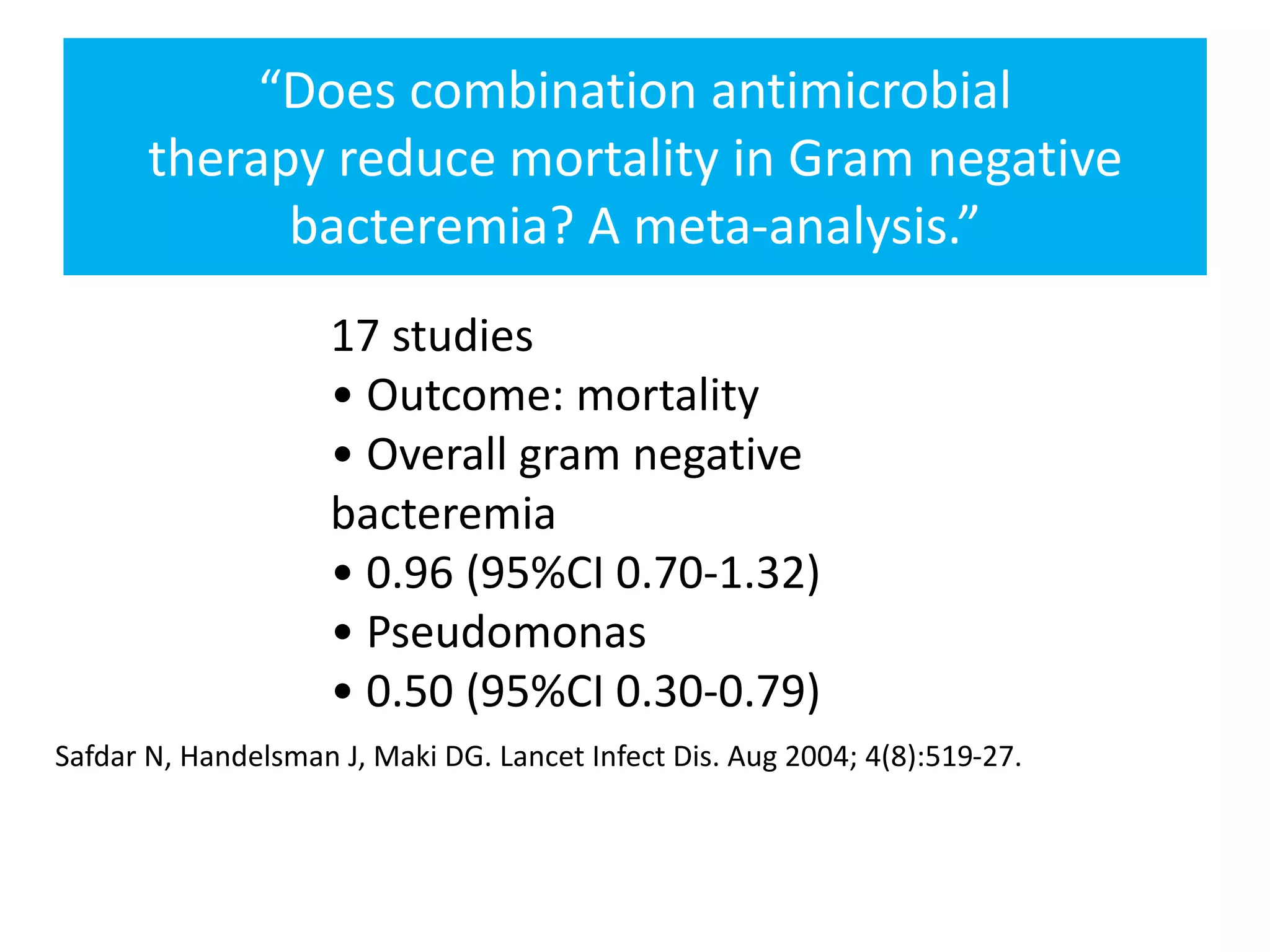

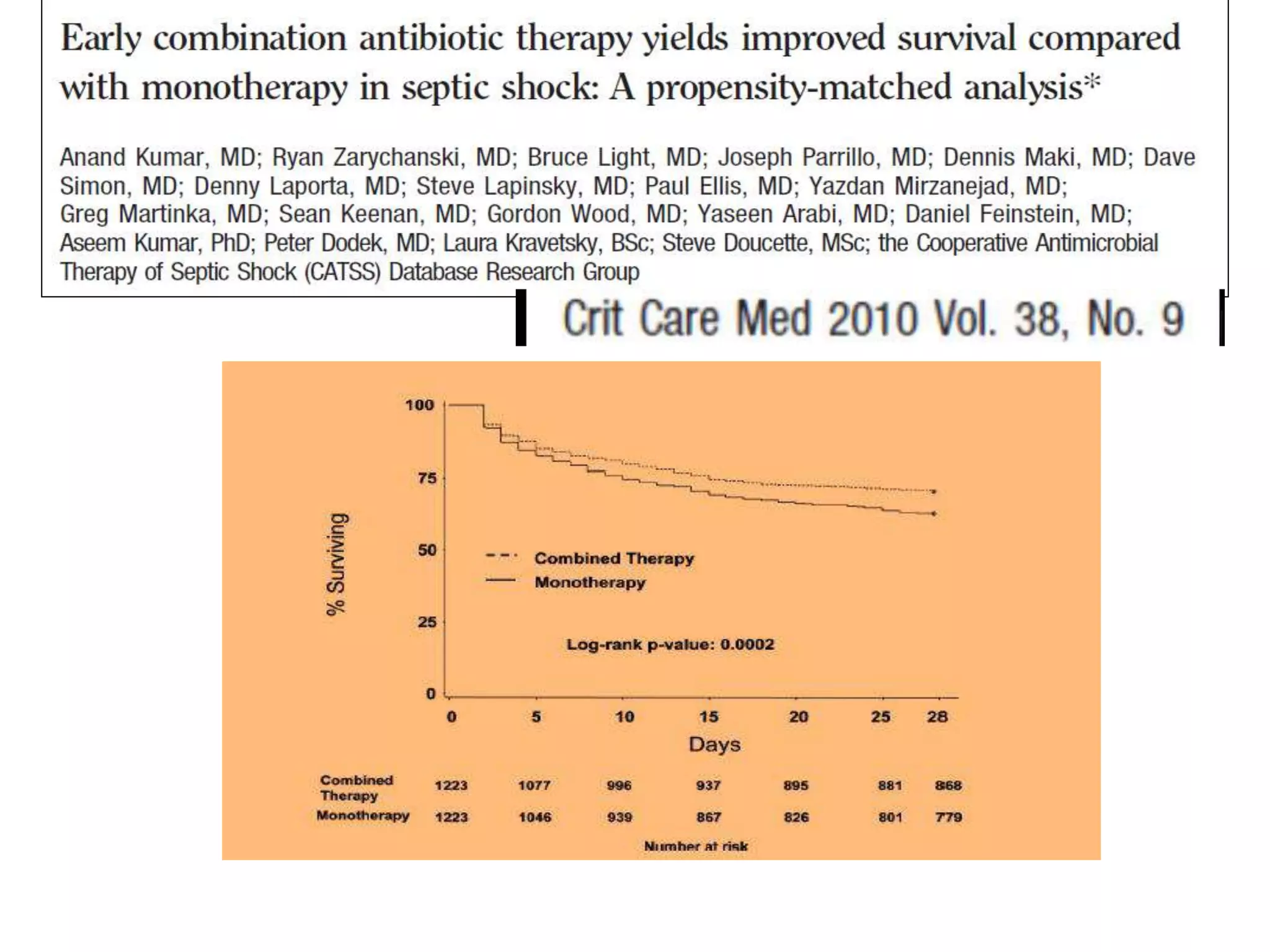

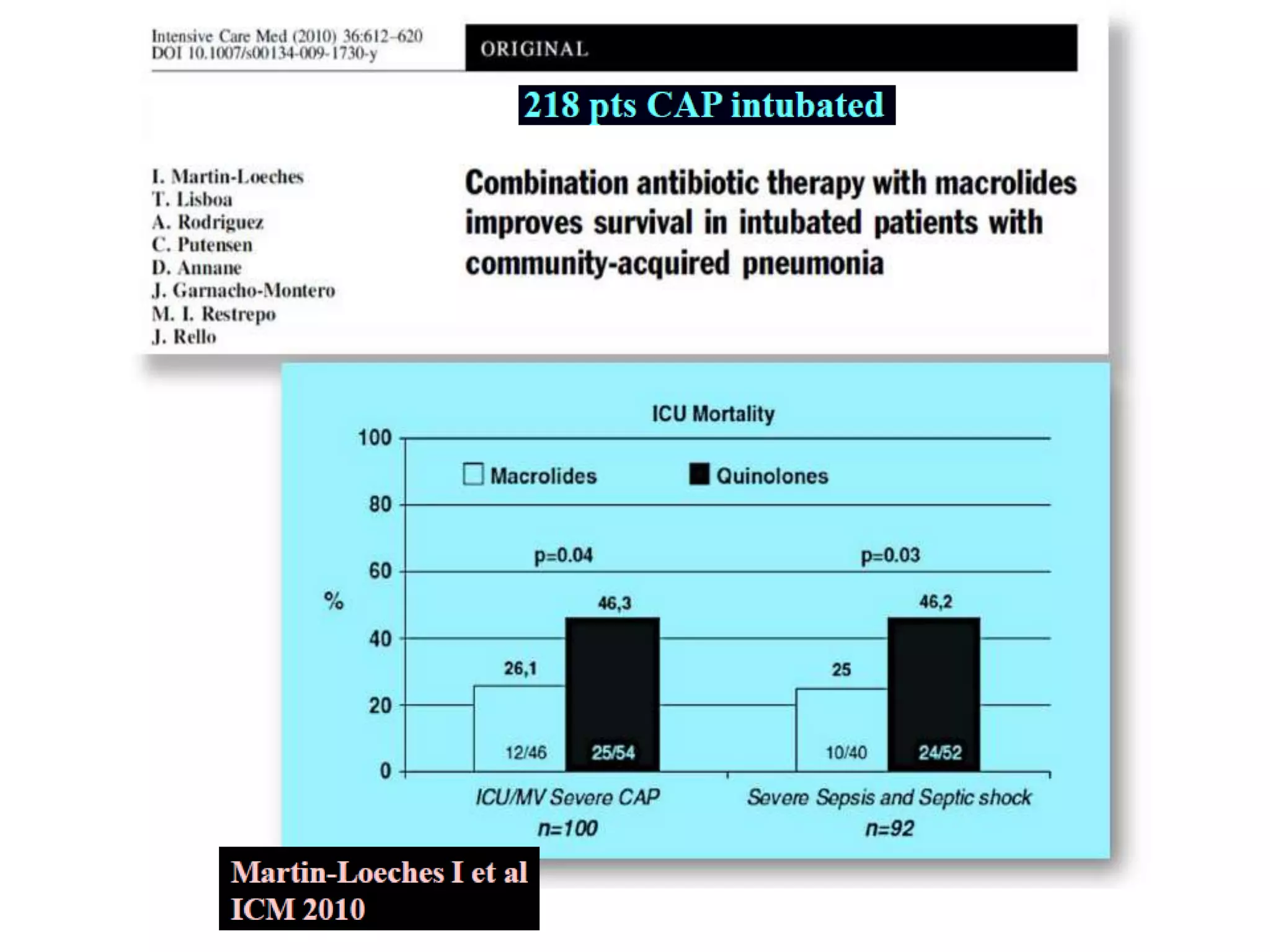

