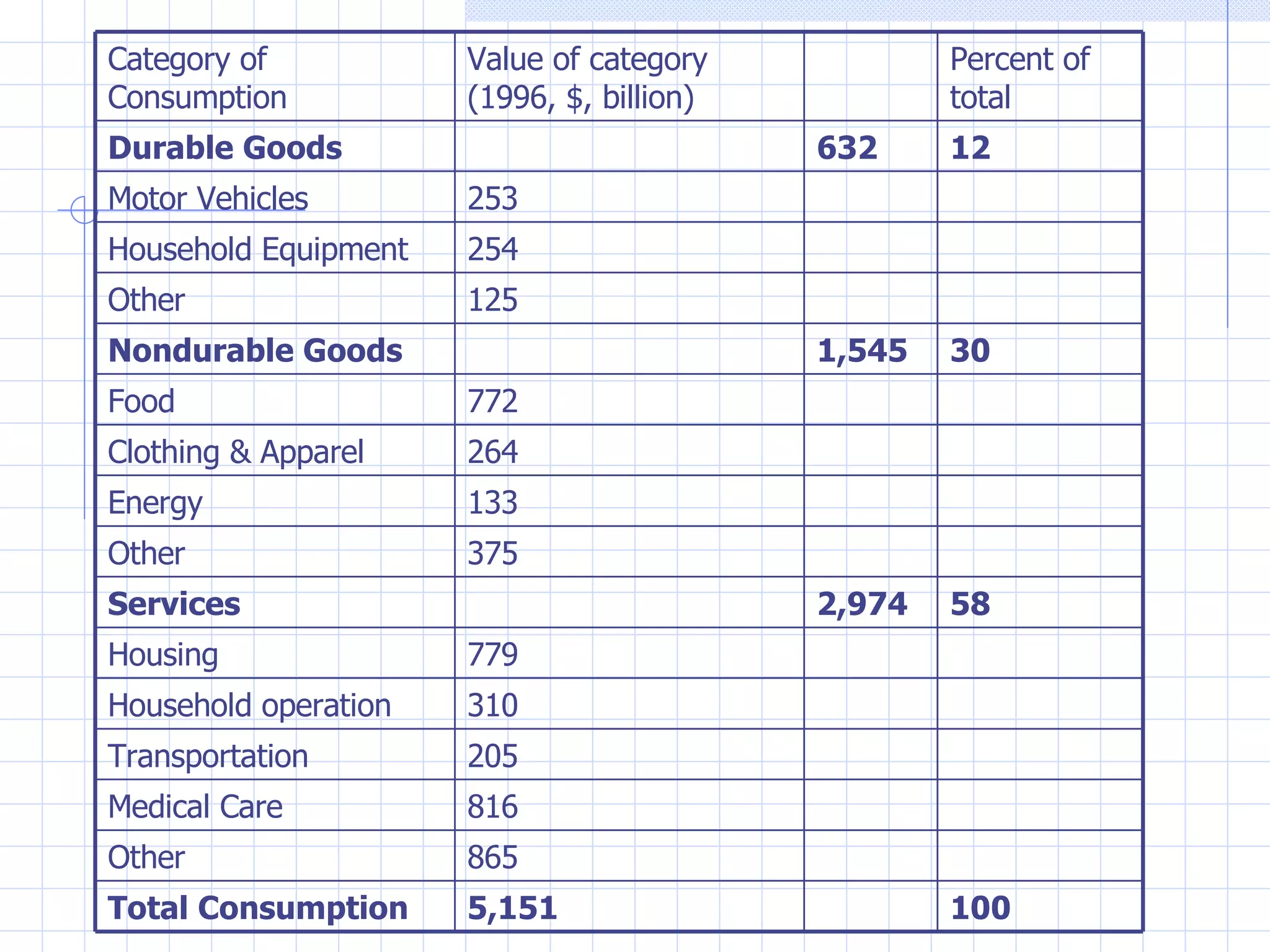

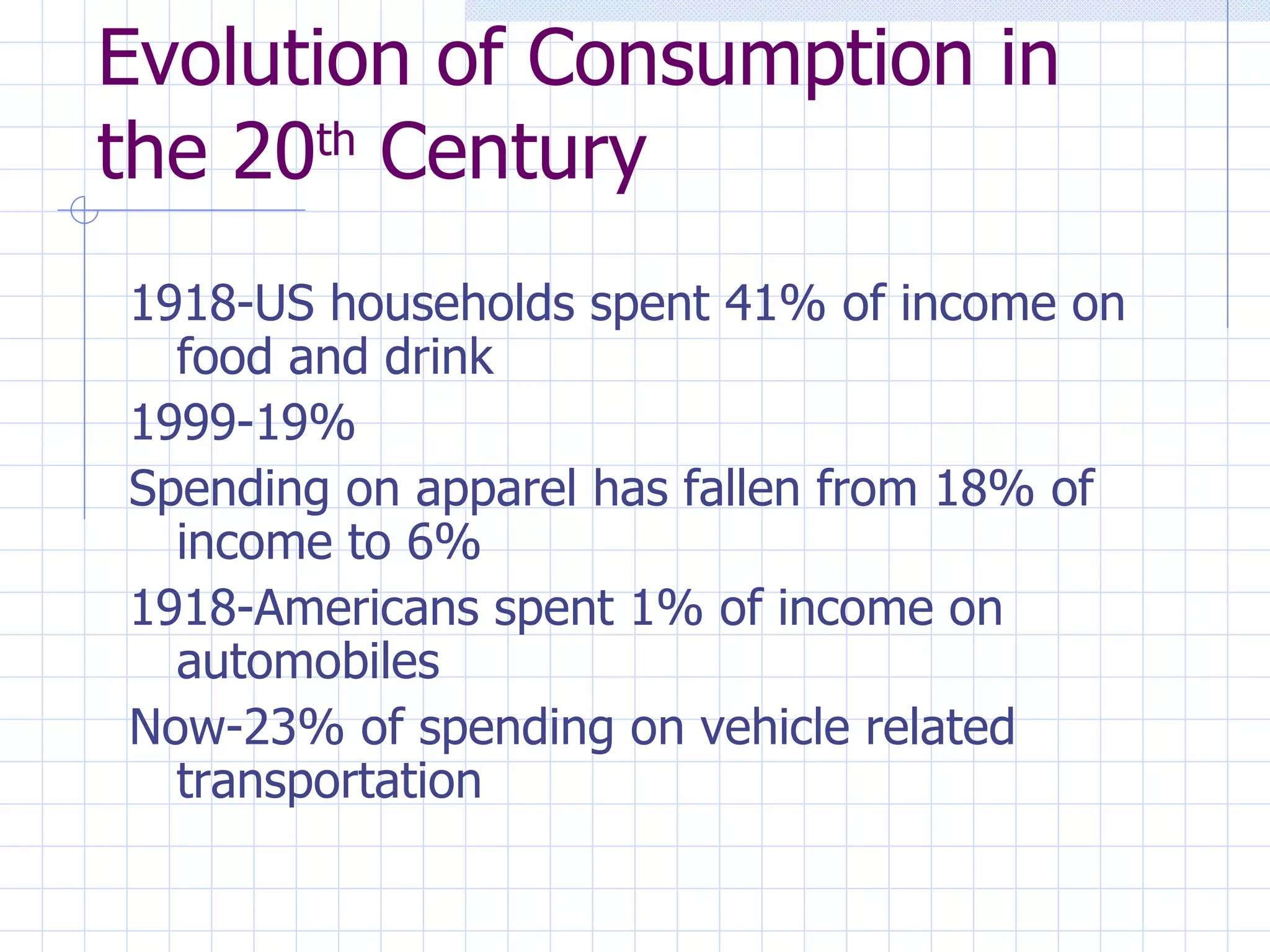

