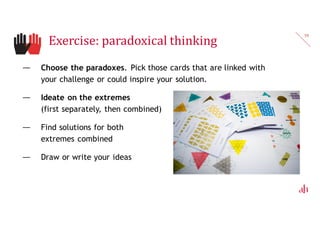

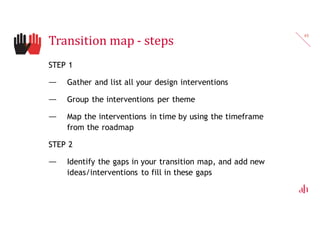

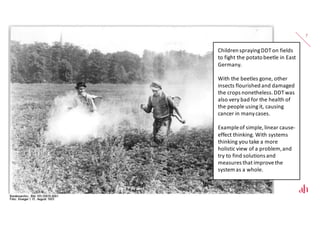

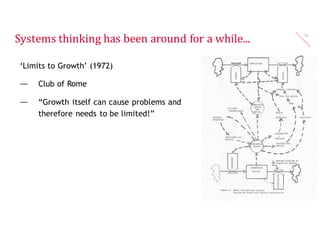

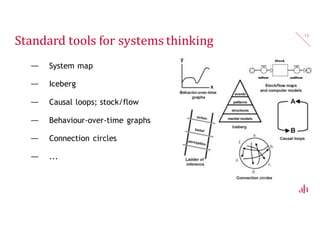

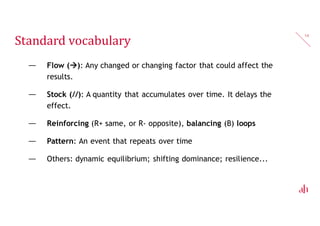

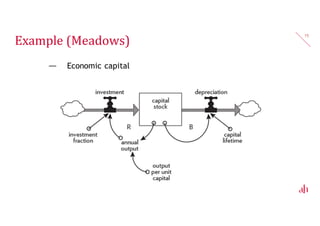

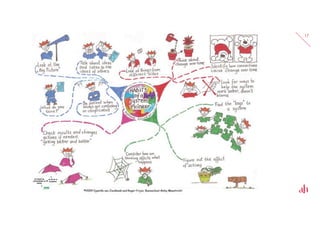

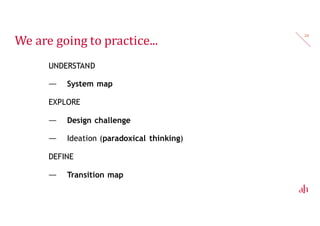

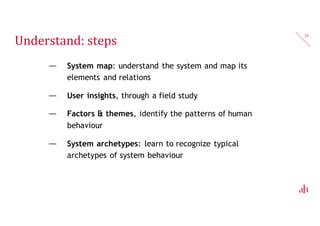

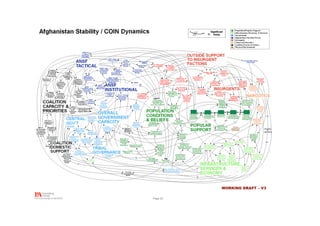

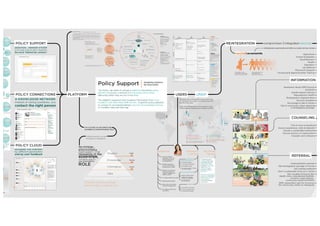

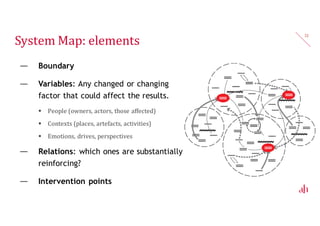

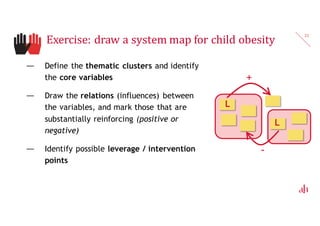

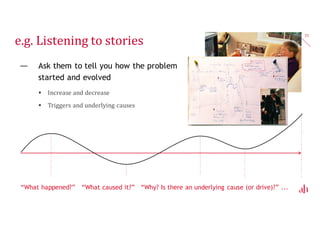

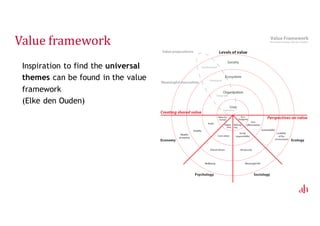

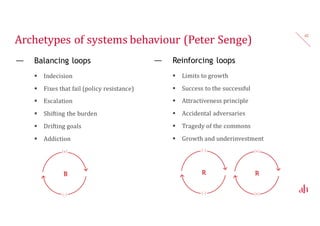

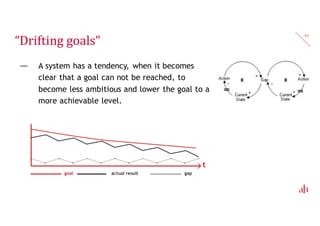

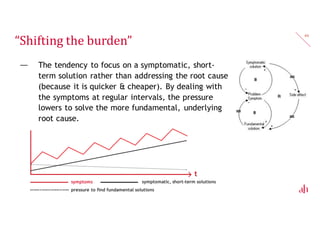

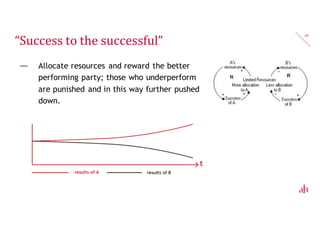

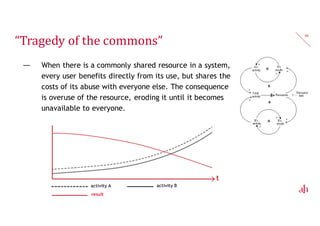

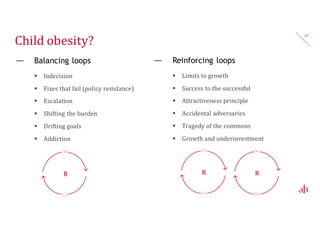

The document outlines the principles of systems thinking and its application in the design process, highlighting the importance of viewing problems holistically rather than through a linear cause-effect lens. It discusses tools such as system maps, causal loops, and archetypes to analyze complex issues like childhood obesity, encouraging collaborative and comprehensive approaches to problem-solving. The goal is to create effective design interventions that address interconnected challenges by understanding and mapping the intricate relations within systems.

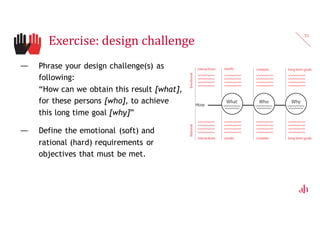

![Exercise: design challenge

52

— Phrase your design challenge(s) as

following:

“How can we obtain this result [what],

for these persons [who], to achieve

this long time goal [why]”

— Define the emotional (soft) and

rational (hard) requirements or

objectives that must be met.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asisyspresentation-final-150925140201-lva1-app6891/85/Design-Tools-for-Systems-Thinking-52-320.jpg)