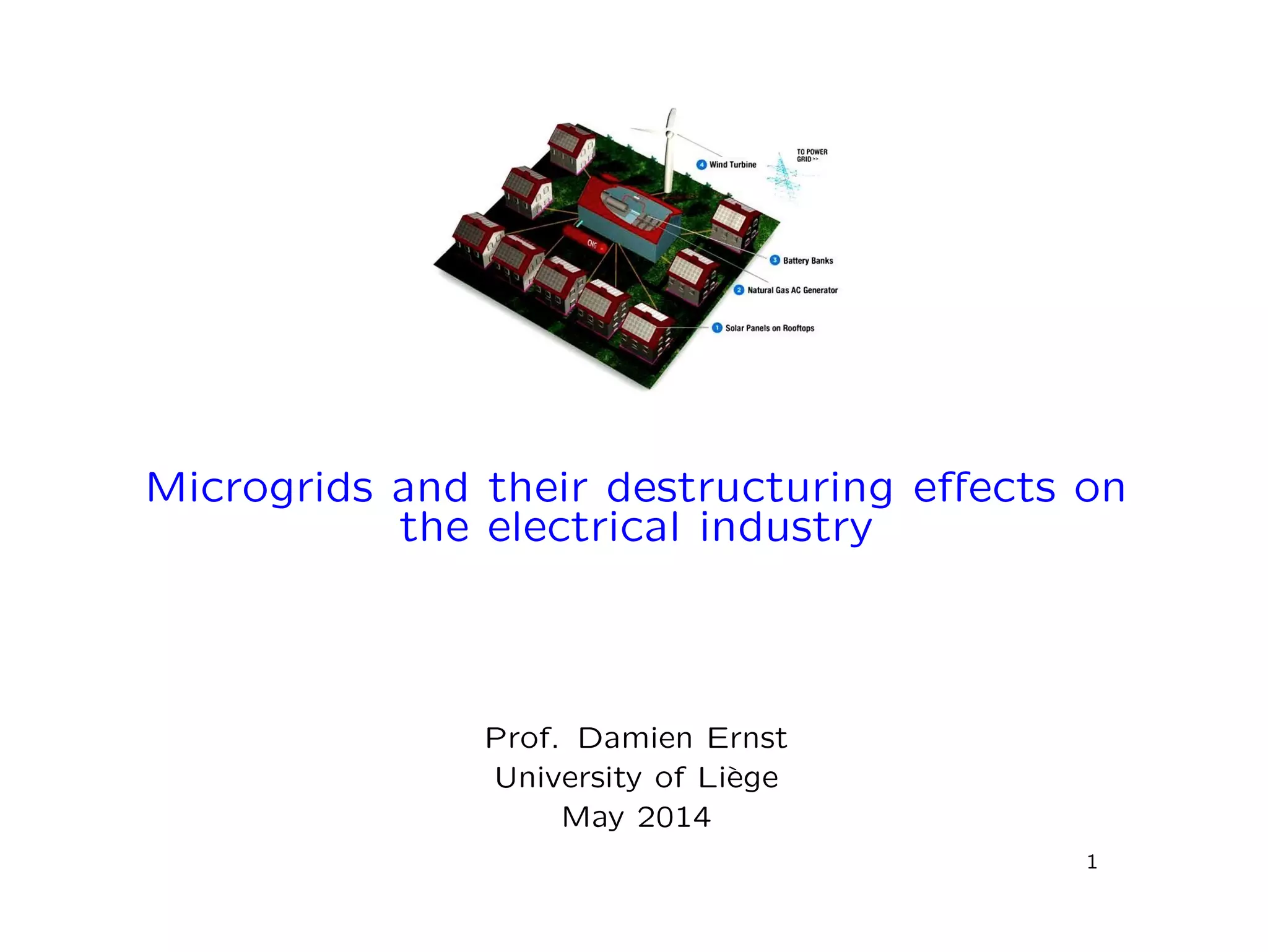

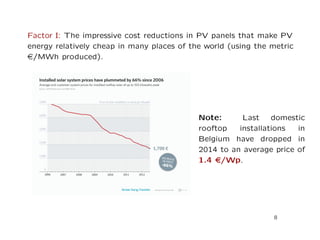

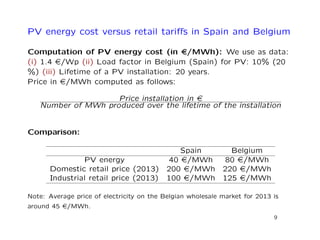

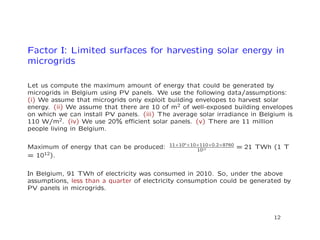

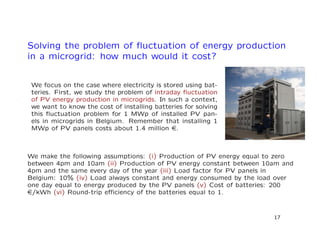

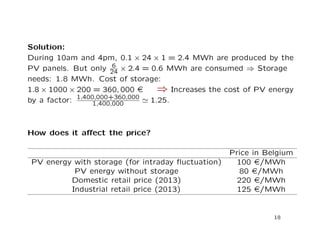

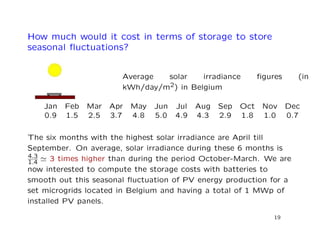

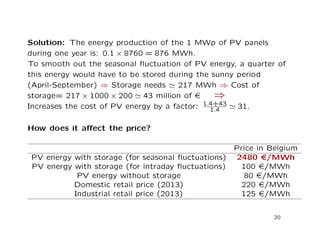

This document discusses microgrids and their potential effects on the traditional electrical grid system. It begins by defining microgrids as electrical systems that include loads and distributed energy sources that can operate connected to or independent of the broader utility grid. It then discusses six key factors driving the development of microgrids, including declining costs of solar PV panels. While microgrids may disrupt the traditional grid model, the document argues they will likely be limited by available surface area for solar and changes to energy market regulations. It advises major grid players to develop solutions like large-scale hydrogen storage and influence regulations to maintain a role for centralized grids alongside distributed generation from microgrids.