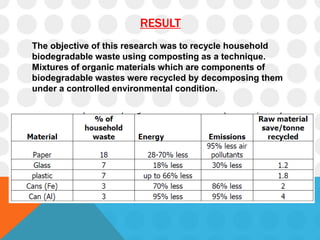

This document provides instructions for making compost from biodegradable waste. It discusses mixing household waste materials like food scraps and yard waste to achieve the proper carbon to nitrogen ratio. The compost was monitored and maintained at optimal moisture and oxygen levels to promote microbial breakdown of materials. The composting process generated heat and resulted in a stabilized organic fertilizer that can be used to supplement soil and support plant growth while reducing waste.