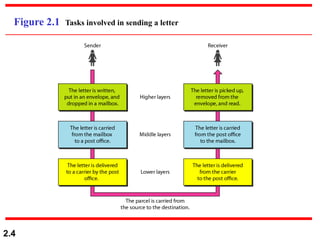

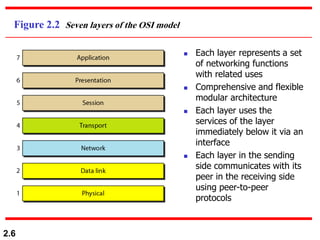

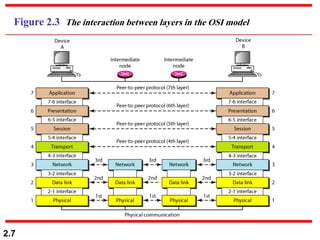

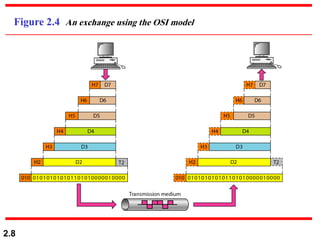

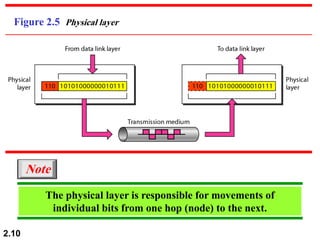

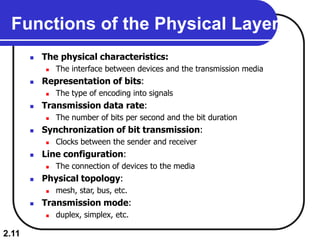

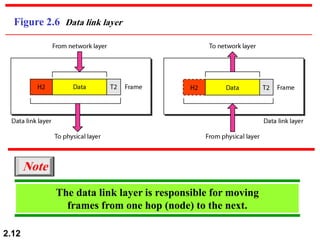

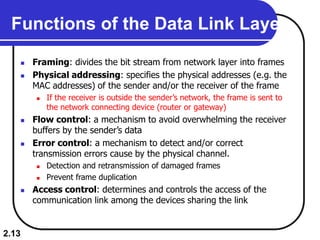

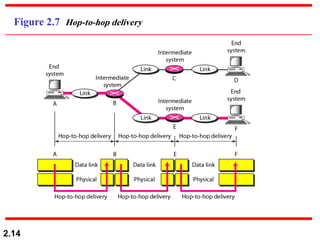

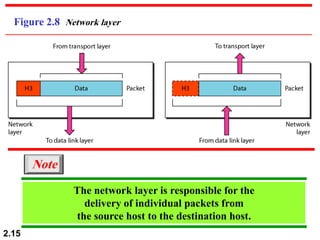

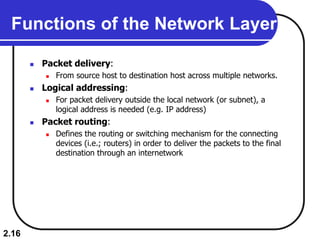

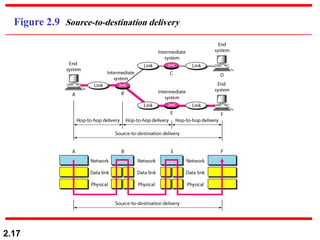

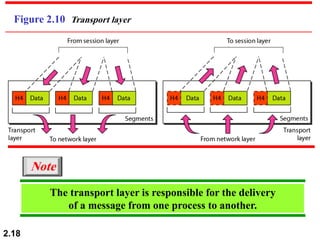

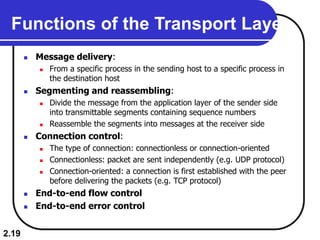

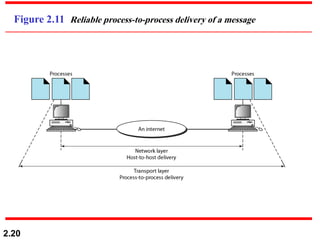

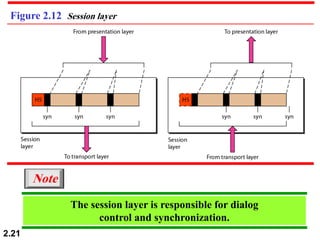

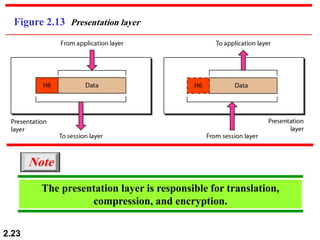

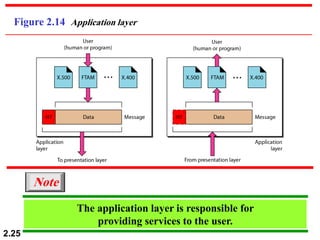