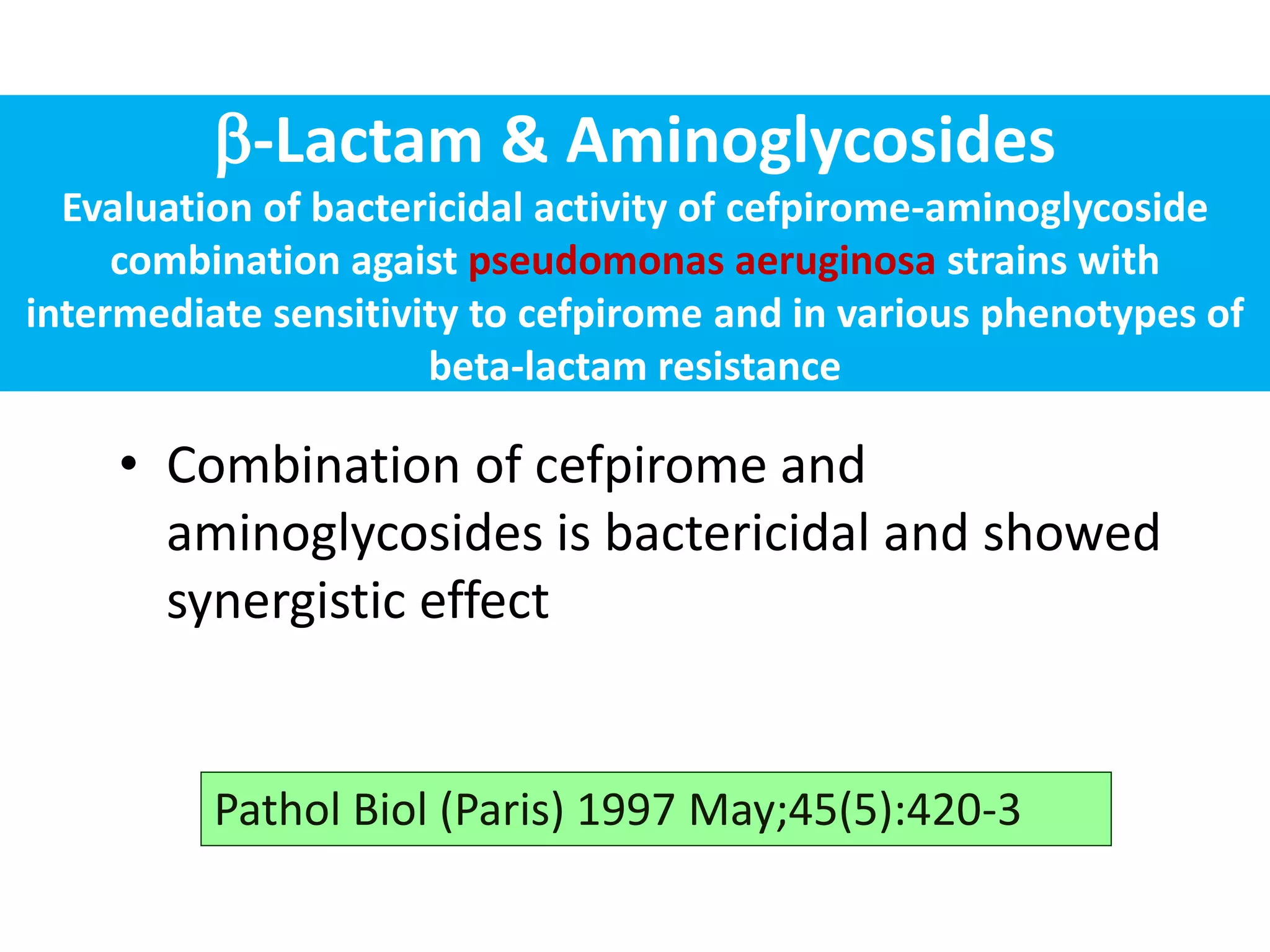

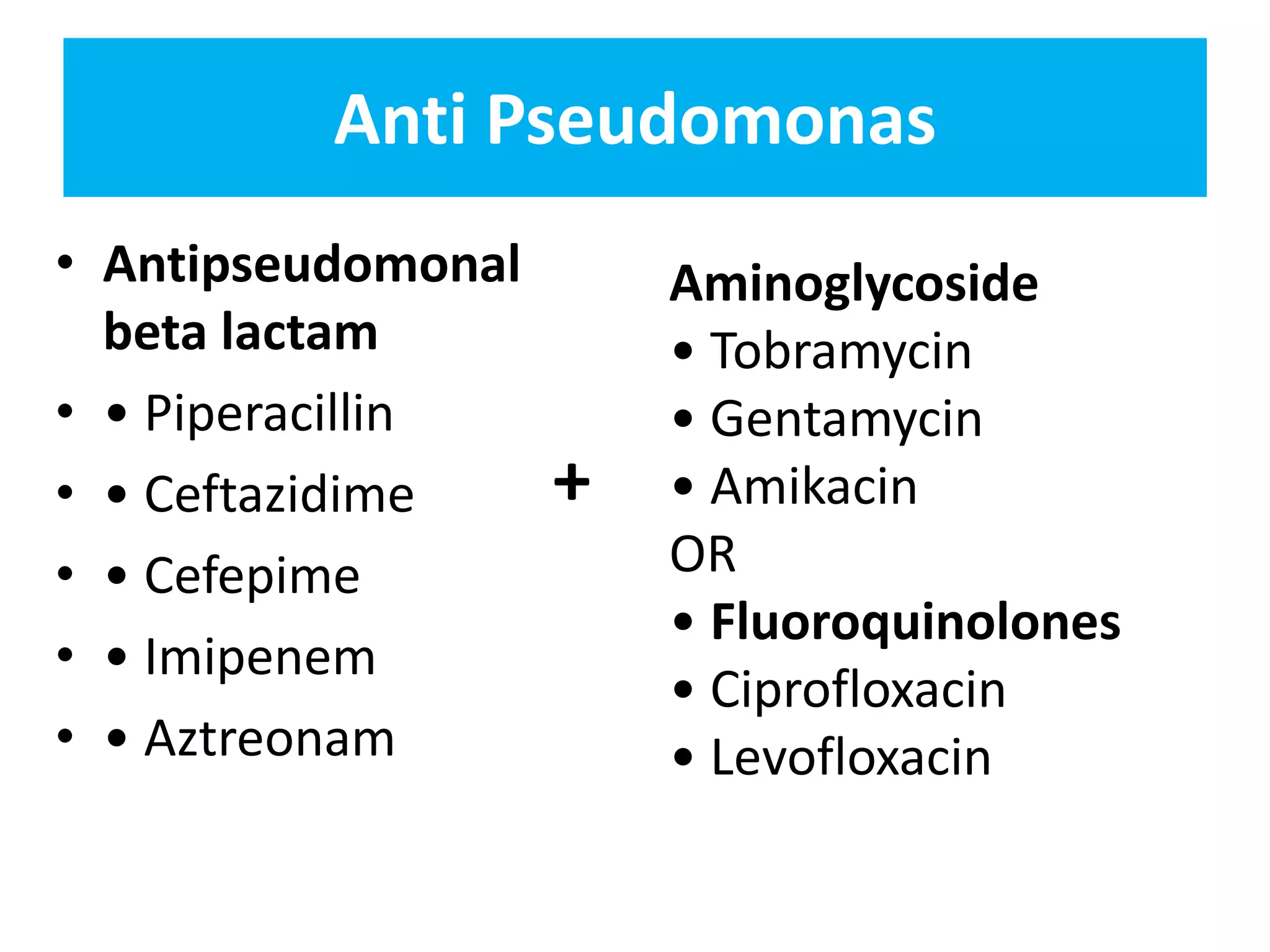

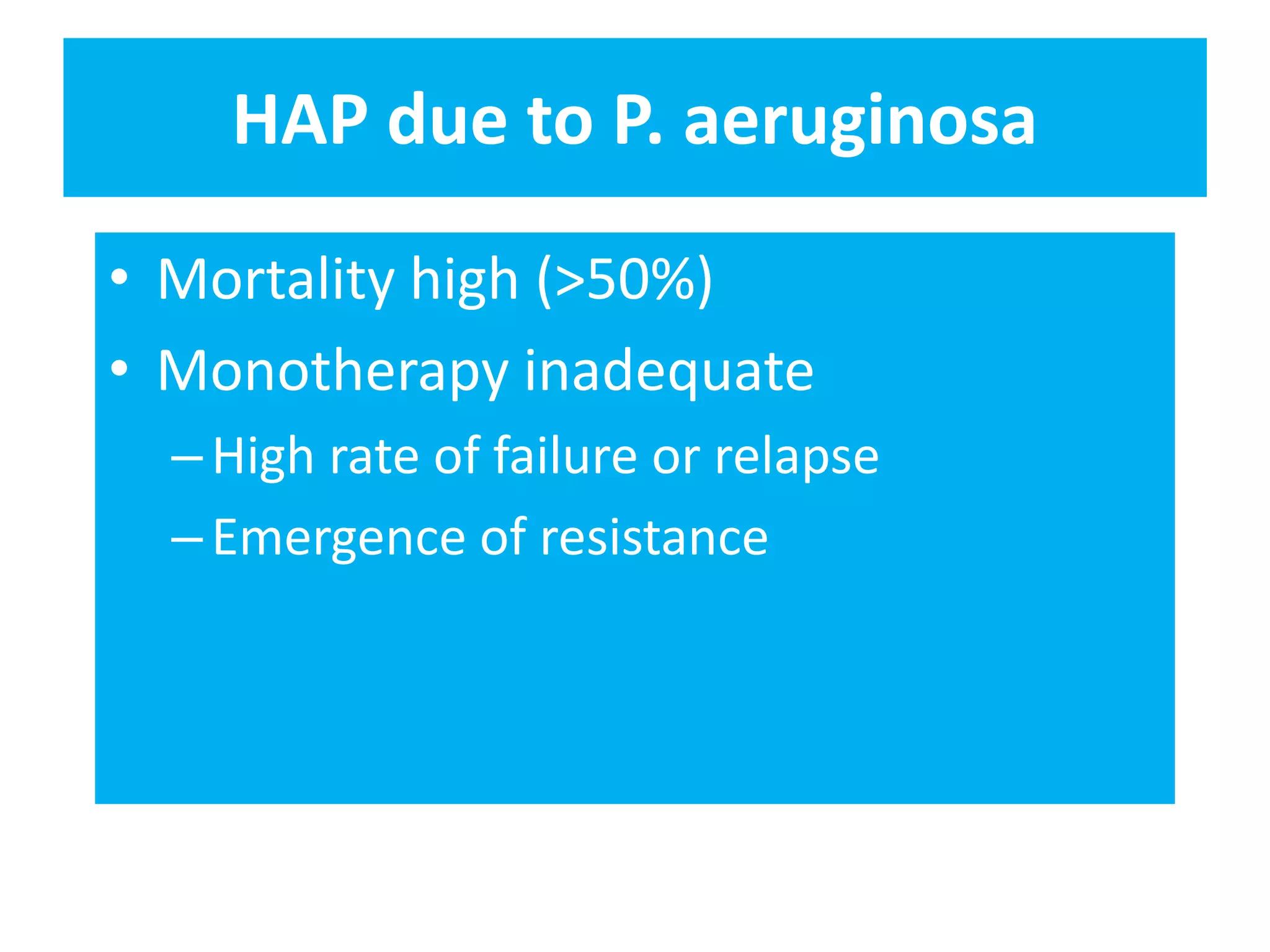

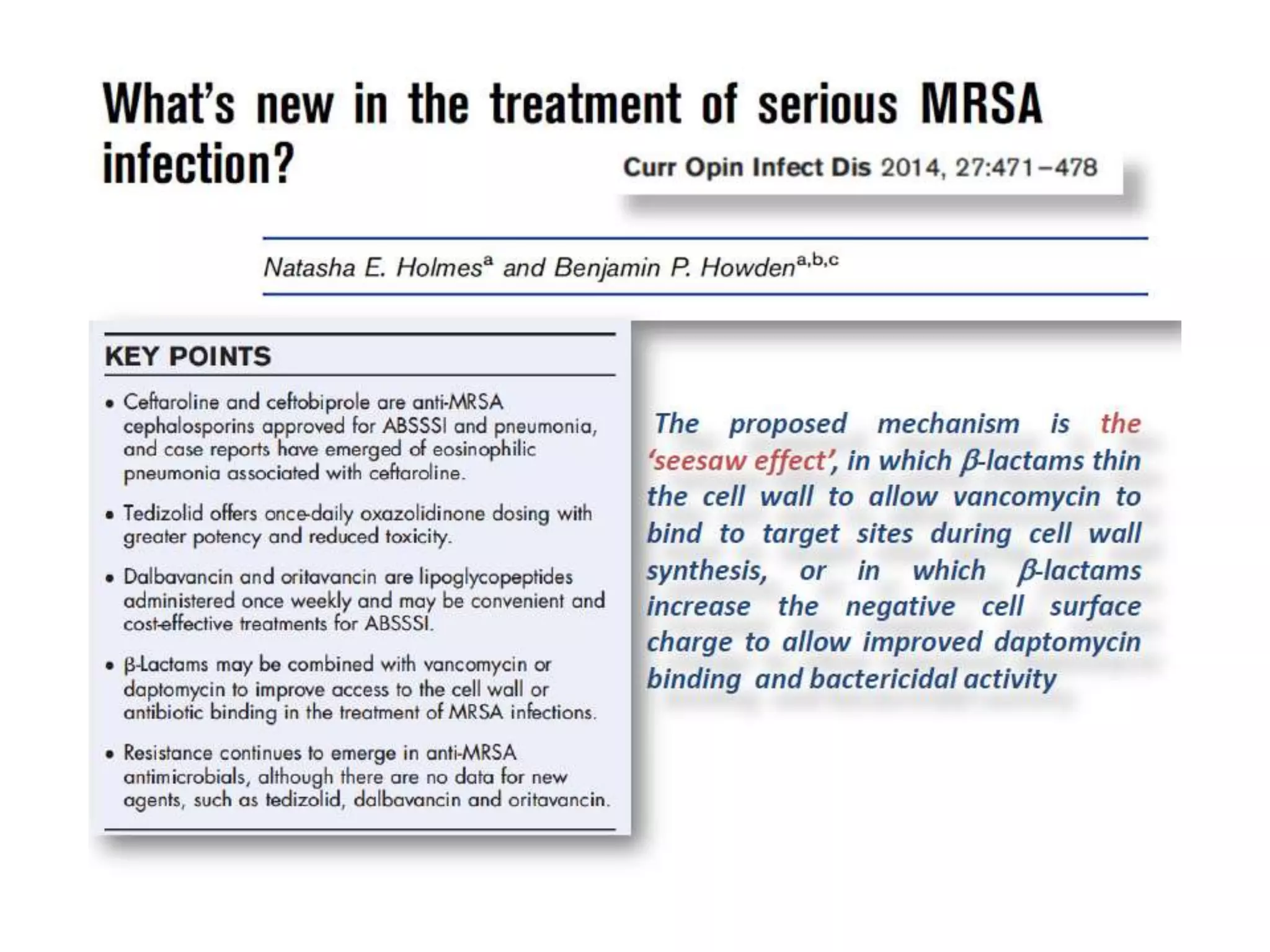