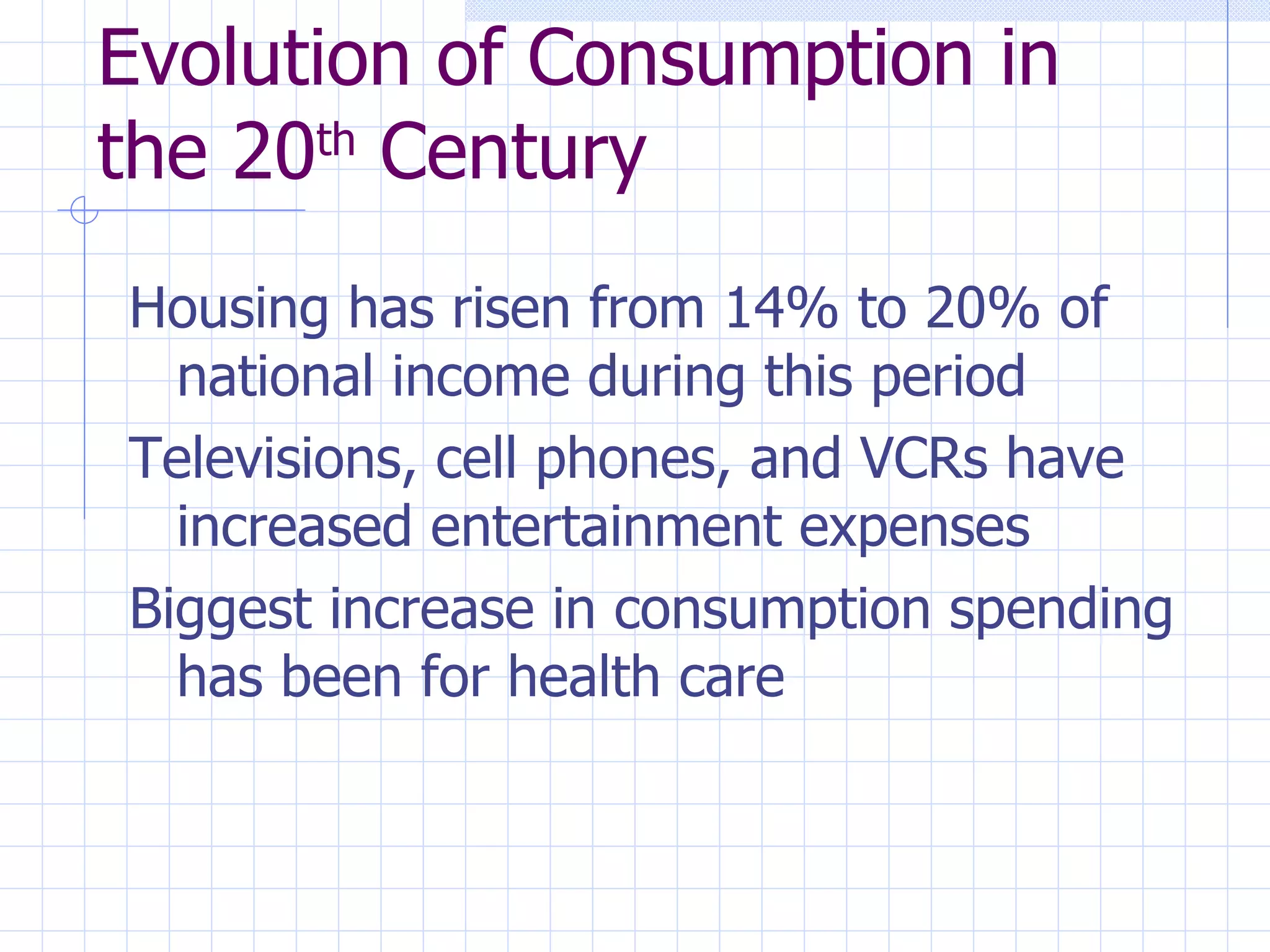

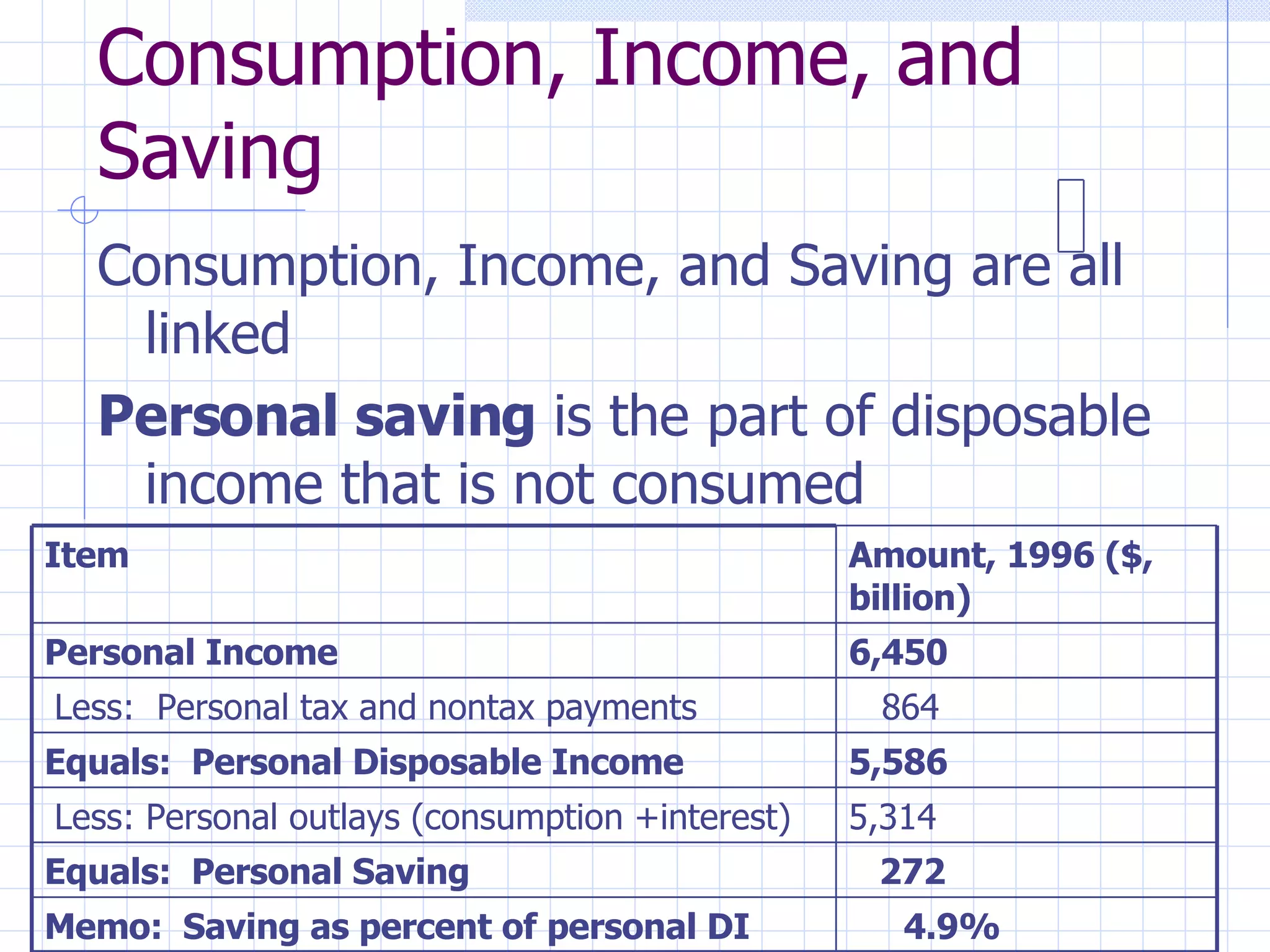

