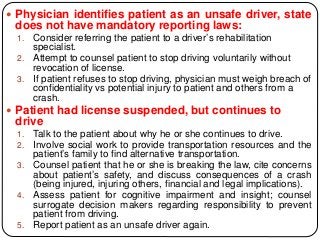

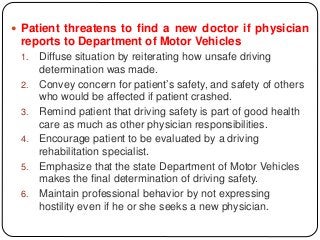

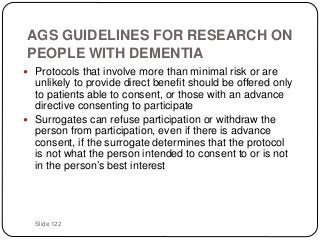

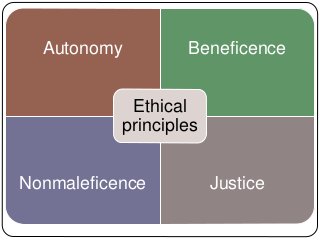

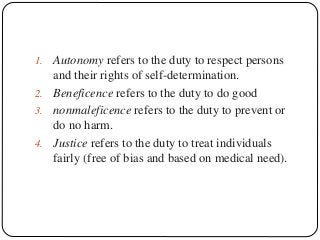

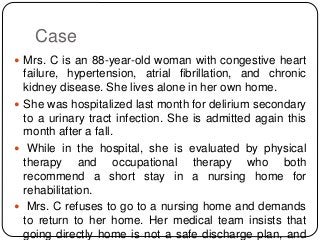

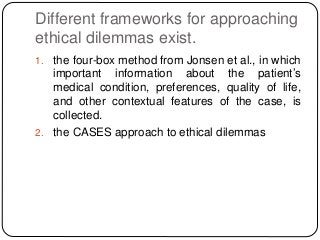

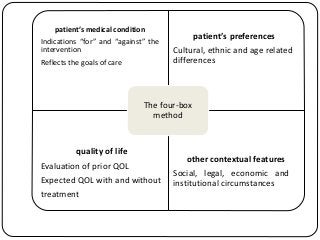

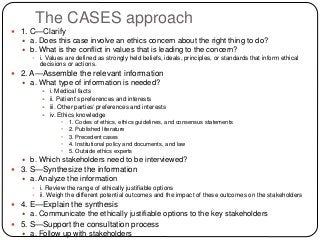

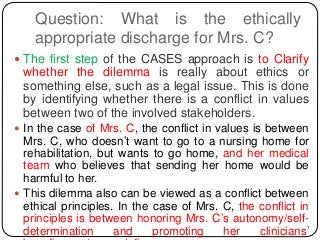

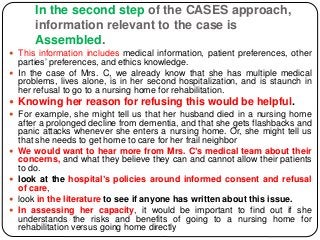

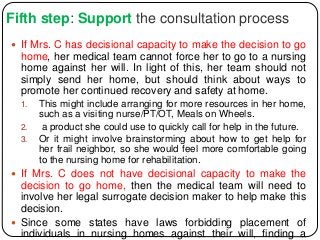

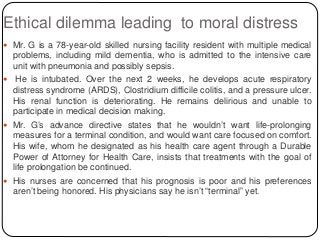

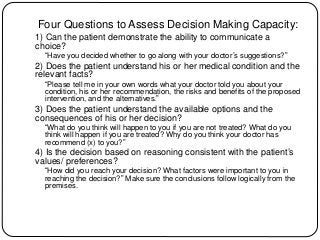

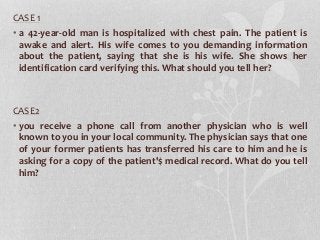

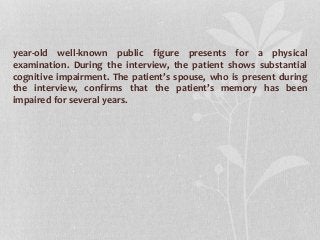

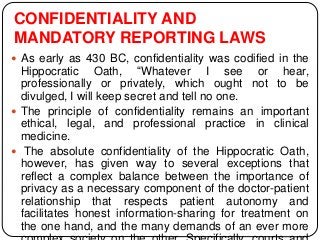

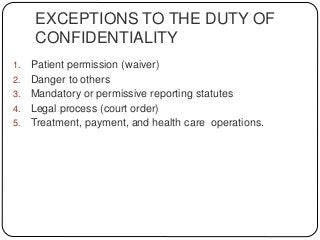

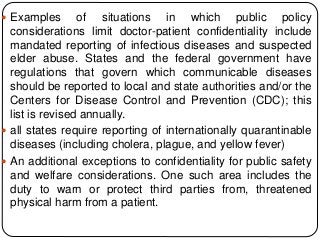

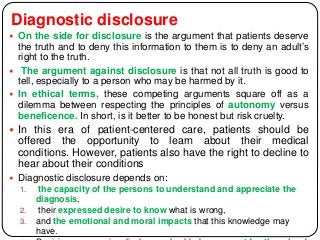

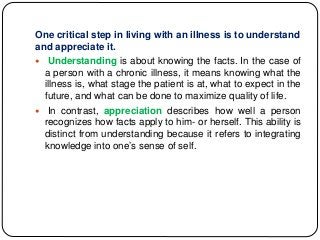

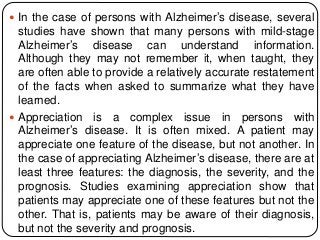

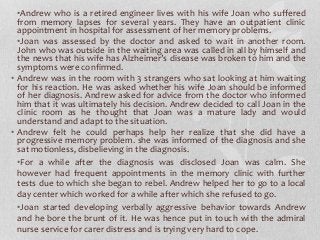

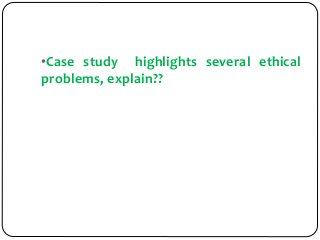

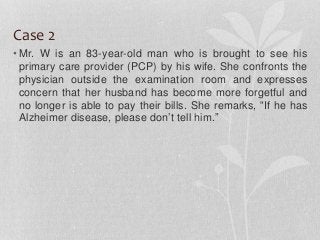

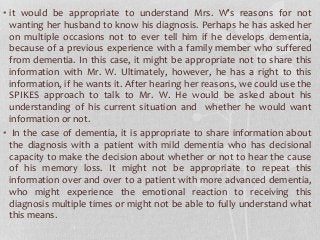

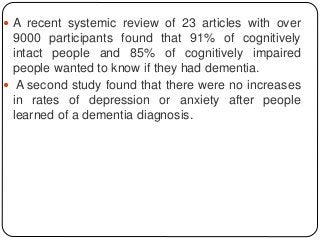

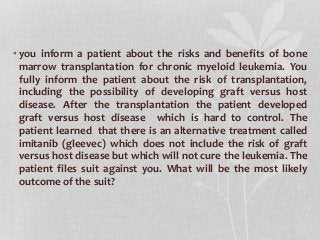

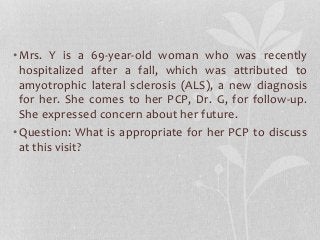

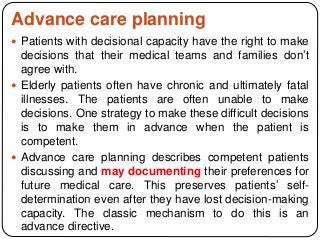

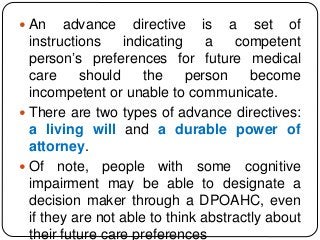

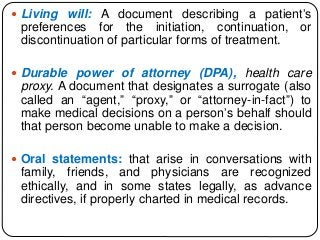

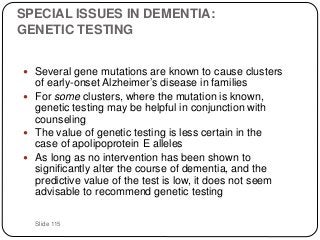

