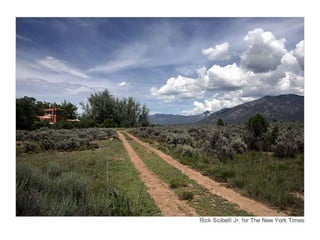

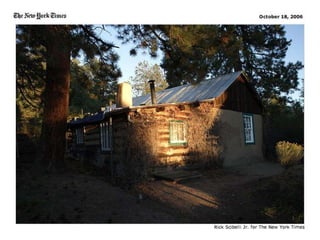

D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930) was an English writer best known for his novels Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, and Women in Love. He had a difficult childhood and worked as a teacher before dedicating himself fully to writing. His novels explored themes of sexuality and challenged Victorian notions of morality. Lawrence believed that industrialization had damaged society and sought to reconnect people with nature. He spent time in Italy, Australia, New Mexico, drawing inspiration from rural landscapes and mythology.

![Nietzsche’s influence on Lawrence religious morality can only ever be a morbid abstraction that denies the way in which we live our lives now to imagine that a detached, peaceable & pure life is better than the dynamic struggles and pleasures of bodily experience is immoral ‘ I know the greatness of Christianity: it is a past greatness. […] But now I live in 1924 and the Christian venture is done. The adventure is gone out of Christianity. We must start on a new venture towards God.’ ‘ Books’ (1924), published in Phoenix (1936)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stmawr-110415062557-phpapp01/85/D-H-Lawrence-St-Mawr-lecture-slides-10-320.jpg)

![‘‘ Everywhere we see the vulgarity of desolation spreading. […] to me the mere thought that a tree is convertible into cash is disgusting. It is through us, and to our shame […] that the woods no longer give shelter to Pan. Pan is dead. That is why the woods do not shelter him.’ And he began to tell the striking story of the mariners who were sailing near the coast at the time of the birth of Christ, and three times heard a loud voice saying: ‘The great God Pan is dead.’’ E.M. Forster, ‘The Story of a Panic’, 1902, Collected Short Stories](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stmawr-110415062557-phpapp01/85/D-H-Lawrence-St-Mawr-lecture-slides-13-320.jpg)

![‘ And yet here, in America, the oldest of all, old Pan is still alive. […] In the days before man got too much separated off from the universe, he was Pan, along with all the rest. As a tree still is. […] And the tree is still within the allness of Pan. […] Of course, if I like to cut myself off, and say it is all bunk, a tree is merely so much lumber not yet sawn, then in a great measure I shall be cut off. […] One can shut many, many doors of receptivity in oneself; or one can open many doors that are shut.’ ‘ Pan in America’, Phoenix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stmawr-110415062557-phpapp01/85/D-H-Lawrence-St-Mawr-lecture-slides-14-320.jpg)

![‘ This was the death of the great Pan. The idea and the engine came between man and all things, like a death. The old connexion, the old Allness, was severed, and can never be ideally restored. Great Pan is dead. […] A conquered universe, a dead Pan, leaves us nothing to live with. You have to abandon the conquest, before Pan will live again.’ ‘ Pan in America’, Phoenix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stmawr-110415062557-phpapp01/85/D-H-Lawrence-St-Mawr-lecture-slides-21-320.jpg)

![‘ I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had. It certainly changed me forever. Curious as it may sound, it was New Mexico that liberated me from the present era of civilization, the great era of material and mechanical development. […] And years, even in the exquisite beauty of Sicily, right among the old Greek paganism that still lives there, had not shattered the essential Christianity on which my character was established. […] In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly, and the old world gave way to a new.’ ‘ New Mexico’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stmawr-110415062557-phpapp01/85/D-H-Lawrence-St-Mawr-lecture-slides-23-320.jpg)