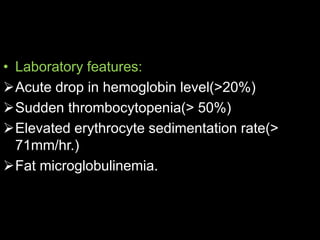

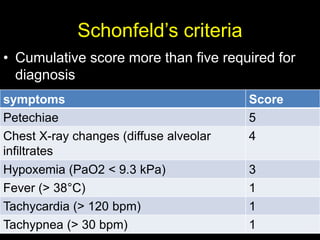

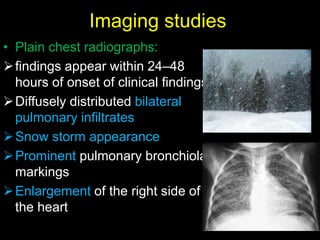

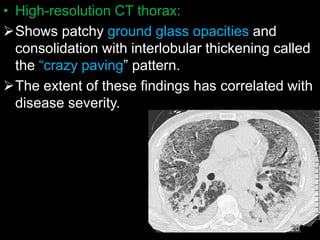

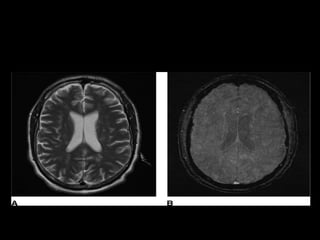

3. Clinical features include a triad of respiratory distress, neurological changes like confusion, and petechial rash. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria and imaging may show changes in the lungs and brain. Treatment is supportive with oxygen, ventilation if needed, IV fluids and steroids. Prognosis is generally good if respiratory failure can be prevented.