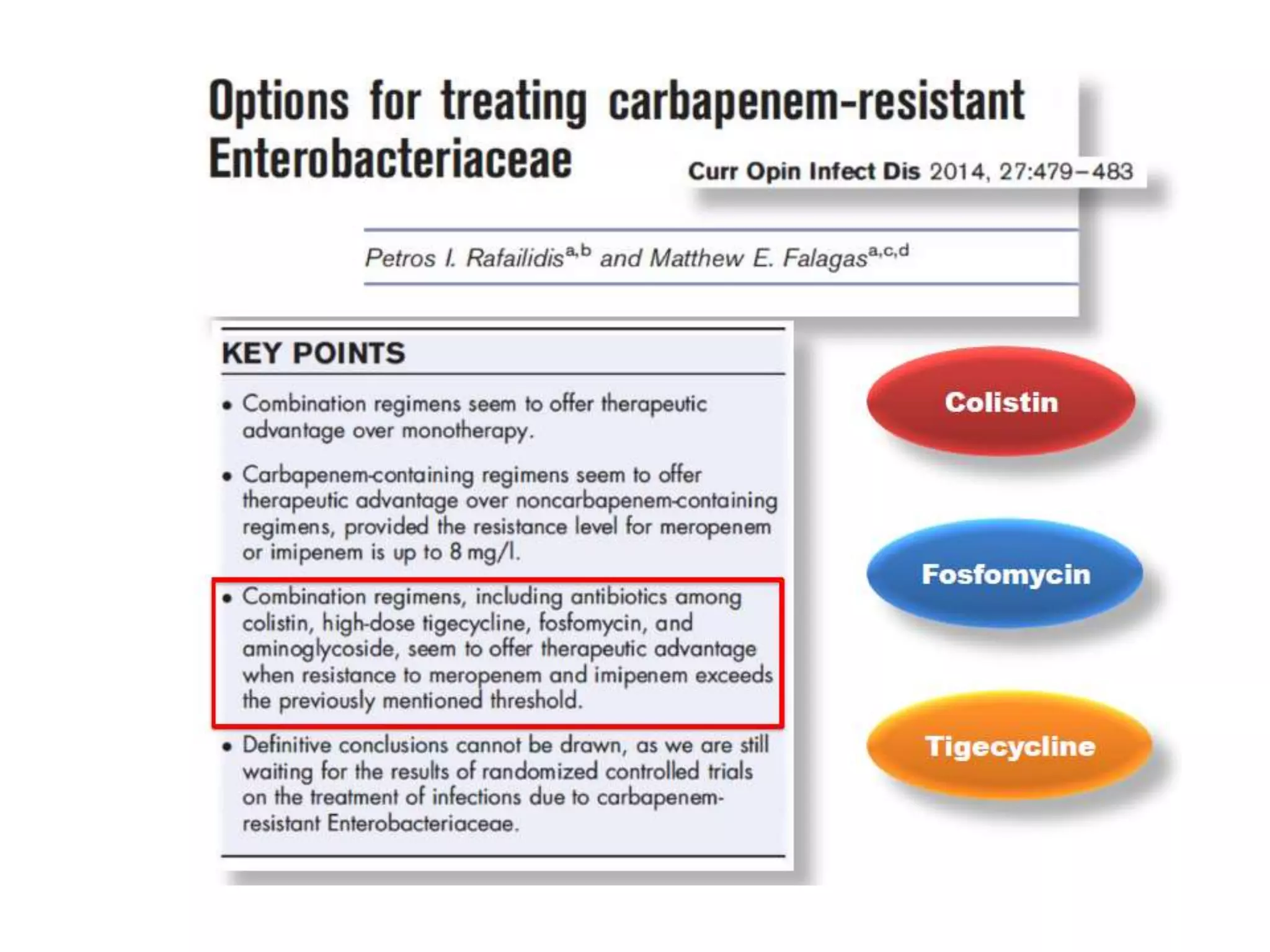

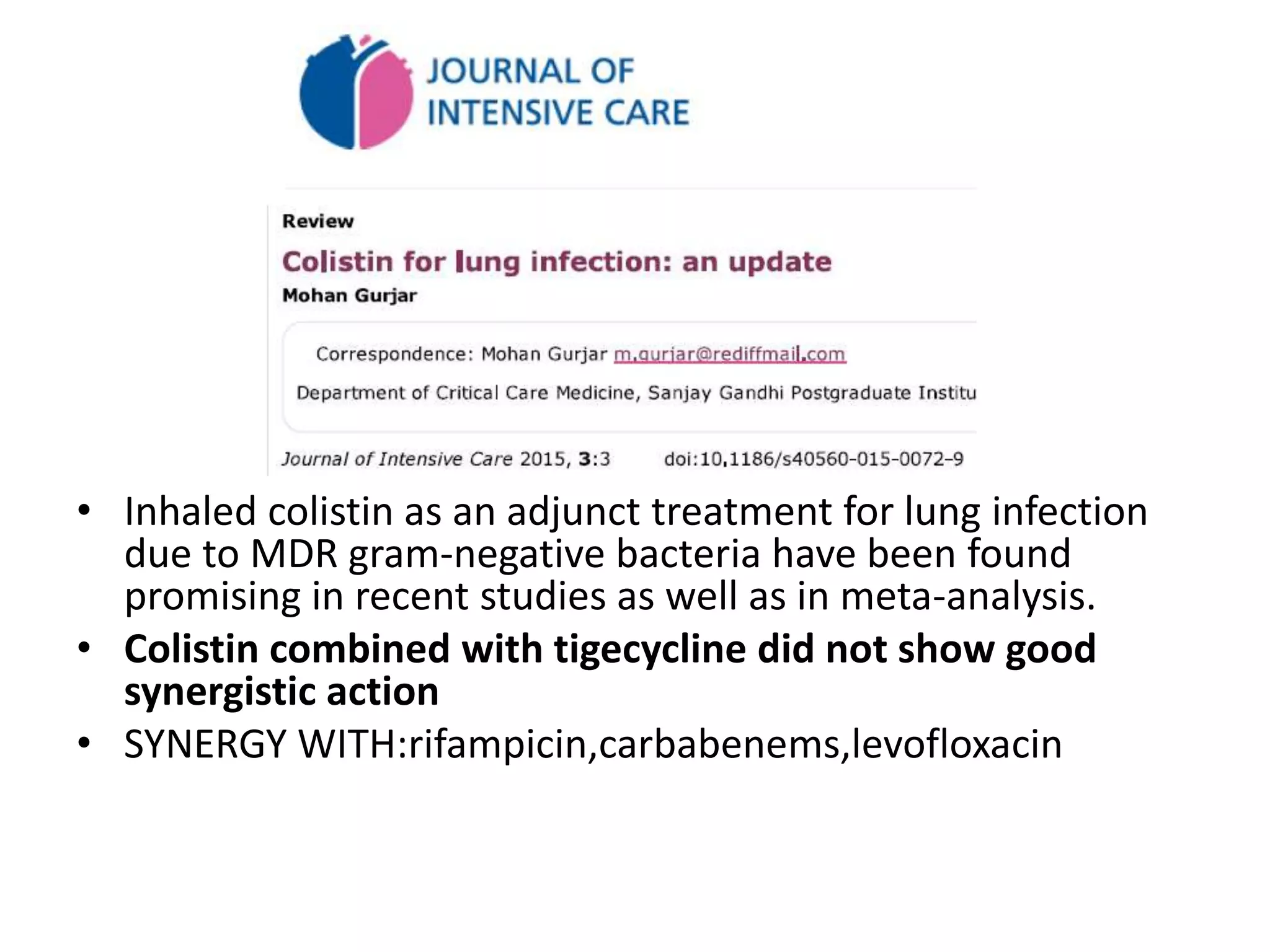

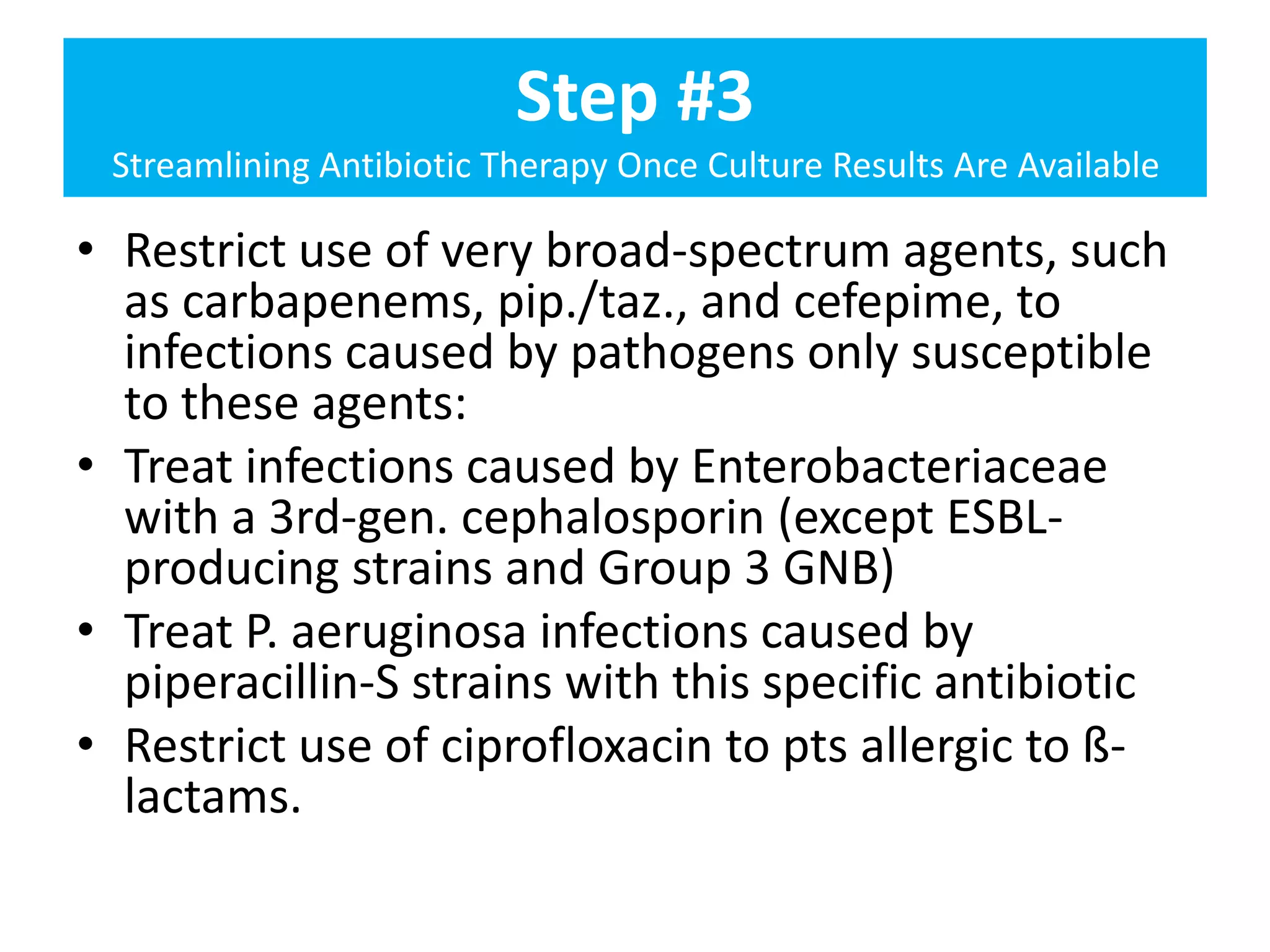

