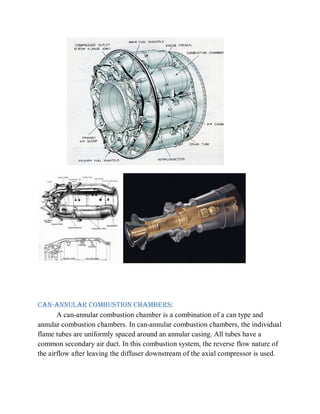

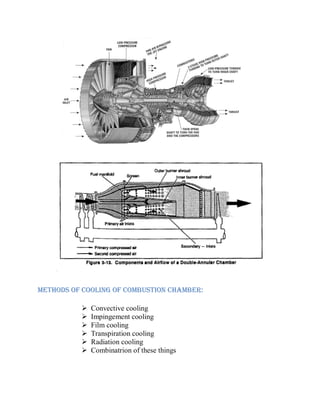

The document discusses combustion chamber design and types for gas turbine engines. It describes the key requirements for combustion chambers including low weight, stable and efficient combustion over operating conditions, and uniform temperature distribution. It classifies combustion chambers as can, can-annular, or annular and describes the characteristics and advantages/disadvantages of each type. Important factors for combustion chamber design are maintaining suitable turbine inlet temperatures, stable combustion over a range of operating conditions, and controlling emissions.