The document summarizes key ethical issues in geriatric care including principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence. It discusses approaches to analyzing ethical dilemmas, including the four-box method and CASES framework. It also covers topics like moral distress, assessing decision-making capacity, and confidentiality/mandatory reporting laws. Specifically, it provides a case example of an elderly patient refusing discharge to a nursing home and walks through applying the CASES approach to determine the ethically appropriate discharge plan.

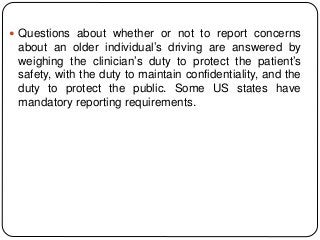

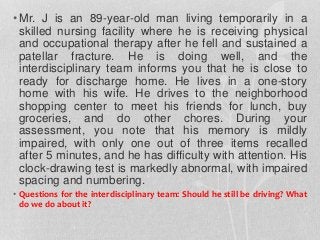

![STRATEGIES TO EMPLOY WHEN WORKING WITH OLDER

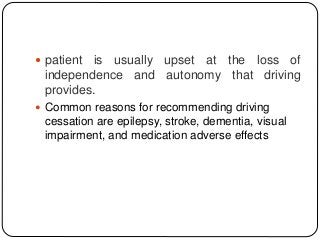

ADULTS REGARDING DRIVING CESSATION

Patient threatens to sue physician if reported to

Department of Motor Vehicles:

1. Clearly document how the patient was determined to

be an unsafe driver (driving fitness evaluation,

assessing driving-related skills [ADReS] battery,

driving rehabilitation referral, medications, etc).

2. Advise patient that the state has the ultimate

responsibility to determine licensing.

3. If physician is mandated to report in that state,

physician must report. The physician should also

advise the patient of this.

4. Consult malpractice insurance or legal counsel to

determine degree of risk (physicians generally run](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicalissues-181103224337/85/Ethical-issues-in-geriatric-care-119-320.jpg?cb=1676624462)