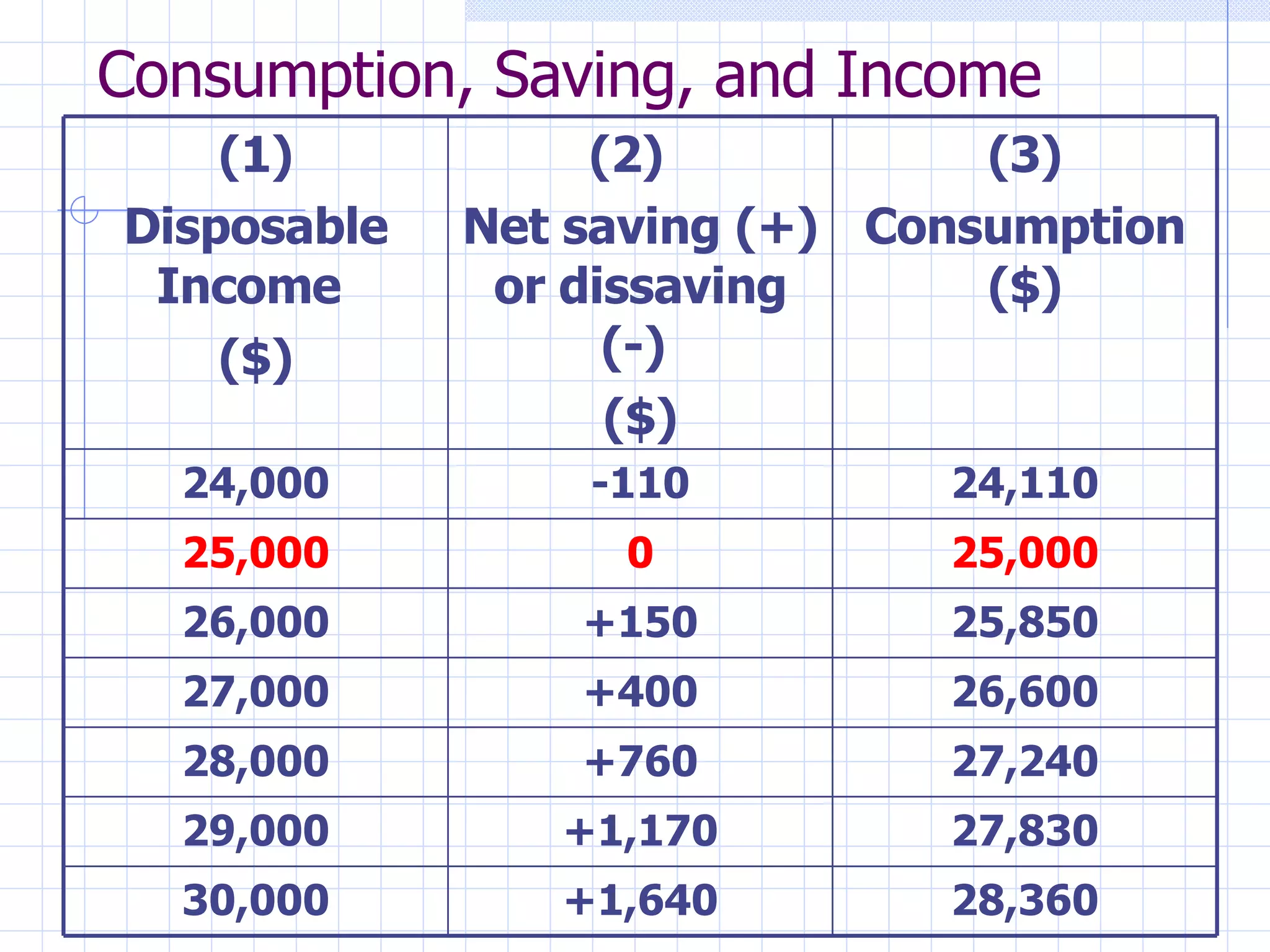

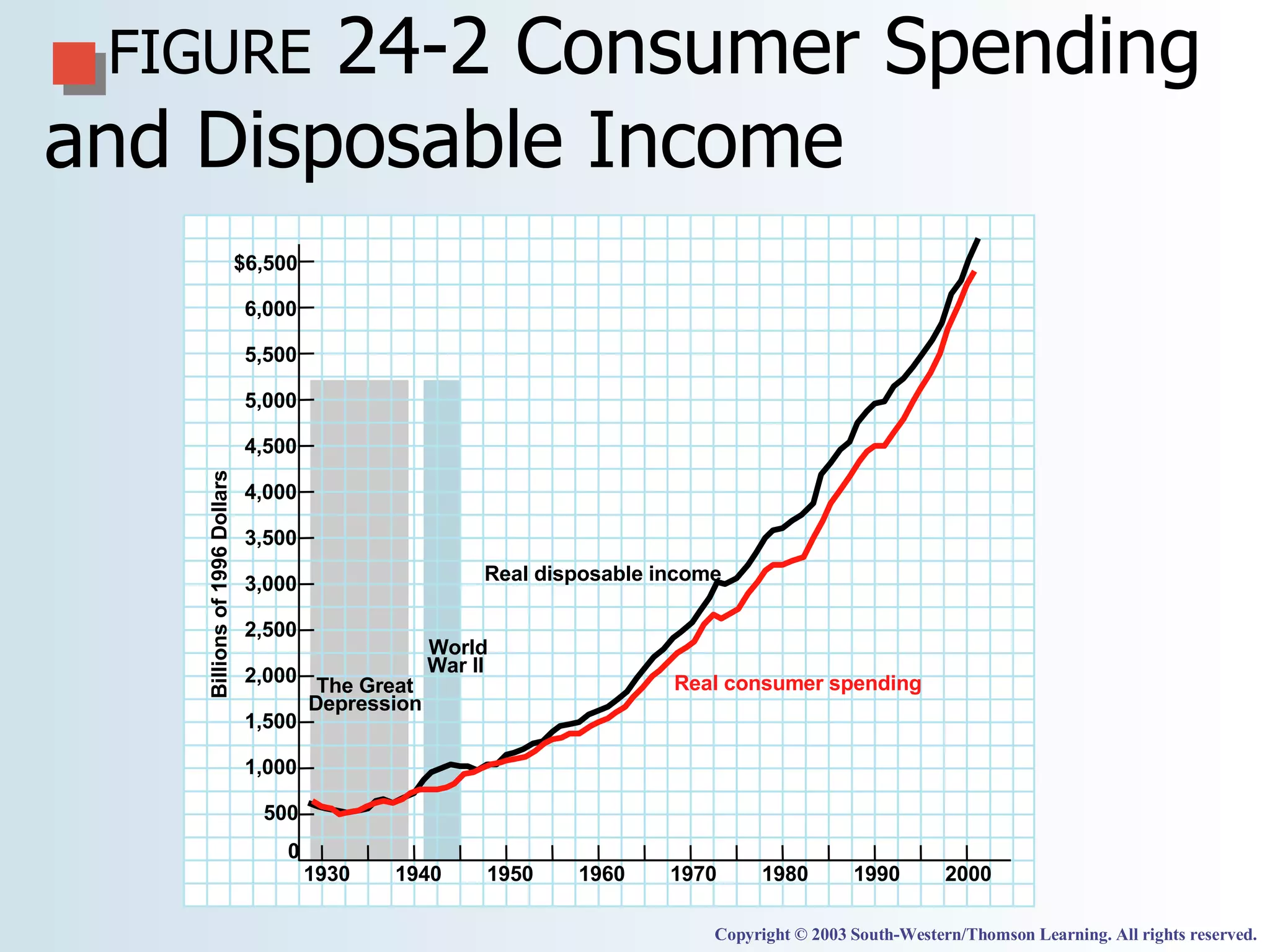

