The document discusses several key concepts related to teaching English Language Learners (ELLs), including:

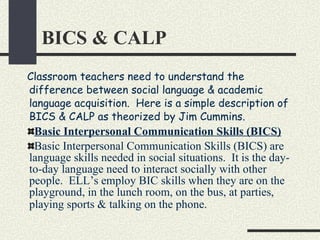

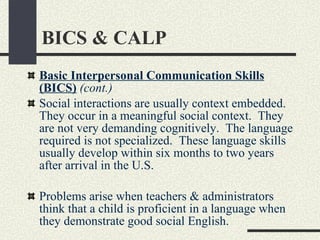

1. It describes the difference between Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP), noting that BICS develops quicker but CALP takes longer and is needed for academic success.

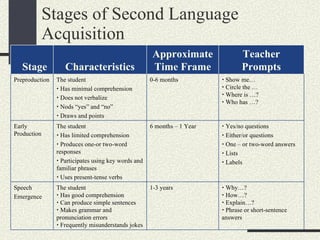

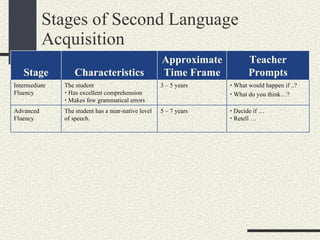

2. It outlines the typical stages of second language acquisition, from pre-production to advanced fluency, and examples of teacher prompts at each stage.

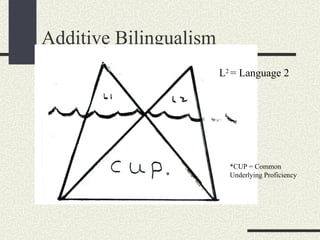

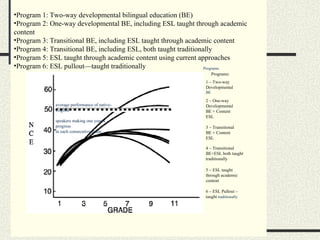

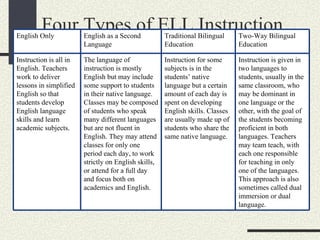

3. It discusses the benefits of various ELL instructional programs and notes that two-way bilingual education leads to the highest average performance for ELL students.