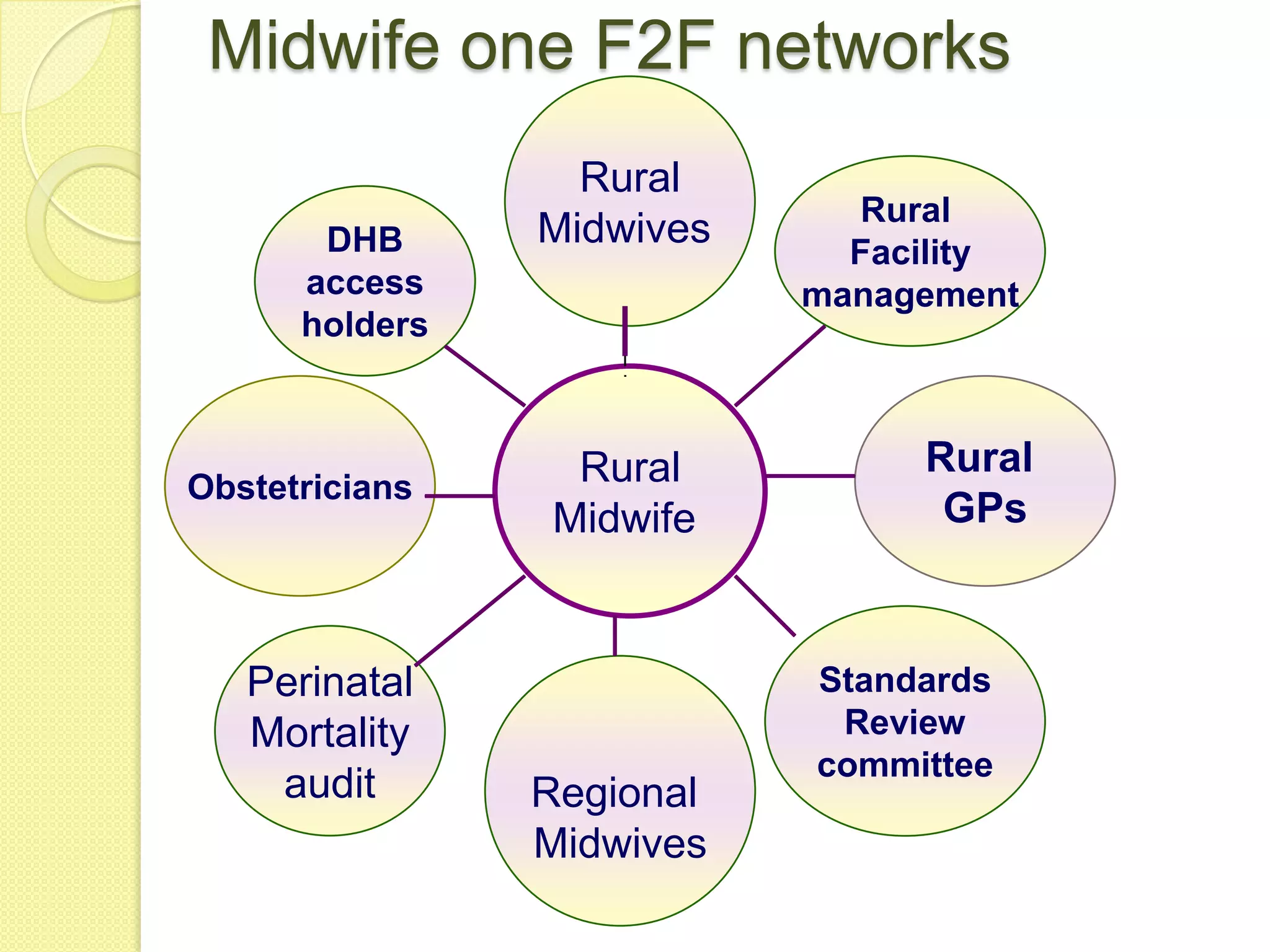

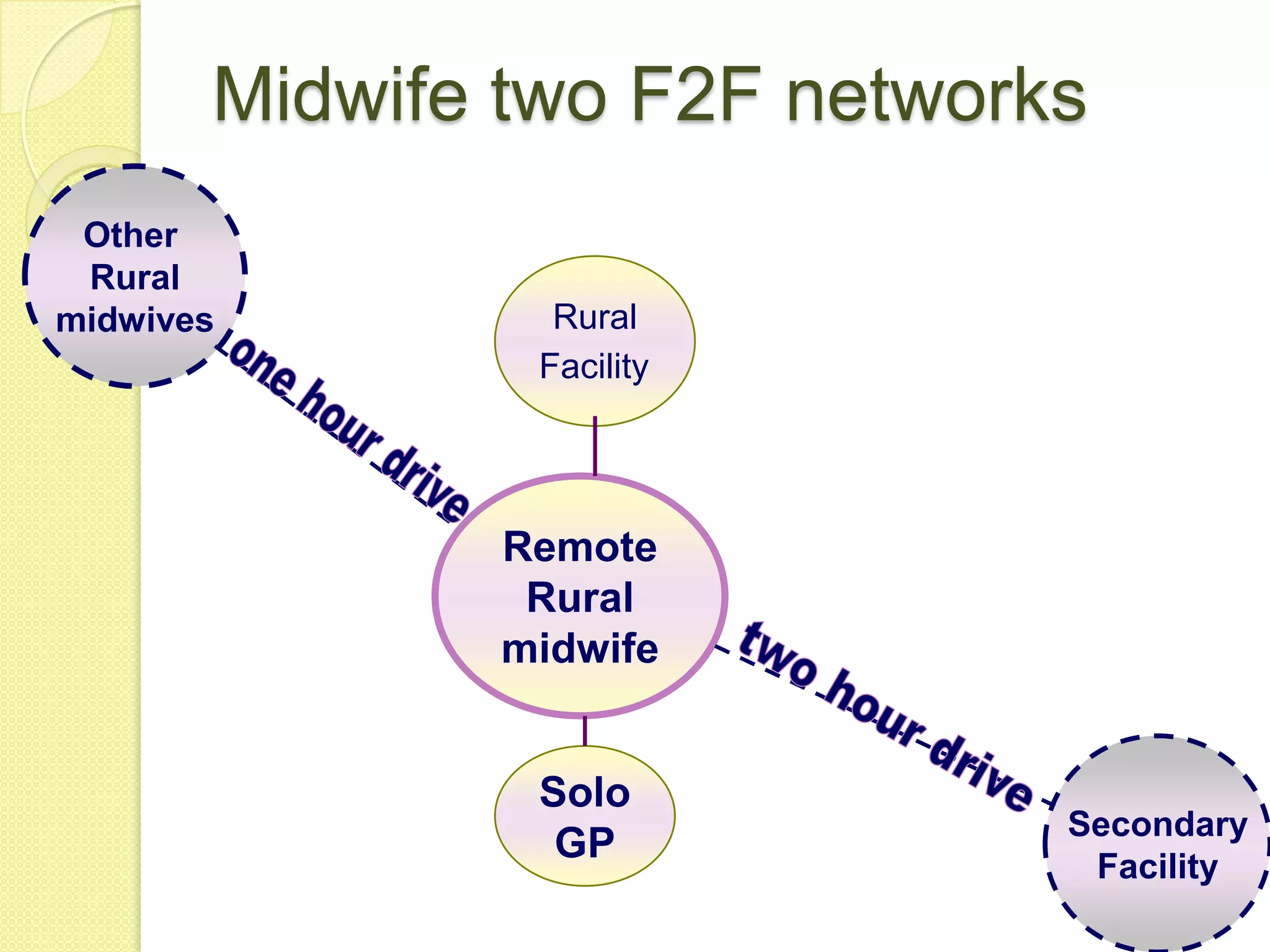

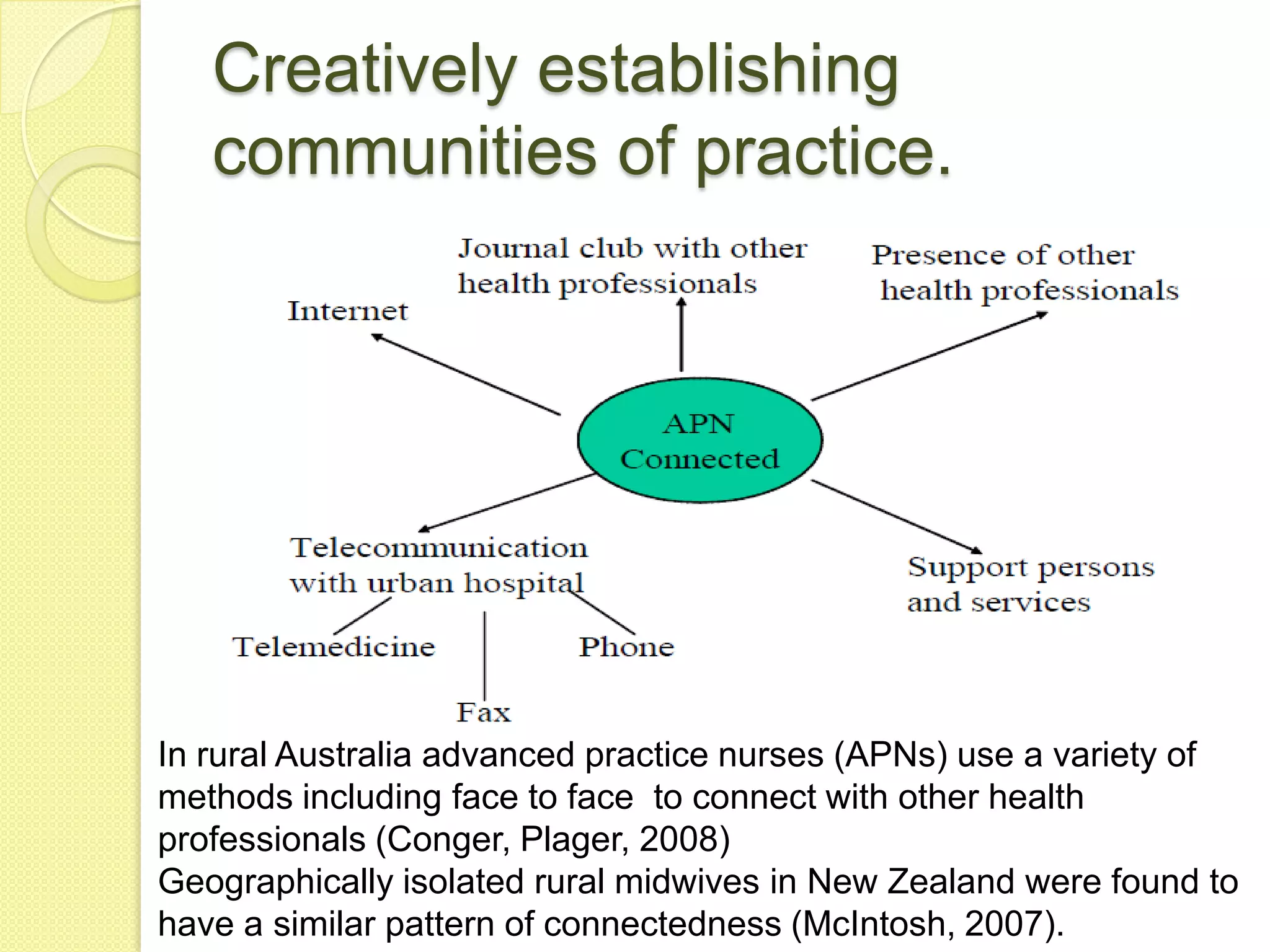

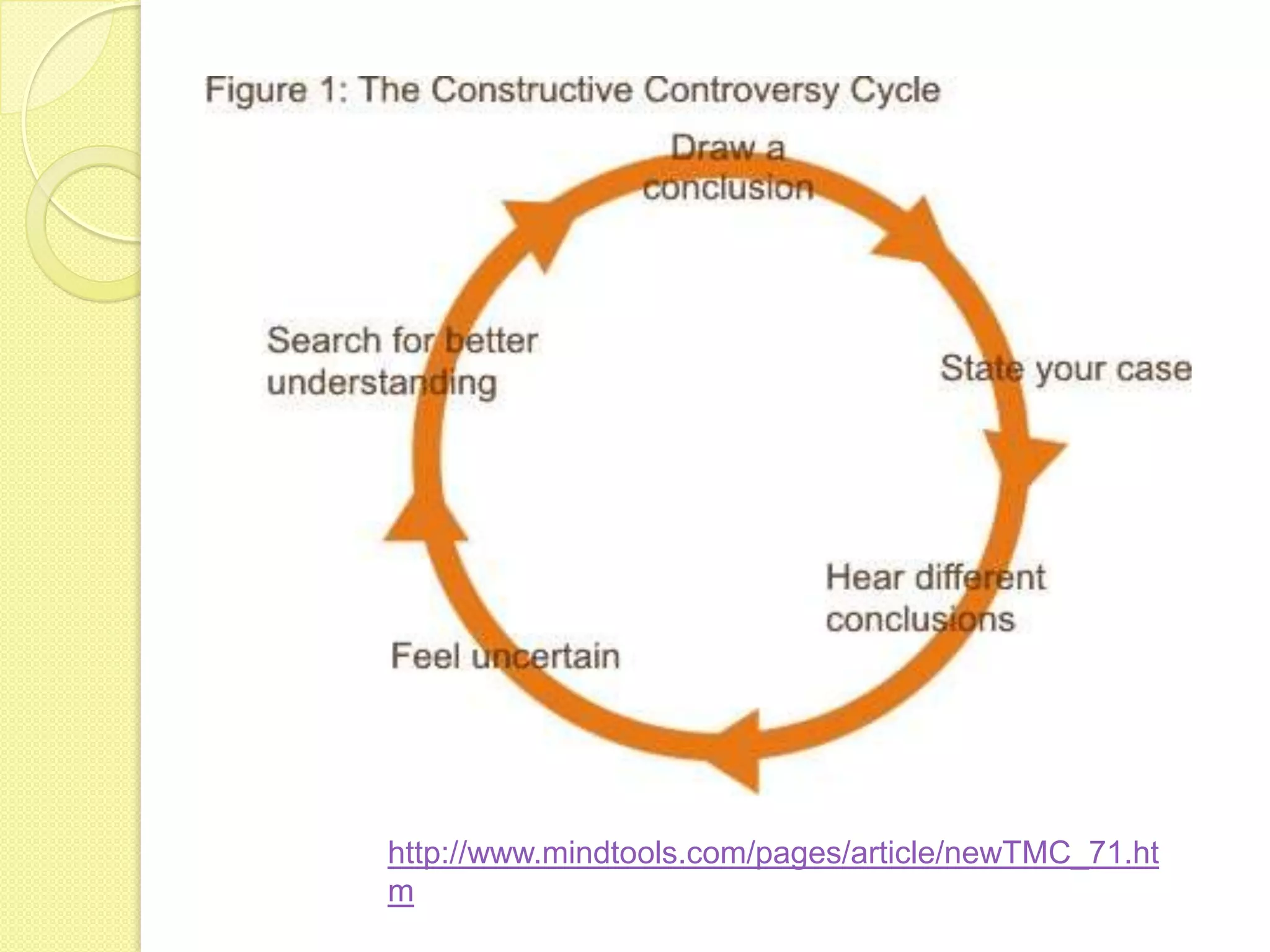