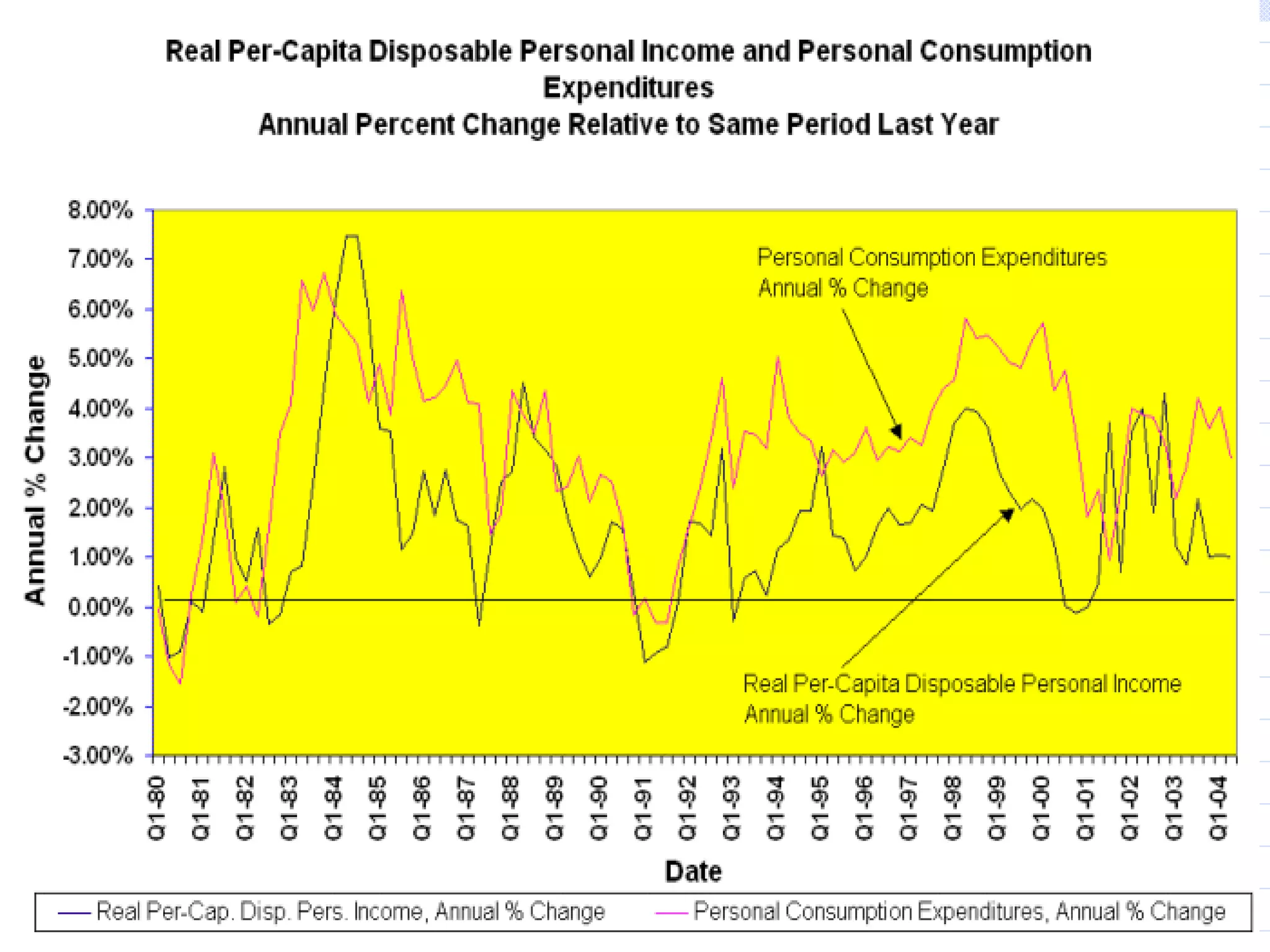

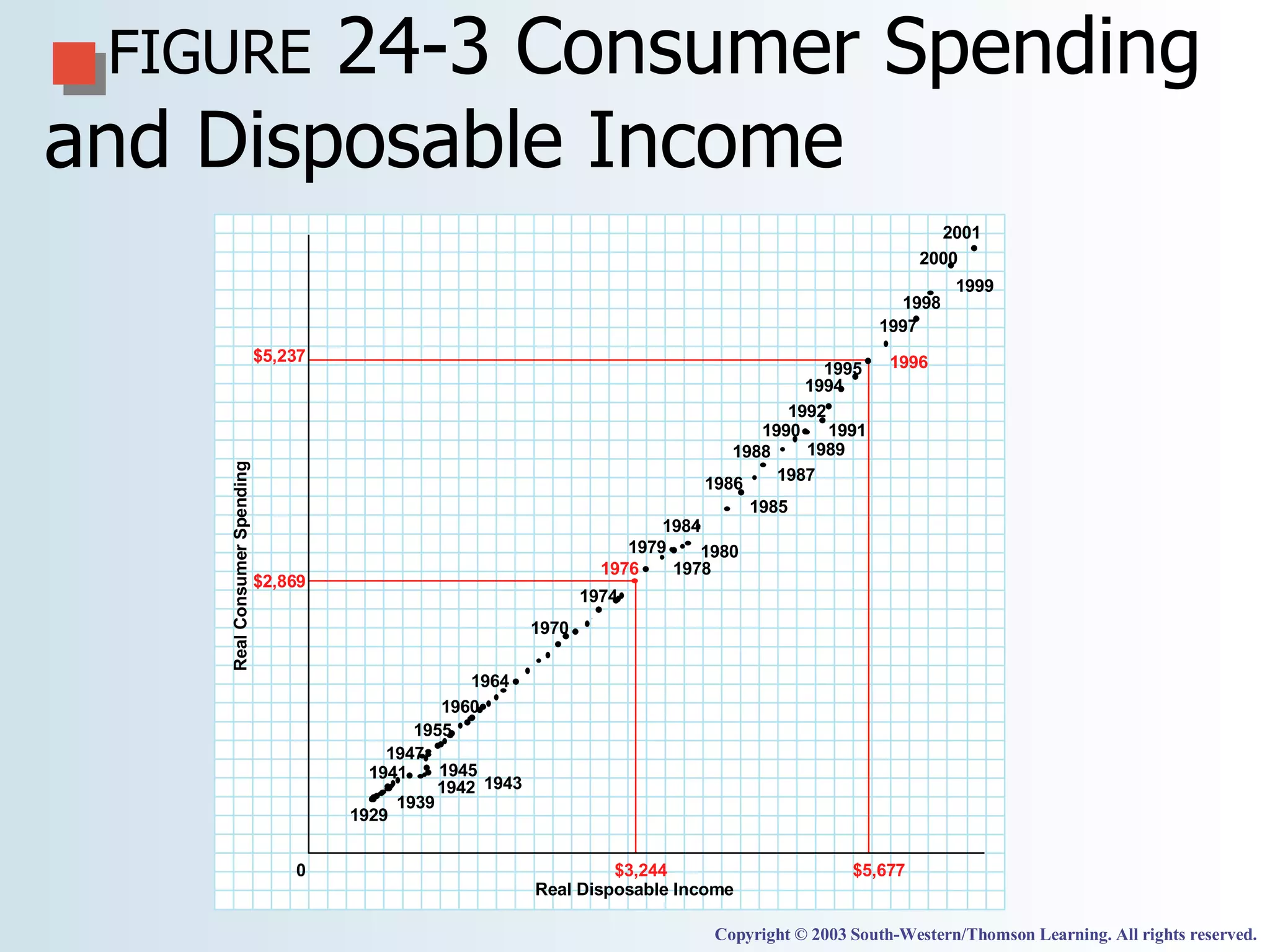

