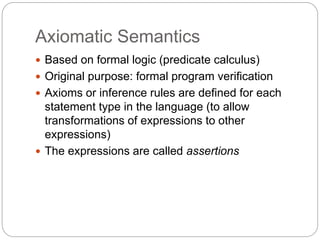

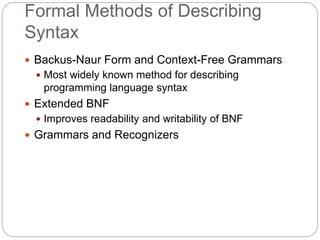

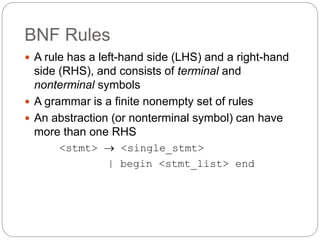

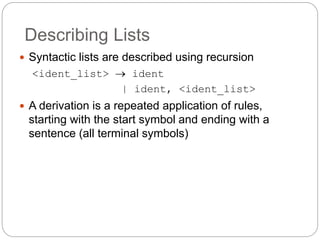

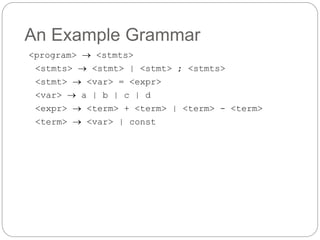

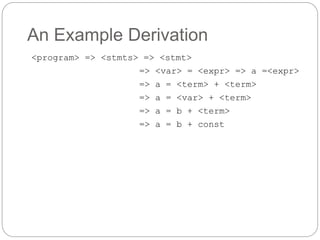

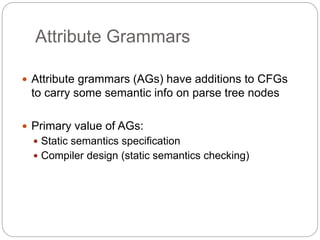

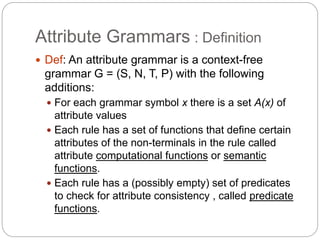

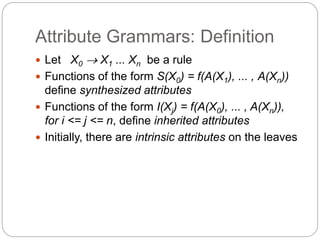

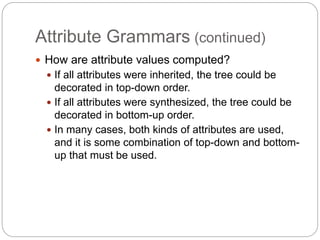

Chapter 3 discusses the syntax and semantics of programming languages, focusing on methods for defining them, such as Backus-Naur Form and attribute grammars. It describes the formal structure of languages, including lexemes, tokens, and how expressions can be derived, along with the importance of operational, denotational, and axiomatic semantics. This chapter serves as a foundational reference for understanding the rules and structures that govern programming language design and implementation.

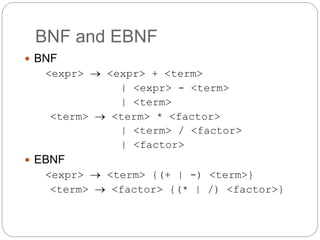

![Extended BNF

1-20

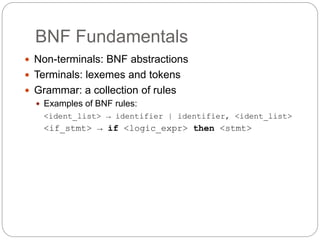

Optional parts are placed in brackets [ ]

<proc_call> -> ident [(<expr_list>)]

Alternative parts of RHSs are placed inside

parentheses and separated via vertical bars

<term> → <term> (+|-) const

Repetitions (0 or more) are placed inside braces {

}

<ident> → letter {letter|digit}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch03-240716122855-a33399ca/85/Describing-syntax-and-semantics66666-ppt-20-320.jpg)

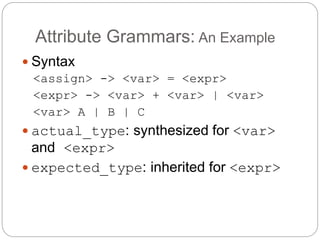

![Attribute Grammar (continued)

1-27

Syntax rule: <expr> <var>[1] + <var>[2]

Semantic rules:

<expr>.actual_type

<var>[1].actual_type

Predicate:

<var>[1].actual_type == <var>[2].actual_type

<expr>.expected_type == <expr>.actual_type

Syntax rule: <var> id

Semantic rule:

<var>.actual_type lookup

(<var>.string)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch03-240716122855-a33399ca/85/Describing-syntax-and-semantics66666-ppt-27-320.jpg)

![Attribute Grammars (continued)

1-29

<expr>.expected_type inherited from parent

<var>[1].actual_type lookup (A)

<var>[2].actual_type lookup (B)

<var>[1].actual_type =? <var>[2].actual_type

<expr>.actual_type <var>[1].actual_type

<expr>.actual_type =? <expr>.expected_type](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch03-240716122855-a33399ca/85/Describing-syntax-and-semantics66666-ppt-29-320.jpg)