This document presents a project book on designing DCMPL logic circuits in a 28nm process technology. It was authored by Itamar Greenberg and Shay Rubinstein from the Department of Electrical Engineering at Bar Ilan University. The document includes an introduction to CMOS scaling challenges, a literature survey of logic families such as diode logic, RTL, TTL, NMOS, PMOS and CMOS. It describes the design, modeling, layout and simulation of various digital logic gates including NOR3, NOR4, OR3 and OR4 gates. Simulation results on propagation delay, energy consumption, voltage transfer curves and noise margins are presented and analyzed.

![CHAPTER

1

INTRODUCTION

F

or over four decades scientists have been scaling increasingly smaller devices trying to

maintain the "MOORE" law. This trend caused by unending demand for high performance

appliances such as laptops, cellphones, and "IOT"-internet of things. Another challenge

these days is dealing with growing competition between the chip design companies. No matter

how the future of the VLSI world will look like one steady rule will stay: It is impossible to

improve power consumption, performance, and area of the chip at the same time. Or in other

words: "there is no free lunch". In this chapter we describe the main issues that concern engineers

dealing with the CMOS unreliability problems in process and integrating IP’s for nanometer

technology. The intent of this chapter is not to give an in-depth description of the failure behind

the problems, but to provide the reader with the basic knowledge of CMOS reliability problems

and how they affect the performance at gate level circuit. First, sec 1.1 outlines how various

unreliability effects came into play in the course of history. Later sec 1.2 we will briefly explain

the mainstream unreliability effects such as spatial unreliability effects and time-dependent

unreliability effects.

1.1 History

The reliability of digital devices was first studied in the 1960’s, when complex integrated systems

were developed for the first time. The most famous conference which brought the physical unre-

liability problem to light was the first international reliability physics symposium (IRPS 1962,

Chicago).

During the 1970’s effects such as ionic contamination and corrosion were the most common causes

of circuit failure. During the 1980’s integrated reliability issues became visible. Further scaling

of the oxide thickness had increased the electrical field between the gate and the bulk, which

creates the hot carries injection phenomenons that eventually harm the gate performance.

Initially, arbitrary voltage stress resulted in an identical parameter shift for matched devices [5].

So at the beginning this kind of unreliability effects were considered as deterministic problems.

However, when oxide dielectrics reached the atomic- scale dimension, it resulted in the first

stochastic temporal unreliability effect. In the late 1980’s when the dimensions of the devices

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-7-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Figure 1.1: CMOS parameters during scaling. Figure reproduced from [? ].

had scaled to the nanometeric realm, stochastic errors and variations at the atomic level became

apparent at device level and sensitive analog circuits were the first to suffer from process vari-

ability effects (Lakshmi Kumar et al. 1986; Pelgrom et al. 1989).

Device mismatch became a big issue (especially analog) designers had to deal with in order to

guarantee good accuracy and high yield.

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-8-320.jpg)

![2.1. LOGIC FAMILIES

The same principles will apply for a NOR gate, as seen in figure 2.3. This time if any of the

input rises to ’1’ then the corresponding transistor will conduct, which will result in the output

discharging.

Figure 2.3: RTL NOR3 logic gate.

The obvious disadvantage of RTL is its high power dissipation when the transistor is switched

on (the power is dissipated mainly by the base resistors connected to logical "1" and by the

collector resistor). This requires that more current be supplied to and heat be removed from RTL

circuits [2].

Transistor-Transistor Logic

Invented in 1961, The TTL family uses transistors to implement the logic function and to amplify

the signal.

A TTL NAND gate is implemented in figure 2.4. When the two emitters of the input transistors

are connected to high voltage, then the emitter-base junction of the transistor is reverse biased,

that means the transistor is in reverse active mode. In reverse active mode, less magnitude

current flows in the opposite direction. This current reaches the base of the output transistor,

allowing it to conduct and pulling down the output voltage to zero. When any one of the input

terminal is low, the current through other branch flows out through this terminal. Now no current

reaches the base terminal of the output transistor, so output remains at high state [4].

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-11-320.jpg)

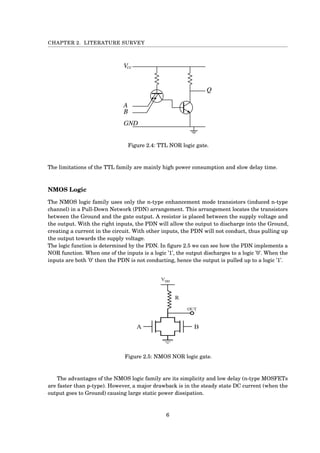

![2.1. LOGIC FAMILIES

The PMOS logic family is similar to NMOS, except it uses p-type transistors and places them

at the Pull-Up Network (PUN) and a resistor attached to Ground.

