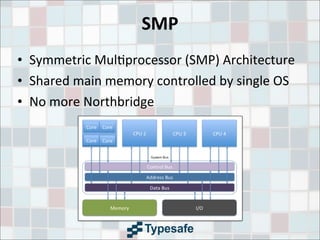

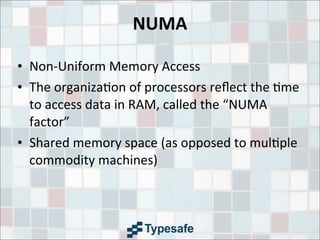

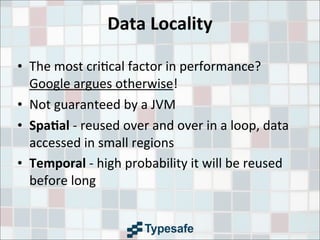

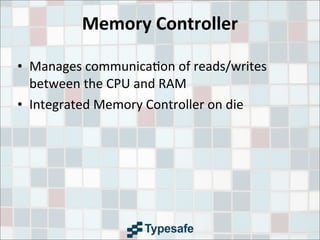

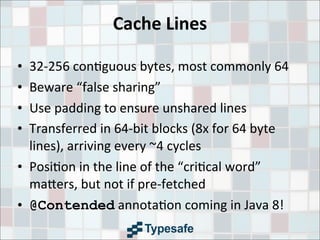

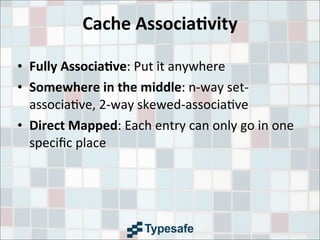

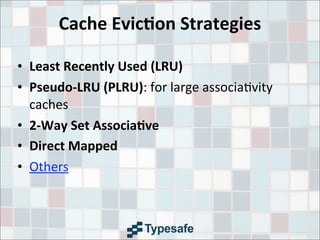

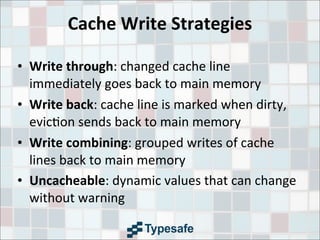

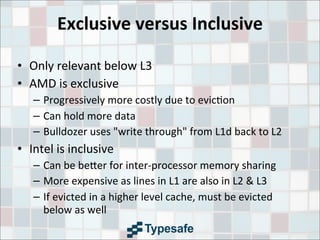

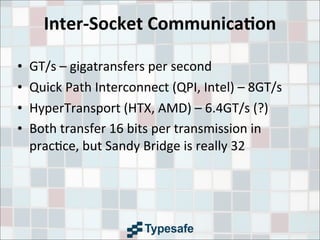

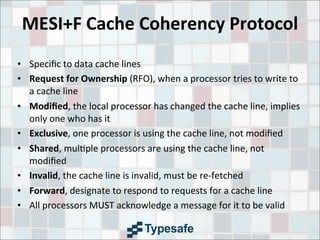

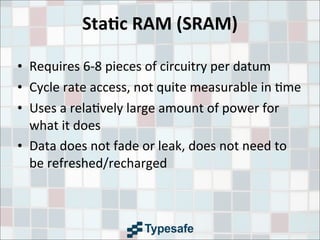

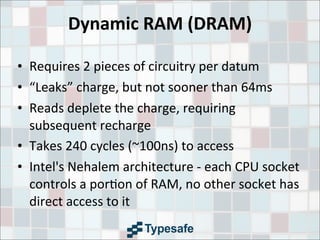

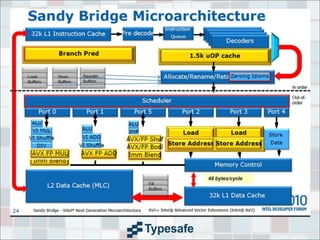

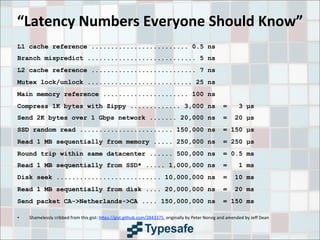

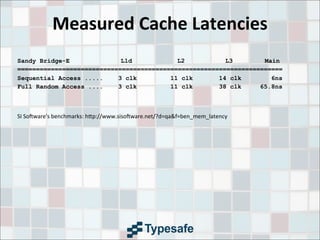

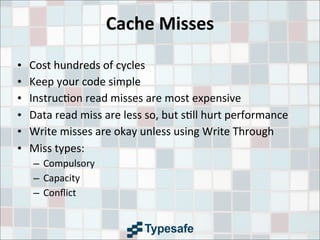

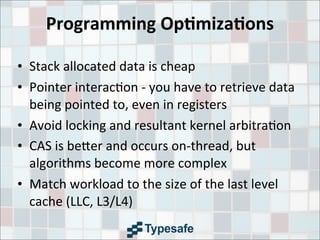

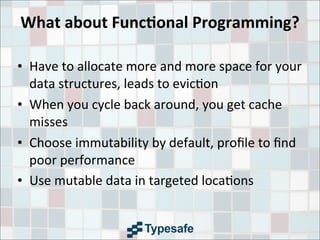

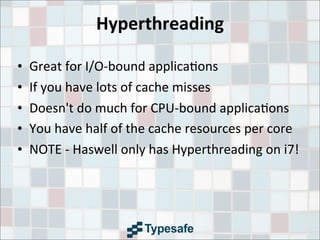

This document provides an overview of CPU caches, including definitions of key terms like SMP, NUMA, data locality, cache lines, and cache architectures. It discusses cache hierarchies, replacement strategies, write policies, inter-socket communication, and cache coherency protocols. Latency numbers for different levels of cache and memory are presented. The goal is to provide information to help improve application performance.