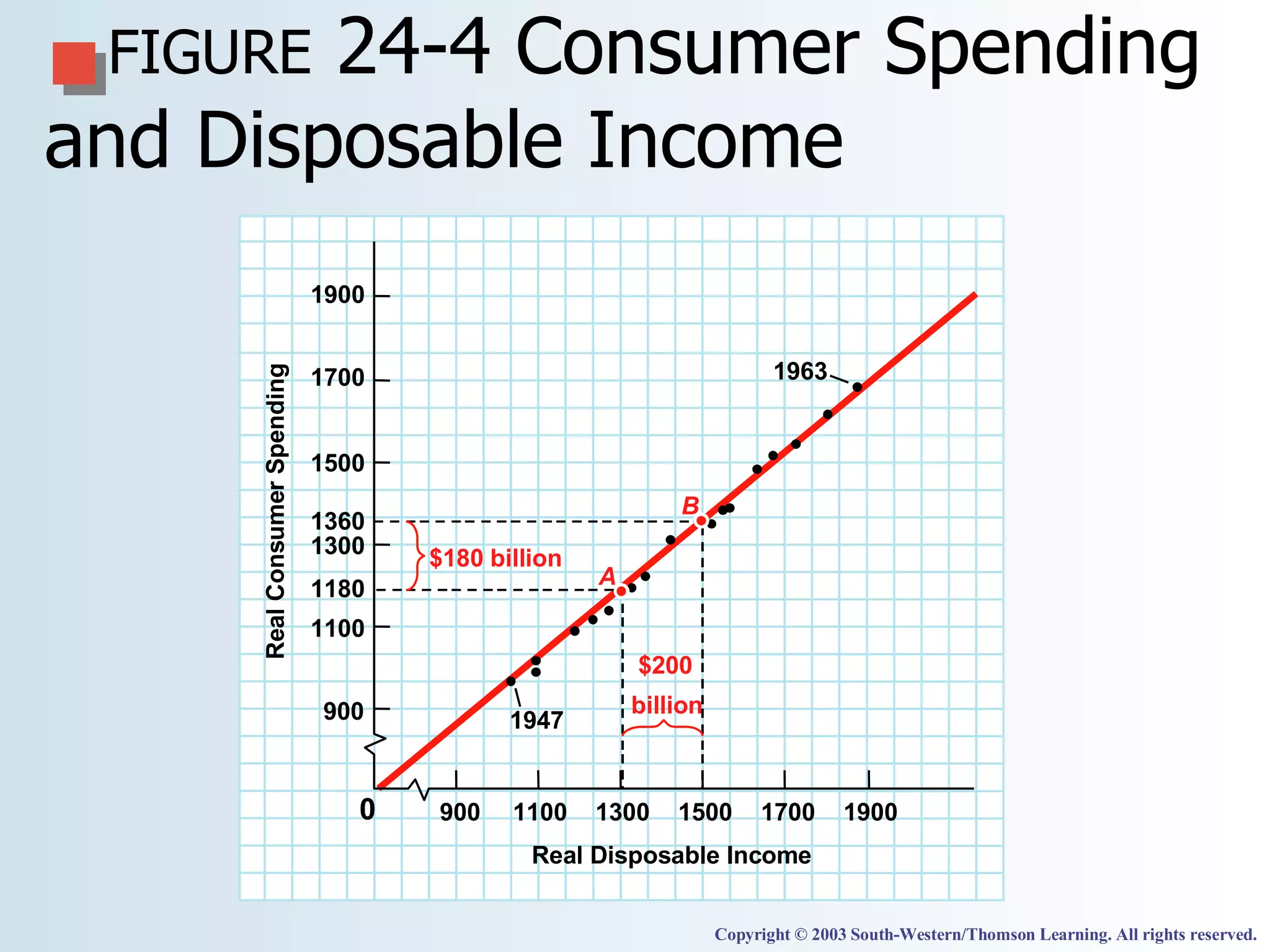