Pass Transistor Logic

Up until now we saw logic families with transistors connected to supply/Ground voltages at

one end. The PTL family uses transistors as switches to pass logic levels between nodes of a

circuit, without these transistors being connected to a supply voltage. This feature can reduce the

number of transistors used to implement a logic function by eliminating redundant transistors.

PTL comes extremely handy when producing complicated gates and memory cells like Multiplex-

ers, Flip-Flops and SRAM. Figure 2.6 shows a PTL Multiplexer using only two transistors. The

implementation is very simple to understand [3].

Figure 2.6: PTL MUX gate uses only two transistors

However, we notice that the NMOS transistors will pass a weak ’1’. To avoid that, we use a

transmission gate as seen in figure 2.7. The PMOS transistor passes a strong ’1’ and the NMOS

transistor passes a strong ’0’.

Figure 2.7: Transmission gate

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-13-320.jpg)

![CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE SURVEY

Complimentary MOS Logic

The CMOS family is a combination between the NMOS and PMOS families. The PDN consists of

n-type transistors and the PUN consists of p-type transistors. In that case, both the PDN and the

PUN have to implement the logic function.

Figure 2.8 shows the design of a NAND and NOR logic gates. We can see the relation between

the PDN and the PUN in a given CMOS gate. If the PDN has a parallel formation then the PUN

has a serial formation, and vise-versa.

Figure 2.8: CMOS NAND and NOR logic gates.

The CMOS design has managed to achieve great improvements in numerous parameters,

reaching characteristics of almost an ideal logic family. [1]

First, the static power dissipation decreases dramatically. Unlike the NMOS/PMOS logic

families, there will never be a straight path between the supply voltage and the Ground. This is a

result of the relation between the PDN and the PUN which are always complimentary, meaning

that when one is conducting the other is not. The static power dissipation is caused only by

leakage currents. These currents are more significant as the device is scaled.

Secondly, the propagation delay is rather short for both networks, though the NMOS is faster

than PMOS. In order to make both networks equal in respect to propagation delay time we use

wider p-type transistors in the PUN. The ratio between the widths of the n-type and the p-type

transistors is represented by "Œ ≤". The Œ ≤ parameter depends on the technology we are using.

Third, the rise and fall times are controlled by the sizing of the transistors. Last is the noise

margin. Ideally we want a noise margin of 50%. the supply voltage. The CMOS noise margin is

reaching values close to the ideal.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-14-320.jpg)

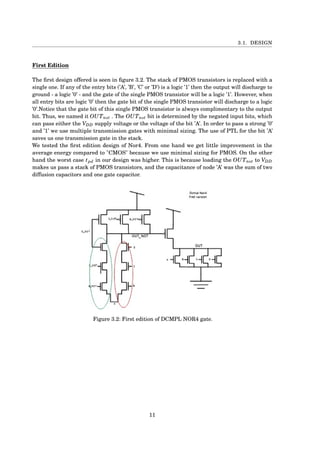

![3.2. MODELING

3.2 Modeling

In this chapter we aim to develop a mathematical model that anticipates the tpd and Energy of

the DCMPL logic gate for any given gate capacitance.

Power Consumption

Power Consumption of any circuit is divided into the following categories:

• Dynamic power ∼ Cload · vdd2

• static power ∼ Istatic · vdd

• short circuit power ∼ Tsc · Ipeek · vdd · f

We modeled the load capacitance which is critical for predicting the dynamic power when charging

the output of the gate. We ignore the voltage supply effect because the simulation uses each time

the same VDD . In order to find Cload we have to find all capacitance which connect directly to

wire OUT and OUTnot in both design.

In the CMOS design figure [a] the ’OUT’ wire connect to three Cdif f of the NMOS transistors,

one Cdif f of the PMOS transistor multiply by β, and the capacitance gate of the next stage.

In the DCMPL design figure [b] the ’OUT’ wire connect to three Cdif f of the NMOS transistors,

one Cdif f of the PMOS transistor, and the capacitance gate of the next stage.

more over the OUTnot wire connect to three Cdif f of the PMOS transistors, one Cdif f of the

NMOS transistor, and the capacitance gate of INPUTnot of the next stage.

CMOS MODEL:

NOR3

N-number of inputs.

β-sizing of the pull up transistors in CMOS.

CgA|B|C = β·C +C = 4.9C.

Cout = β·CPdif f + N ·CNdif f +Cnexts tage =

3.9·CPdif f +3·CNdif f +CPgate +CNgate =

3.9C +3C +3.9C + c = 11.8C

NOR4

N-number of inputs.

β-sizing of the pull up transistors in CMOS.

CgA|B|C = β·C +C = 6.2C.