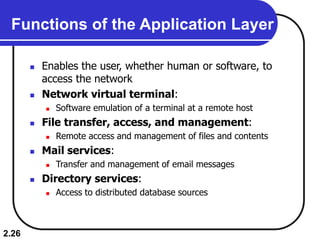

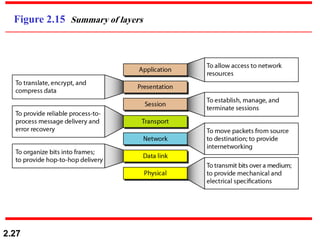

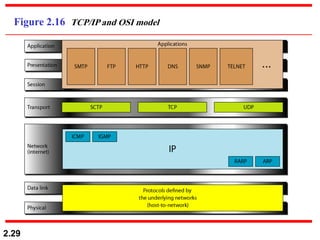

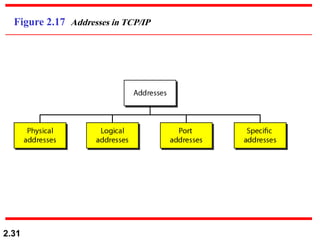

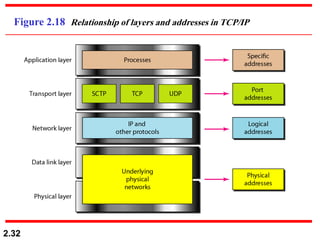

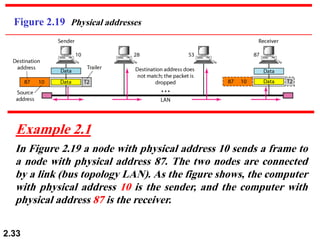

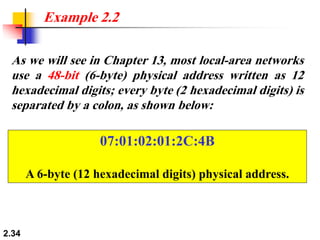

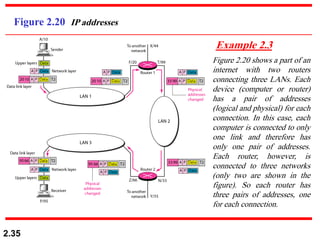

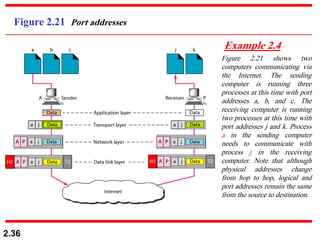

The document describes the OSI model and TCP/IP protocol suite. It discusses the seven layers of the OSI model and the functions of each layer, including the physical, data link, network, transport, session, presentation, and application layers. It also maps the layers of TCP/IP to the OSI model and describes addressing in TCP/IP, including physical, logical, port, and specific addresses.