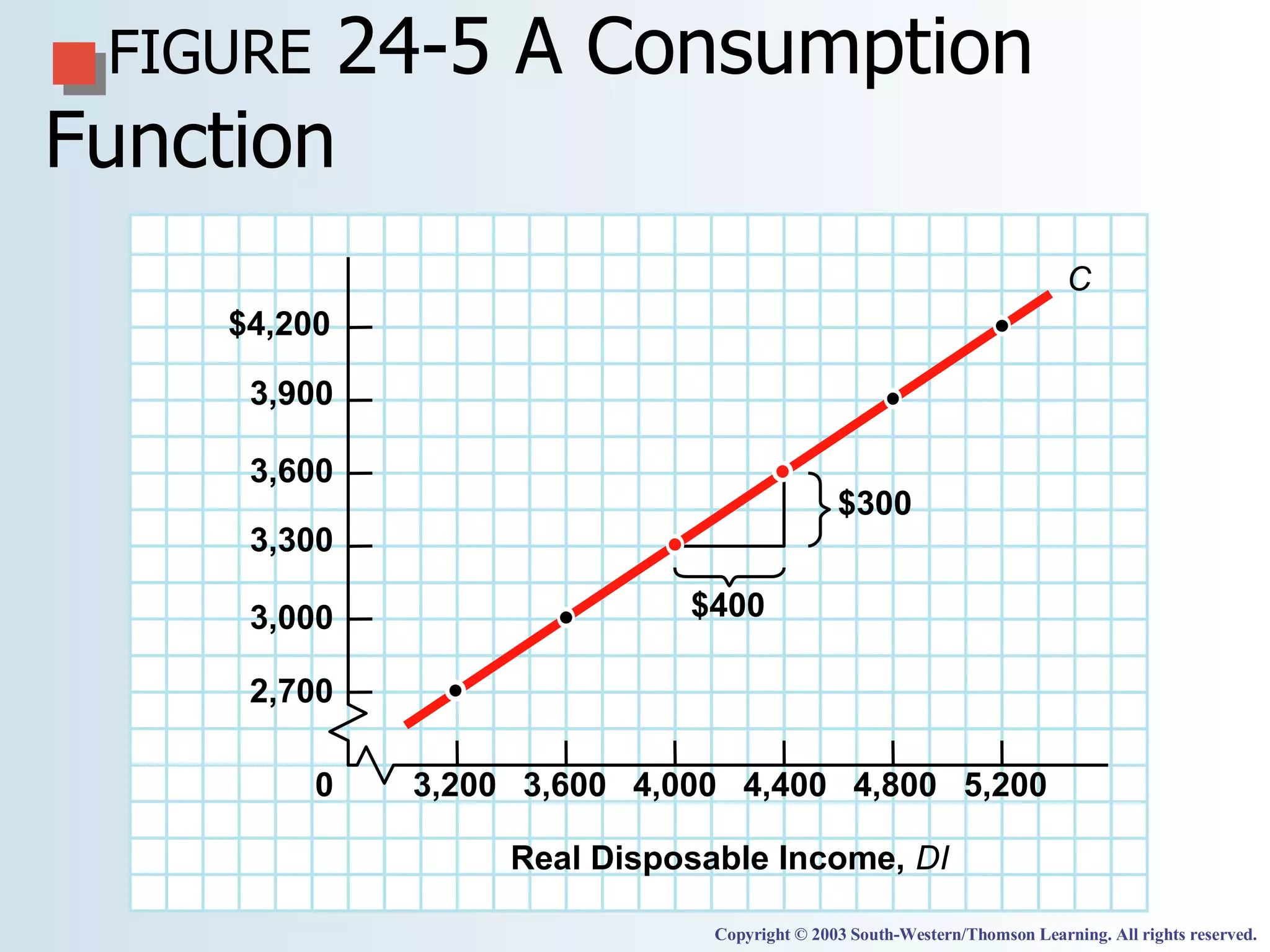

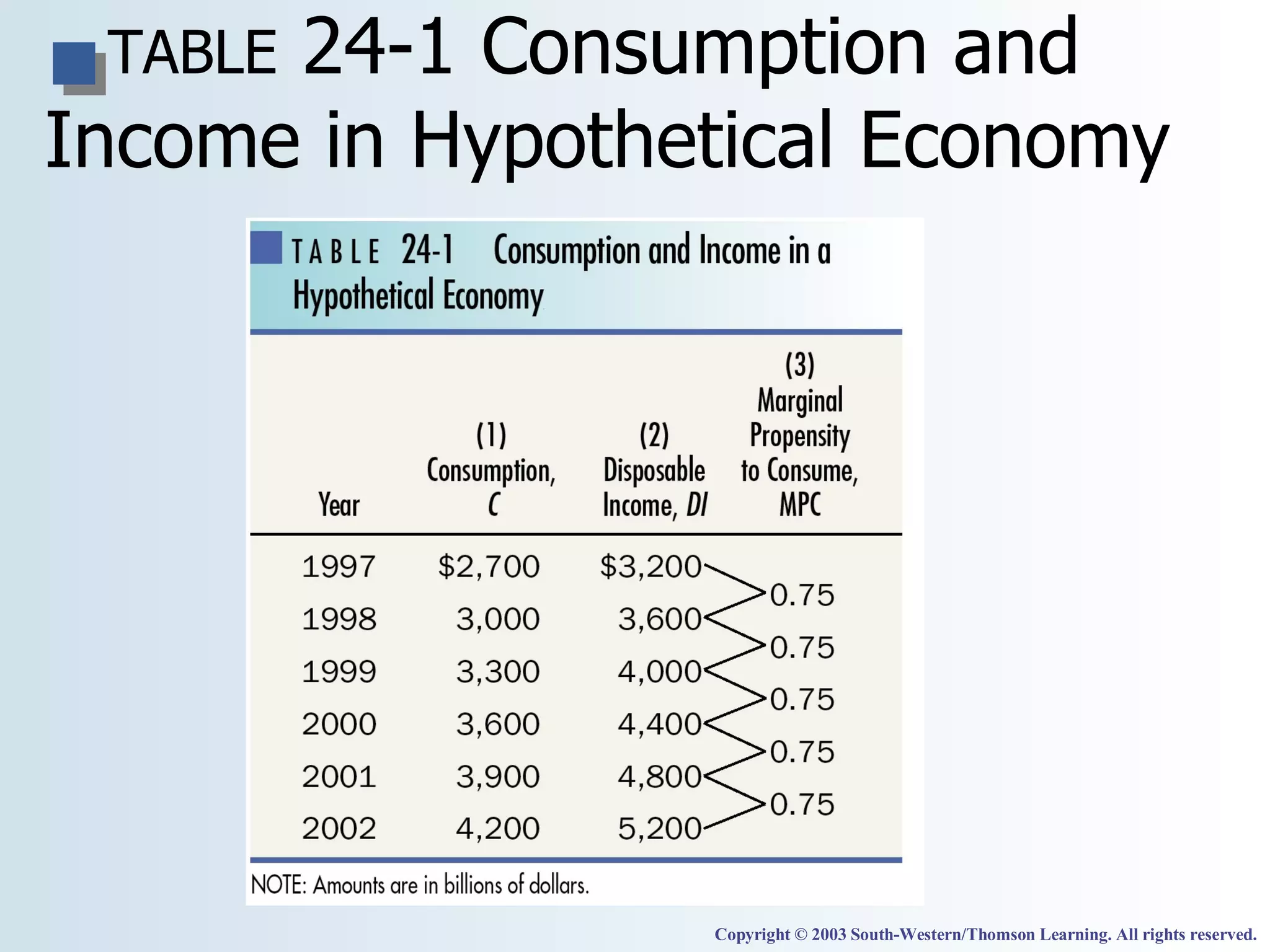