Cout = β·CPdif f + N ·CNdif f +Cnexts tage =

5.2·CPdif f +4·CNdif f +CPgate +CNgate =

5.2C +3C +5.2C + c = 14.4C

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-21-320.jpg)

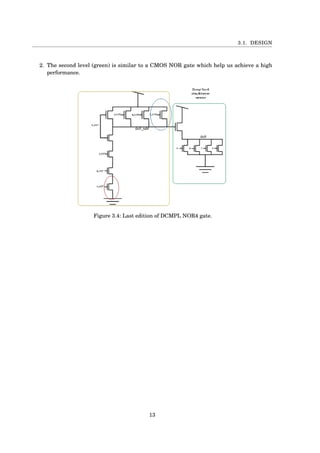

![CHAPTER 3. DESIGN AND SIMULATION

Tpd - Elmore Delay

We use the Elmore-Delay in order to model the delay of the gate through the worst case vector by

charging and discharging the output.

In each one of the design we find the total capacitance and resistance go through transistors from

input to output.

At last we modeled how the trend line of tpd vs VDD should look like.

First we find who is the longest vector[fig3.7]. The vector who has to pass more capacitance on

the way is tplh(out) form input A.

Second we use Elmore-Delay model find how many capacitance and resistance on the critical

path so the general equation for unknown β and inputs is:

Third we know from VLSI course (assuming Cdif f const) that:

We subtitute R,C,S,β in the equation above and find that: tpd graph ∼ const· 1

V dd

In Summery we expect the tpd vs VDD will act like 1

x graph.

Figure 3.7: Charging OUT to VDD by different inputs in Nor4 gate

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-24-320.jpg)

![3.3. LAYOUT

3.3 Layout

The layout stage is where we simulate the physical layers of our digital gate.

This is an importent stage since all the properties of our gate derive from it.

Due to the secrecy of the 28 nm proecess we can not show any photos of our layout, however we

will discuss some principles and challenges we encountered during the project as can be seen in

figure 3.8.

The first challenge was the limitation on breaking the polysilicon. furthermore the gap between

polysilicon layers must be constnt [1].

Secondly, minimizing the distance between diffusion layer is limited due to several design rules[2].

third, metal thickness often needs to increase significantly[3].

Figure 3.8: Layout Challenges in 28 nm

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-25-320.jpg)

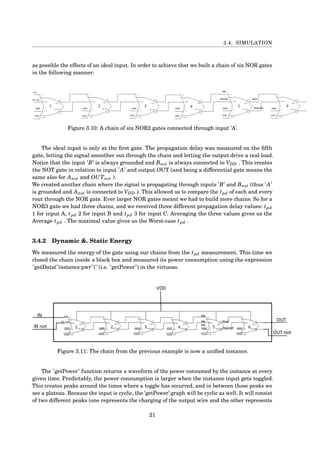

![CHAPTER 3. DESIGN AND SIMULATION

3.4.3 "SNM"- Static Noise Margin

The "SNM" analysis is taken from volatile memory cells such as SRAM memory.

We connected two gates as a ring oscillator of two inverters and checked what is the maximum

noise we can add to the input while still keeping a stable data in the cell.

In order to measure the SNM we used transformation circuits to rotate the VTC graph by 45◦

.

Then we ran a DC sweep from -VDD /sqrt(2) to VDD /sqrt(2) on V uaxis and found what is the

maximum diagonal of the square in the right and left side.

And finely, the minimum of the two diagonals will give us the "SNM" measurement.

(a) (b) (c)

(d) (e)

(f)

FIGURE 3.14. (a) A Ring oscillator configuration help to indicate what is max limit of

noise keep the system stable. Figure reproduced from [? ]. (b) Design of the first

transformation function that flip "Y" axis by 45◦

. Figure reproduced from [? ]. (c)

Design of the second transformation function that flip "X" axis by 45◦

.(d) The ideal

of the"snm" simulation is to find the max square in the overlapping area between

two original "VTC" curves.Figure reproduced from [? ]. (e) After we process two

max square from tow different overlapping area we compare between them and

take the minimal square for worst case scenario.Figure reproduced from [? ]. (f)

Summarizing all steps to find static noise margin in any system

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-30-320.jpg)

![BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] R. J. BAKER, CMOS: circuit design, layout, and simulation (Second ed.), Wiley-IEEE,

2008.

[2] IBM, Transistor Component Circuits, IBM.

[3] C. F. H. JAUME SEGURA, CMOS electronics: how it works, how it fails, Wiley-IEEE,

2004.

[4] W. R. B. JR., MECL System Design Handbook 2nd ed., Motorola Semiconductor Prod-

ucts Inc. vi., 1972.

[5] B. SYKES, Why test bonds?, Global SMT & Packaging magazine, (2010).

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9a1e0d8e-e59a-4d22-b9a1-bf4a38f20b86-161117162512/85/DCMPL_PROJECT_BOOK_SHAY_ITAMAR-51-320.jpg)