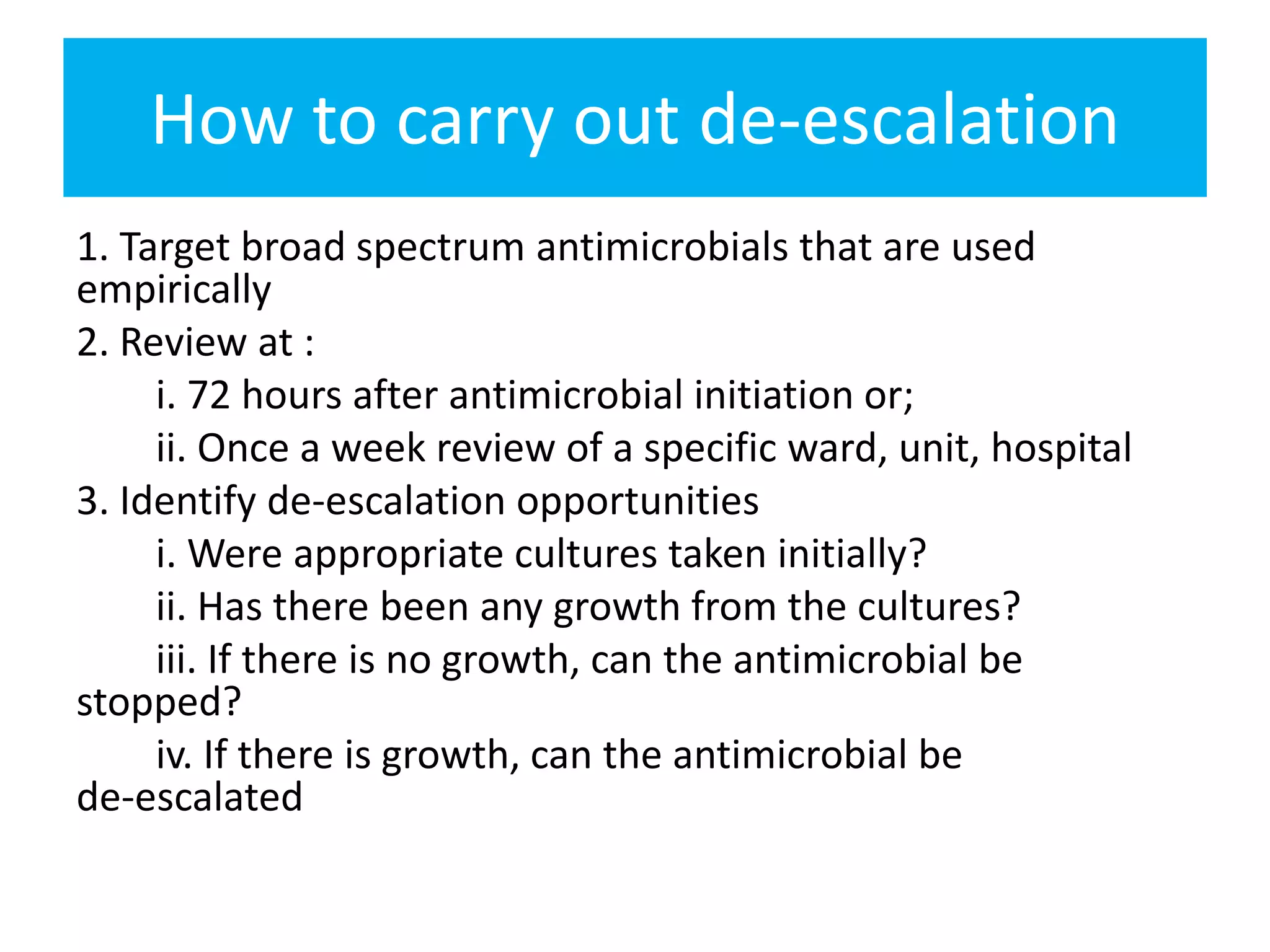

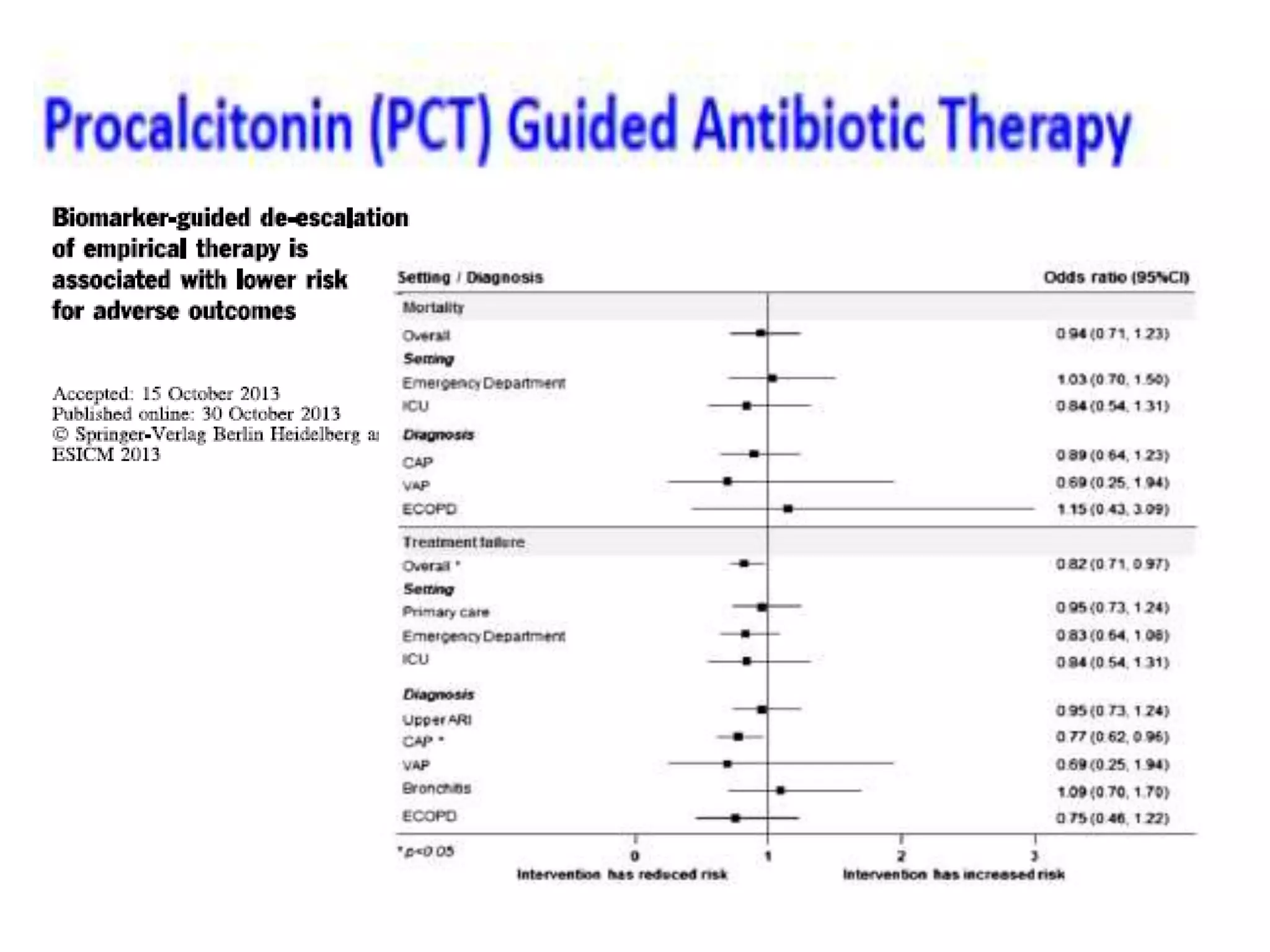

Combination antibiotic therapy can provide benefits over monotherapy in some situations. Combining antibiotics may result in synergistic effects against certain pathogens like MDROs or additive effects. It may help prevent resistance. However, combinations can also lead to antagonism or increased side effects. Appropriate combinations depend on the infection and organism. De-escalation of antibiotics is important for improving outcomes and reducing resistance. It involves narrowing therapy based on culture results and clinical response. Regular review and stopping antibiotics when no longer needed are key aspects of de-escalation.