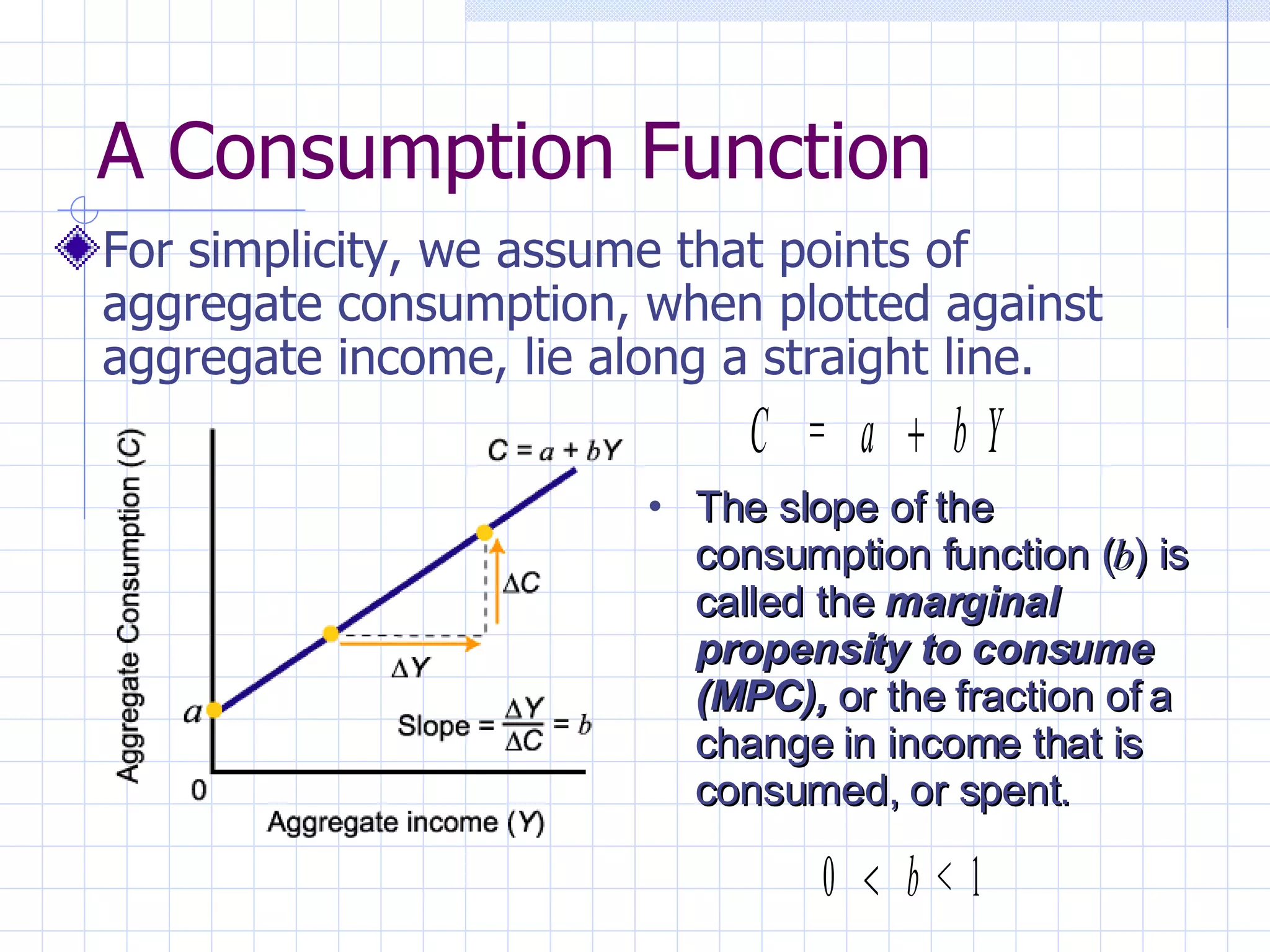

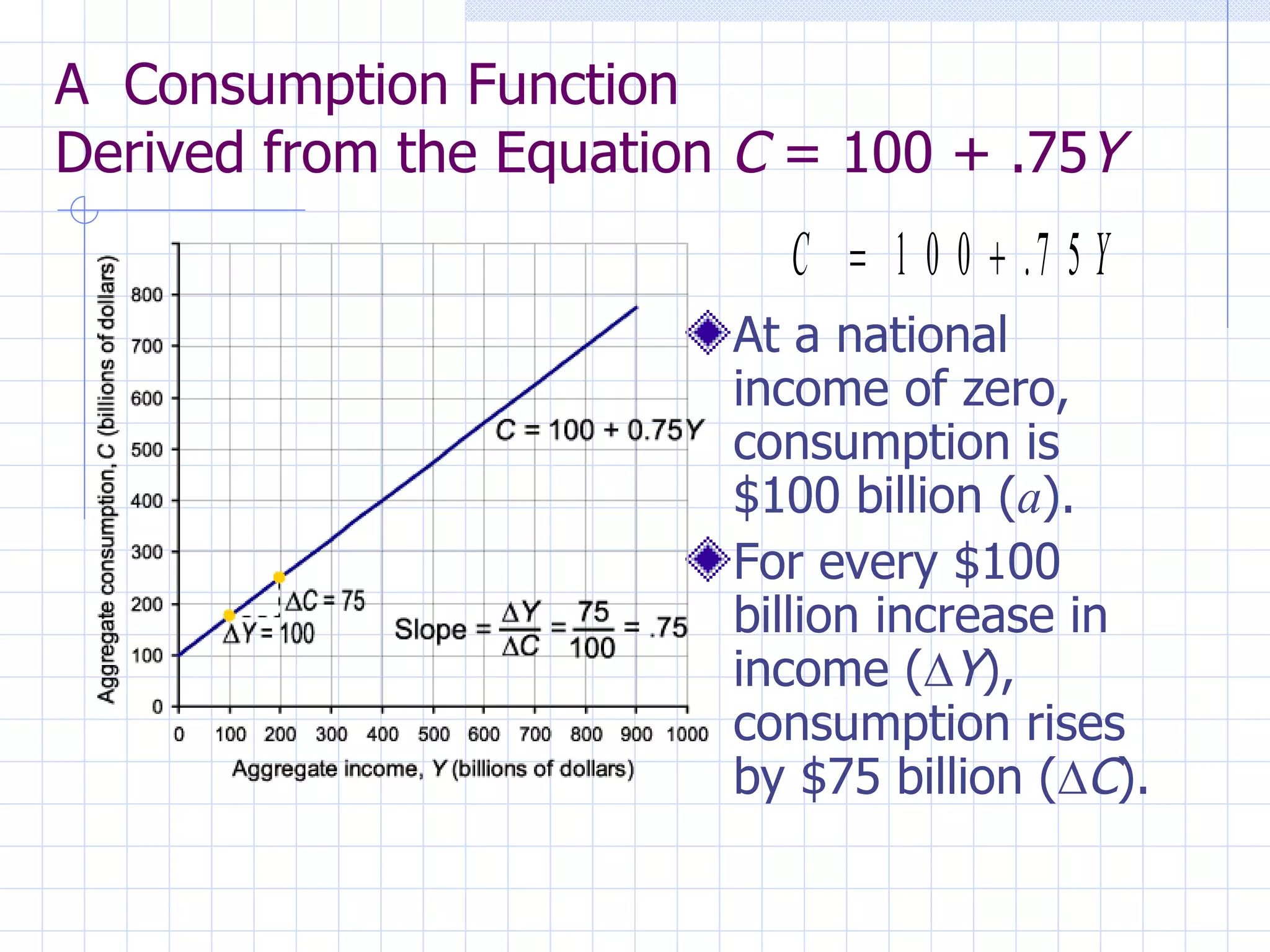

