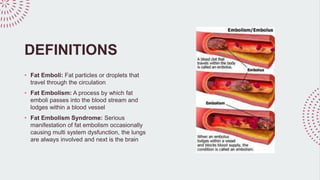

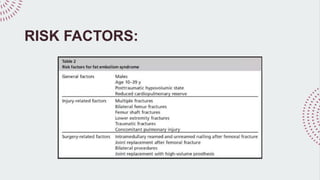

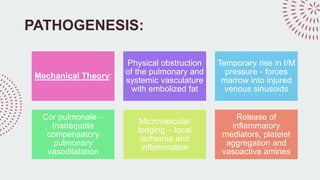

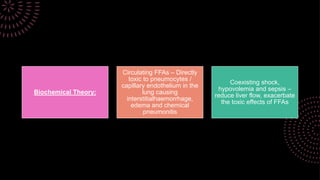

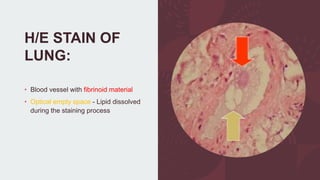

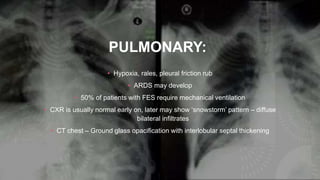

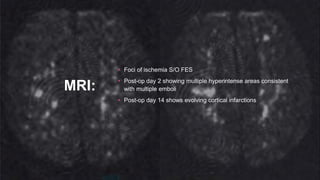

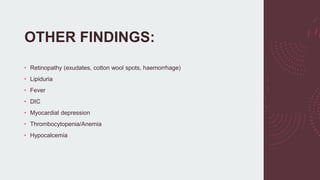

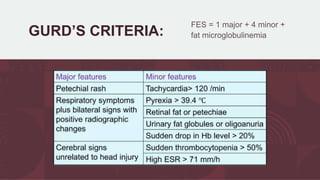

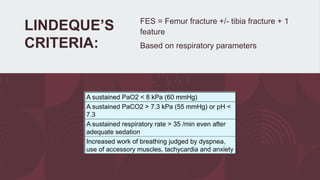

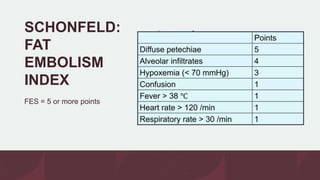

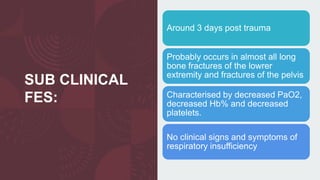

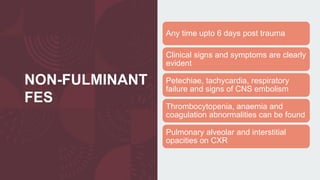

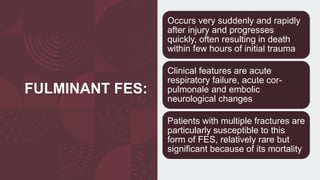

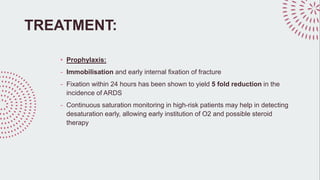

Fat embolism syndrome is a clinical diagnosis characterized by a triad of hypoxemia, neurological abnormalities, and petechial rash that develops within 24-72 hours of long bone fractures or other trauma. Fat particles released from the bone marrow can cause pulmonary and systemic complications by lodging in the lungs and other organs. While supportive care focuses on oxygenation, ventilation, and hemodynamic stability, the most effective prevention method is early surgical fixation of fractures within 24 hours to reduce risk. Outcomes range from full recovery to respiratory failure and death, depending on severity.