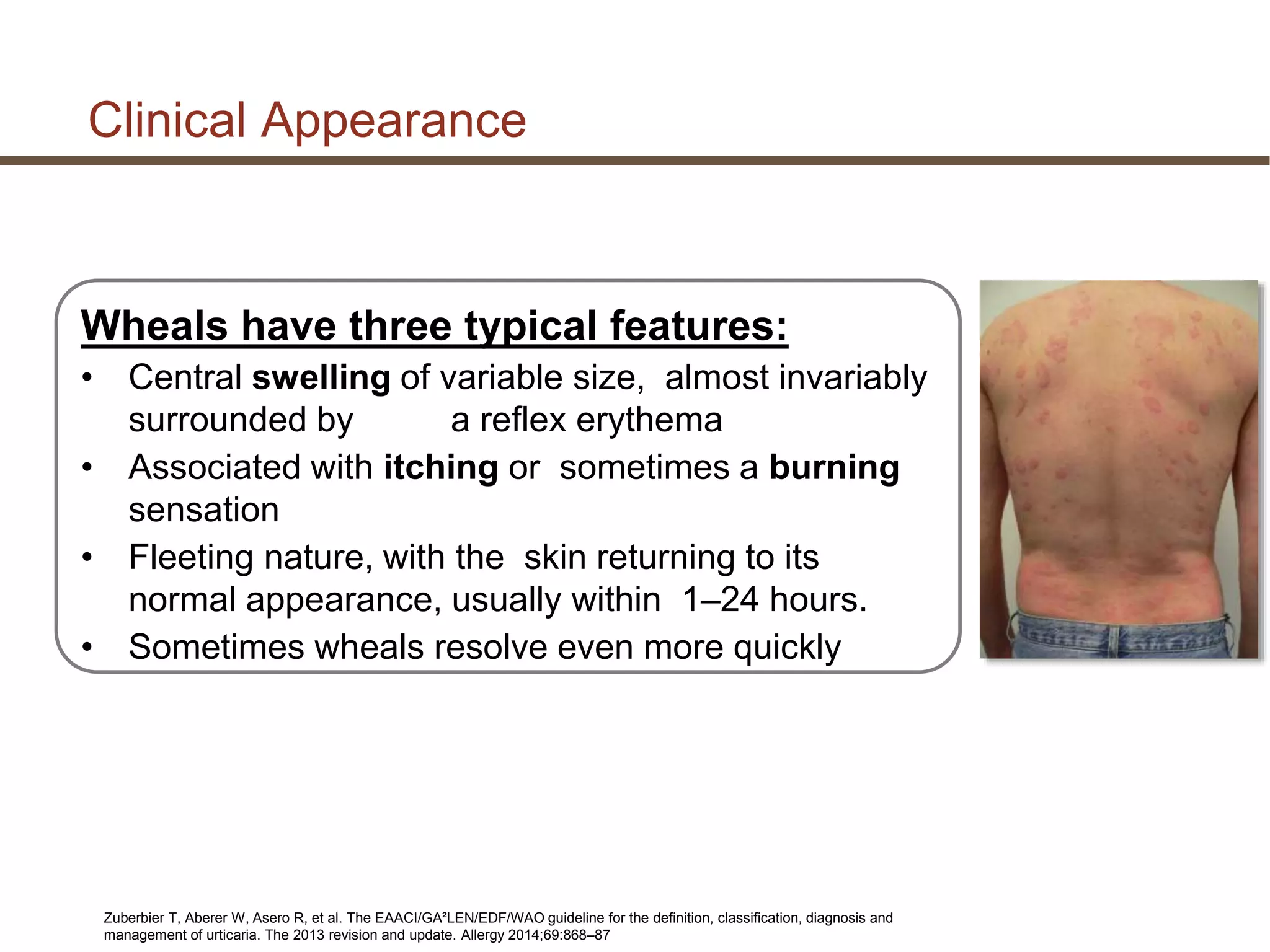

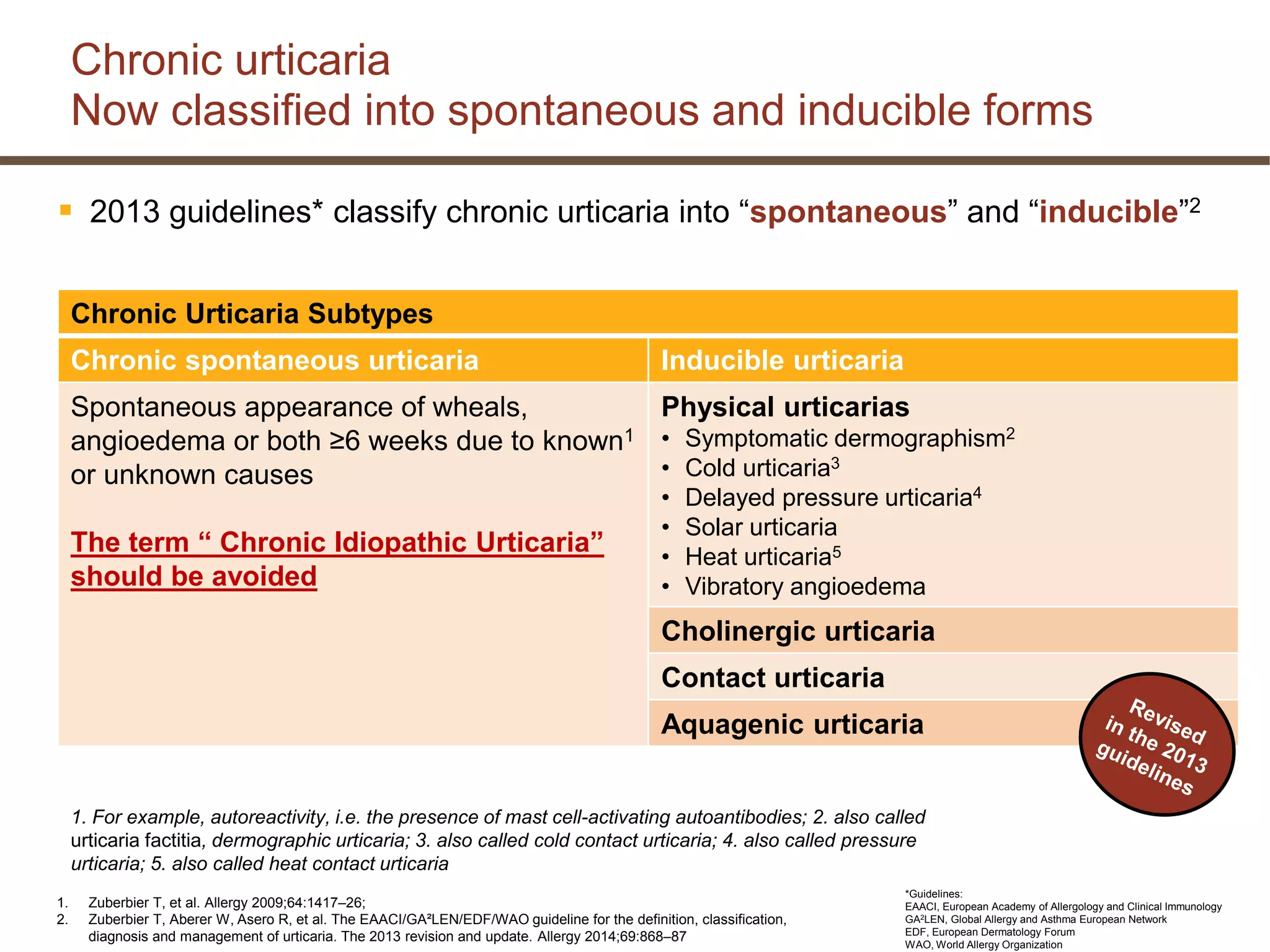

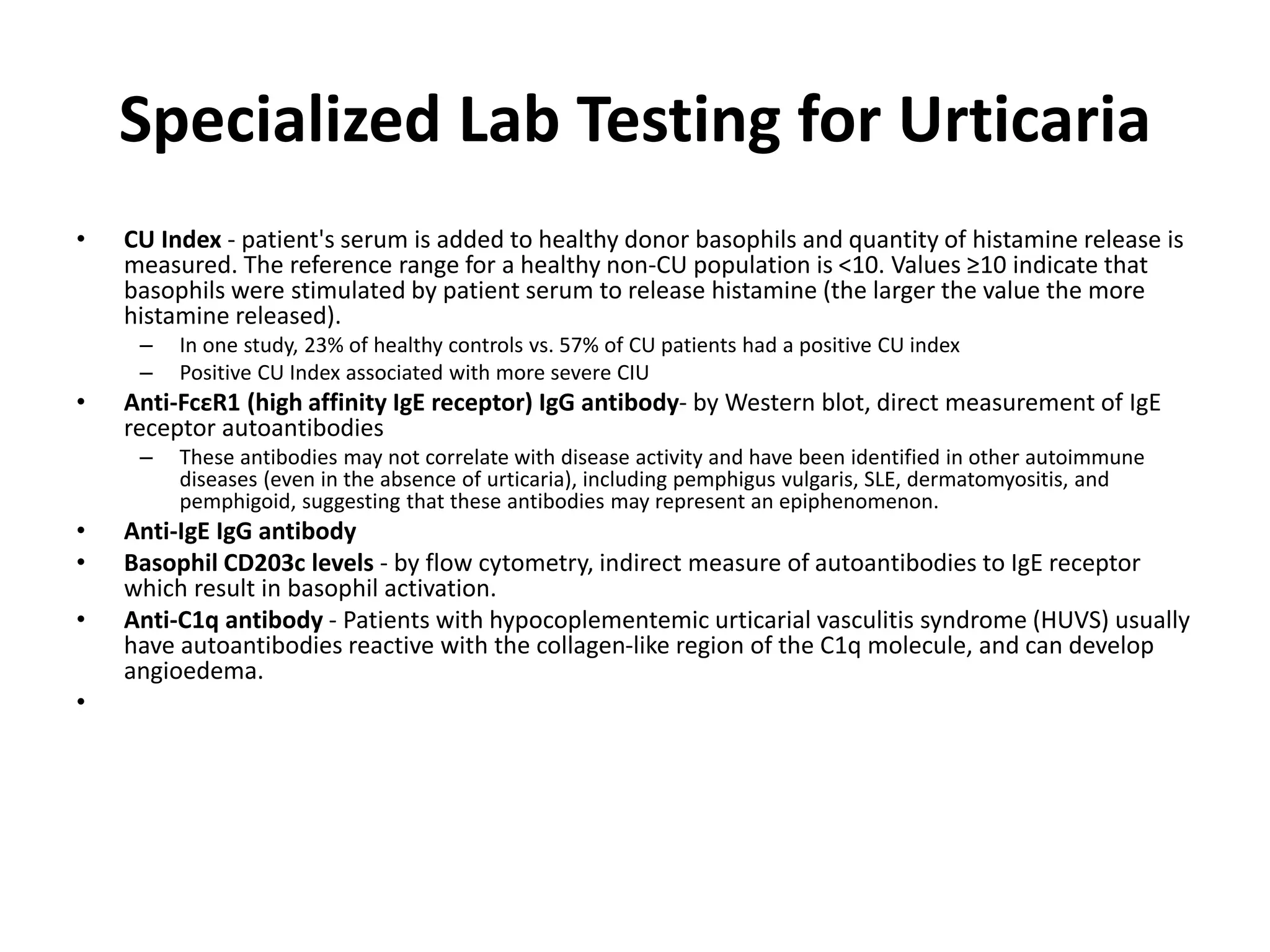

This document discusses updates in the management of chronic urticaria. It begins with definitions of acute and chronic urticaria, noting that chronic urticaria is defined as symptoms lasting more than 6 weeks. It then discusses the classification of urticaria as either spontaneous or inducible. Mast cell activation and degranulation are identified as the key pathological mechanisms involved in urticaria symptoms. Autoimmune processes involving immunoglobulins such as IgG and IgE autoantibodies are also discussed as potential pathological factors in chronic urticaria. Guidelines for the treatment of urticaria have been updated.

![ LTRAs are associated with a low level of evidence for efficacy in

urticaria

• The best evidence is for montelukast

In urticaria, topical corticosteroids are not helpful (with the possible

exception of pressure urticaria on the soles of the feet [low evidence])

• If systemic corticosteroids are used, doses between 20–50 mg/day are

required

• Adverse effects occur during on long-term use

• There is a strong recommendation against long-term use of

corticosteroids outside specialist clinics

• In many countries, corticosteroids are not licenced for use in urticaria

Description of LTRAs has been changed since 2009 and now notes that the best evidence is for montelukast.

LTRA = leukotriene receptor antagonist.

Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and

management of urticaria. The 2013 revision and update. Allergy 2014;69:868–87

Treatment of antihistamine-refractory patients:

LTRAs and corticosteroids](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/okbachronicurticaria-150504070103-conversion-gate01/75/chronic-urticaria-68-2048.jpg)