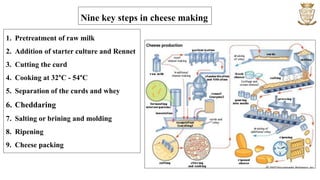

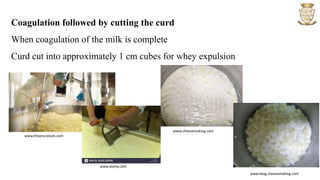

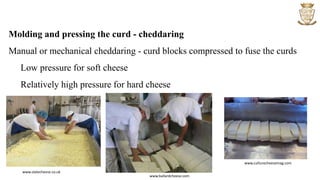

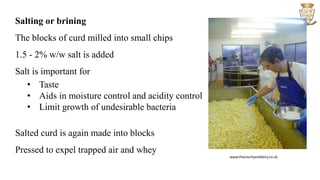

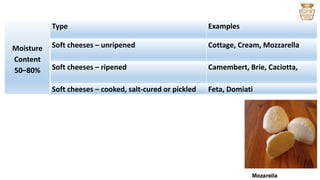

Cheese is produced through coagulation of milk proteins and entrapment of milk fat. The key steps in cheese making are pretreatment of milk, addition of starter cultures and rennet, cutting the curd, cooking, separating curds and whey, pressing, salting, ripening, and packing. There are over a thousand types of cheeses which vary based on properties and treatment of milk, moisture content, and role of microorganisms in ripening. Common types include soft cheeses like mozzarella, semi-soft cheeses like gouda, hard cheeses like cheddar, and very hard cheeses like parmesan.