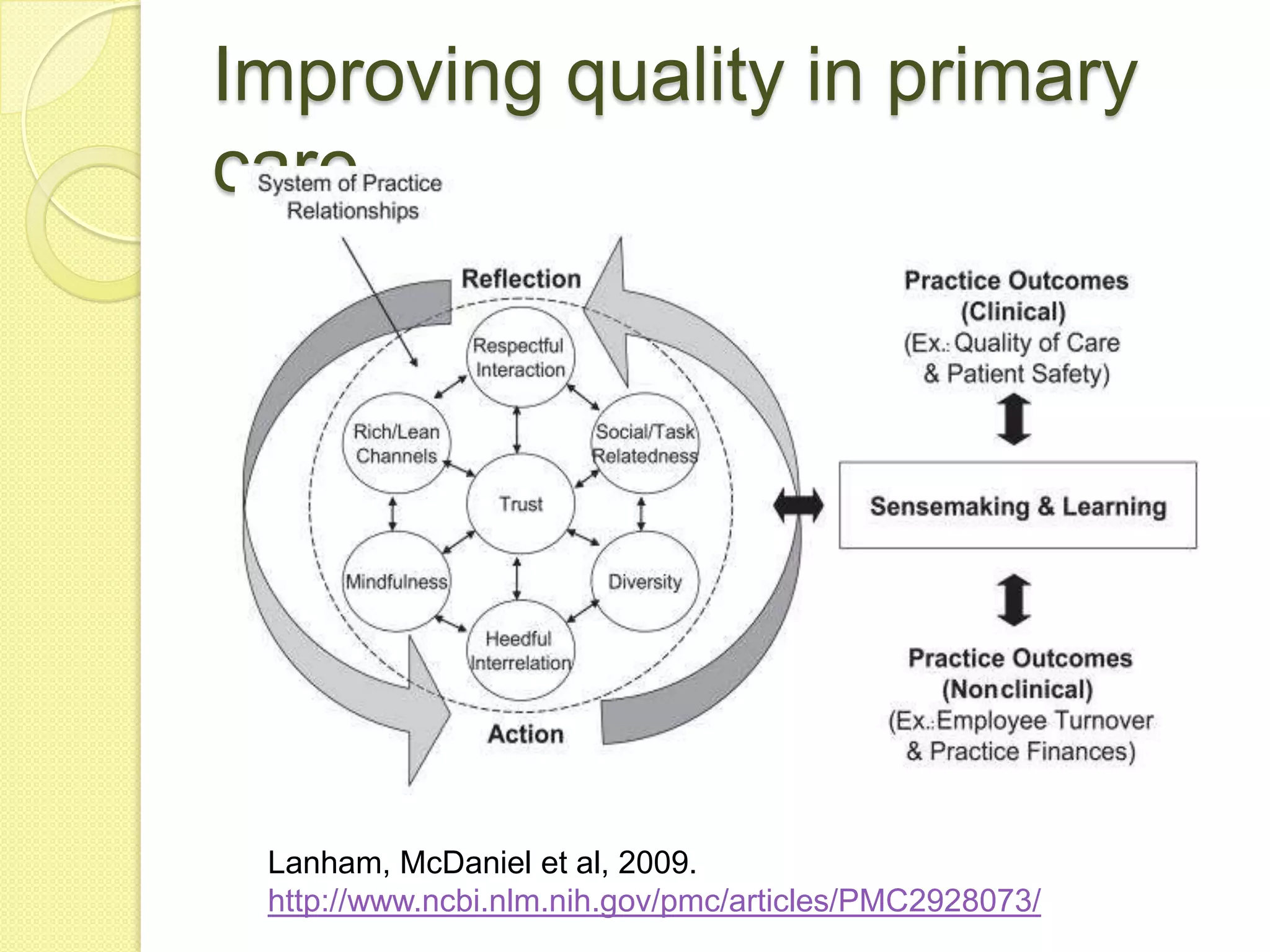

This document summarizes a presentation on collaboration and communities of practice among rural midwives in New Zealand. It discusses how midwives engage in various communities of practice centered around caring for mothers and infants. These communities can include other midwives, doctors, nurses and lay groups. While communities of practice facilitate knowledge sharing, relationships between groups can also lead to tensions or controversy which need to be resolved constructively to advance learning and improve quality of care. Effective collaboration between interconnected but diverse communities of practice is important for supporting rural midwifery practice.