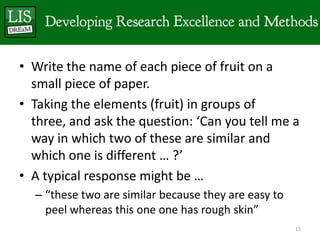

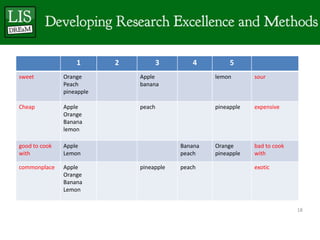

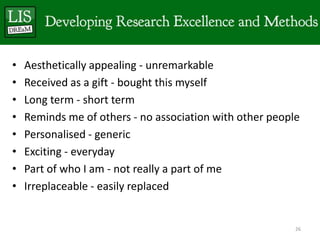

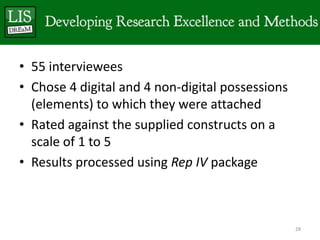

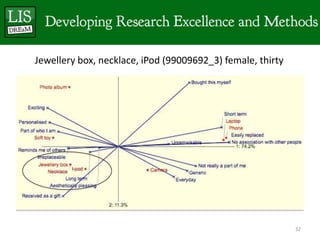

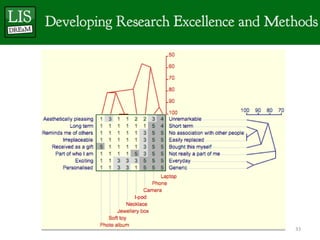

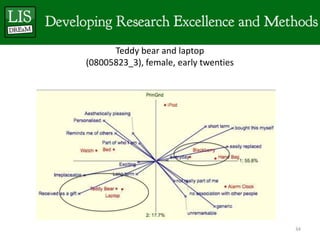

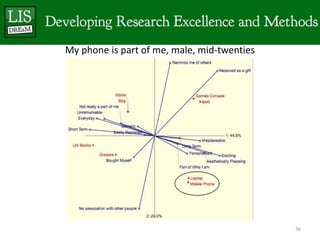

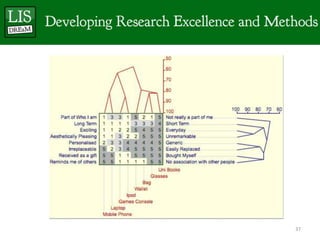

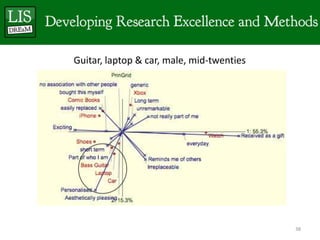

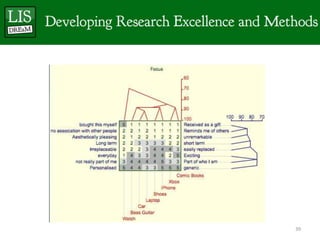

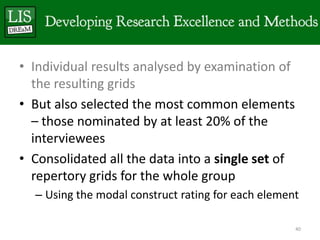

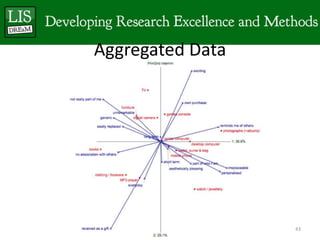

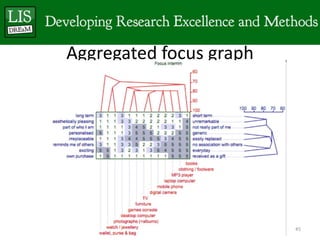

The document discusses personal construct theory, emphasizing how individuals create and test hypotheses about their experiences to form their unique personality constructs. It details the repertory grid technique for eliciting these constructs, exploring people's emotional attachments to both digital and non-digital artefacts, revealing significant commonality in how they perceive these items. Findings indicate that emotional attachment exists for digital artefacts, challenging assumptions about their disposability and suggesting they can hold personal significance similar to traditional physical objects.