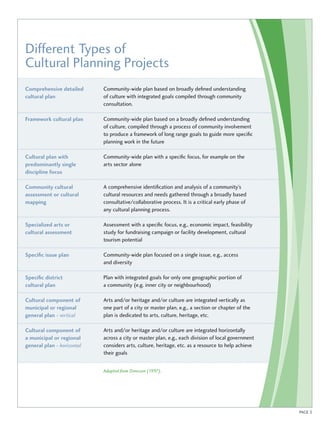

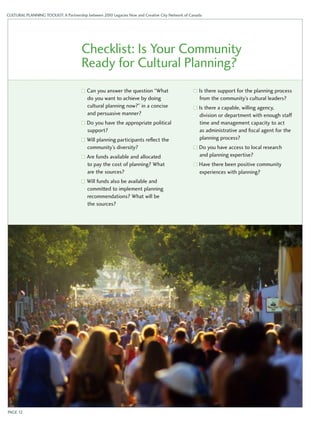

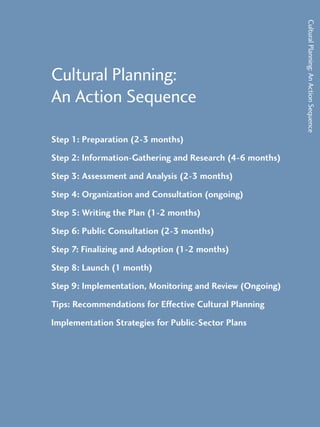

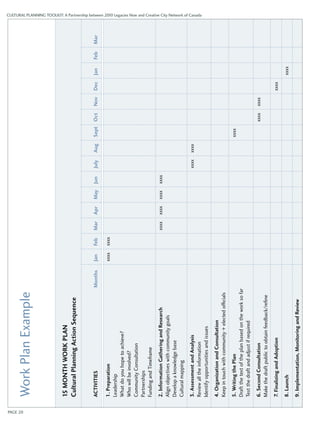

This document provides guidance on cultural planning. It discusses that cultural planning is a process that helps communities identify cultural resources and strategically integrate culture into achieving civic goals. The document recommends several steps to take before starting cultural planning, including reading about cultural planning, asking community members questions to understand local issues, building partnerships, and researching funding. It emphasizes the importance of community consultation and involving a wide range of stakeholders in the cultural planning process.