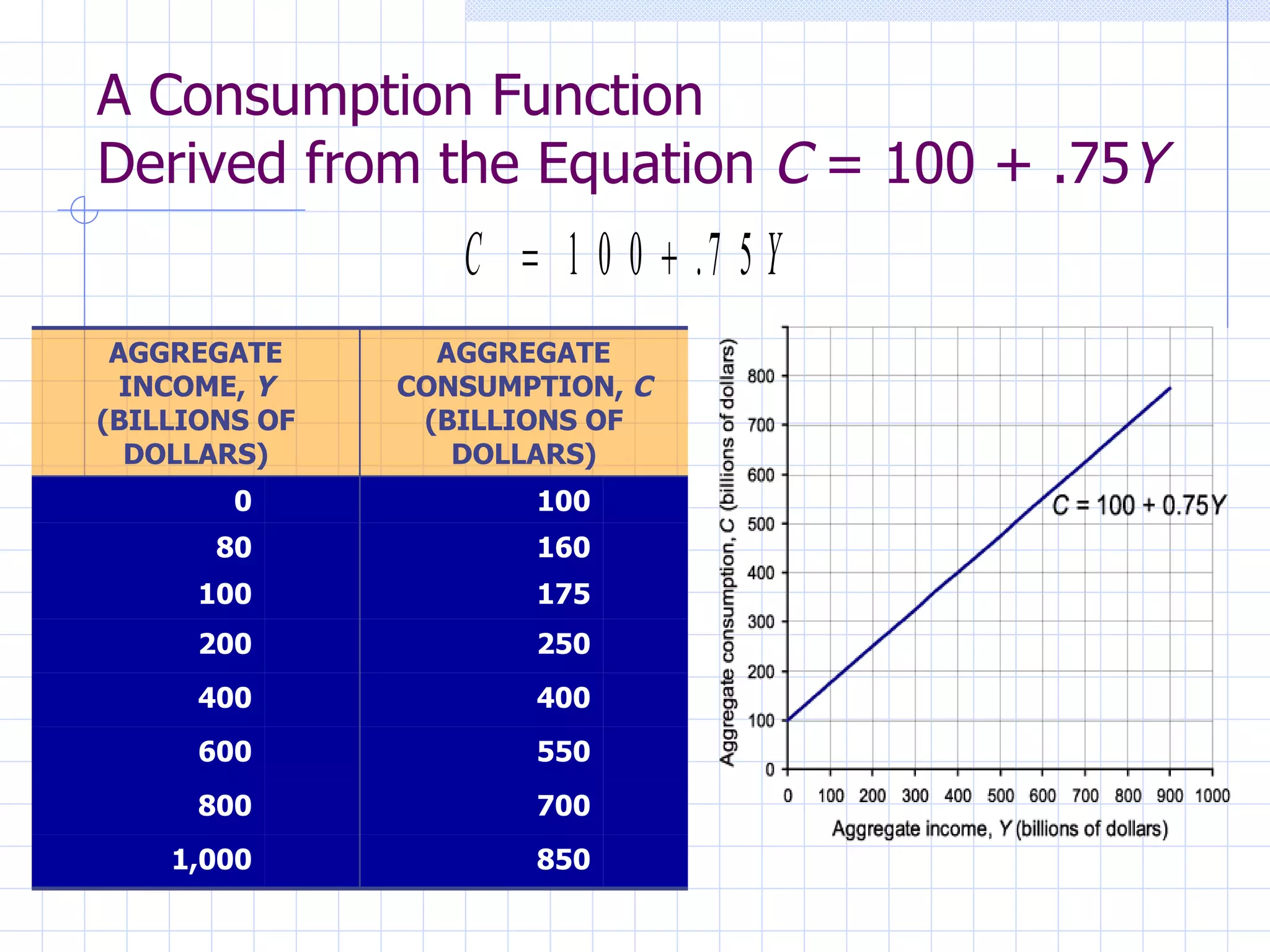

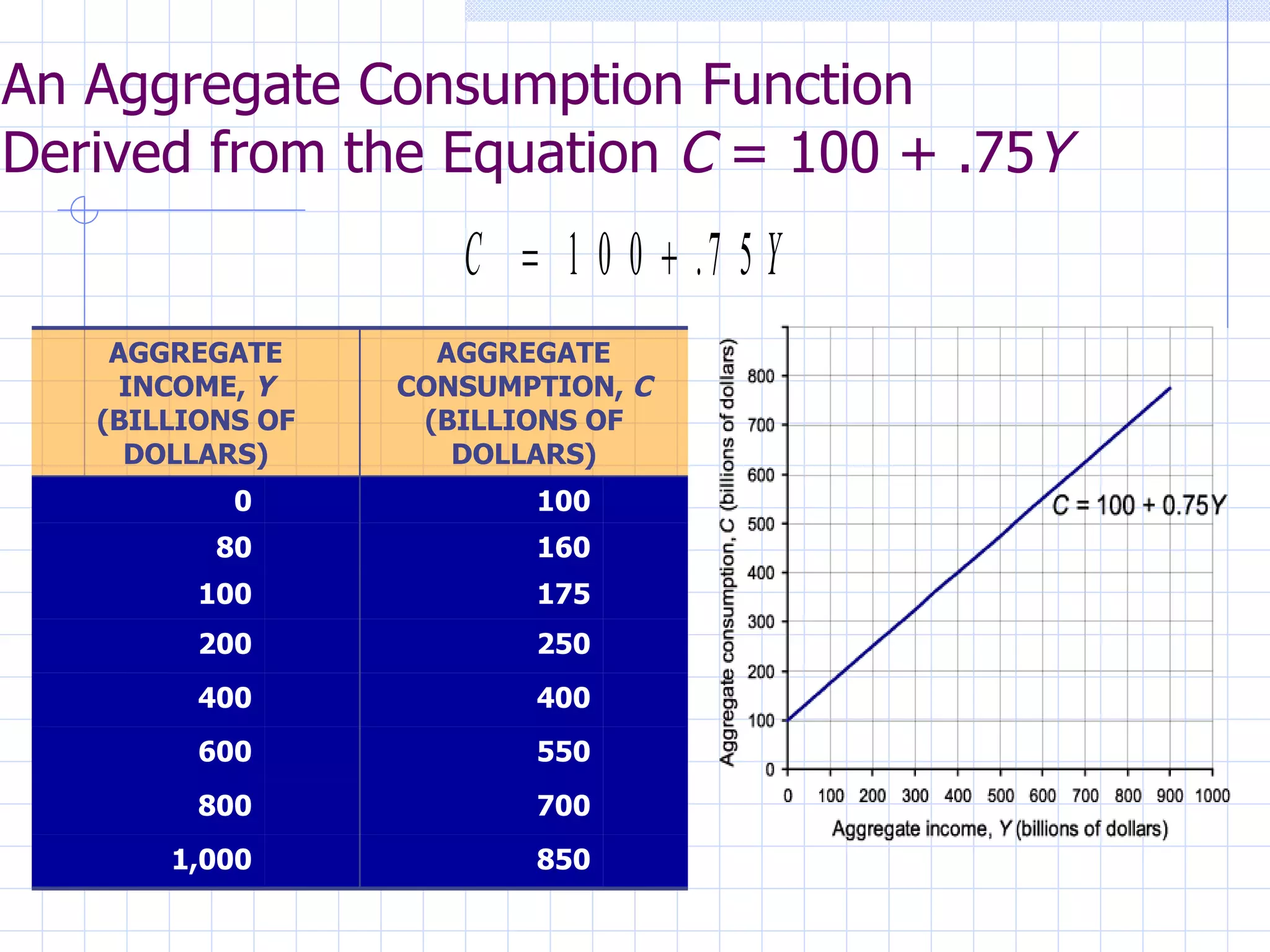

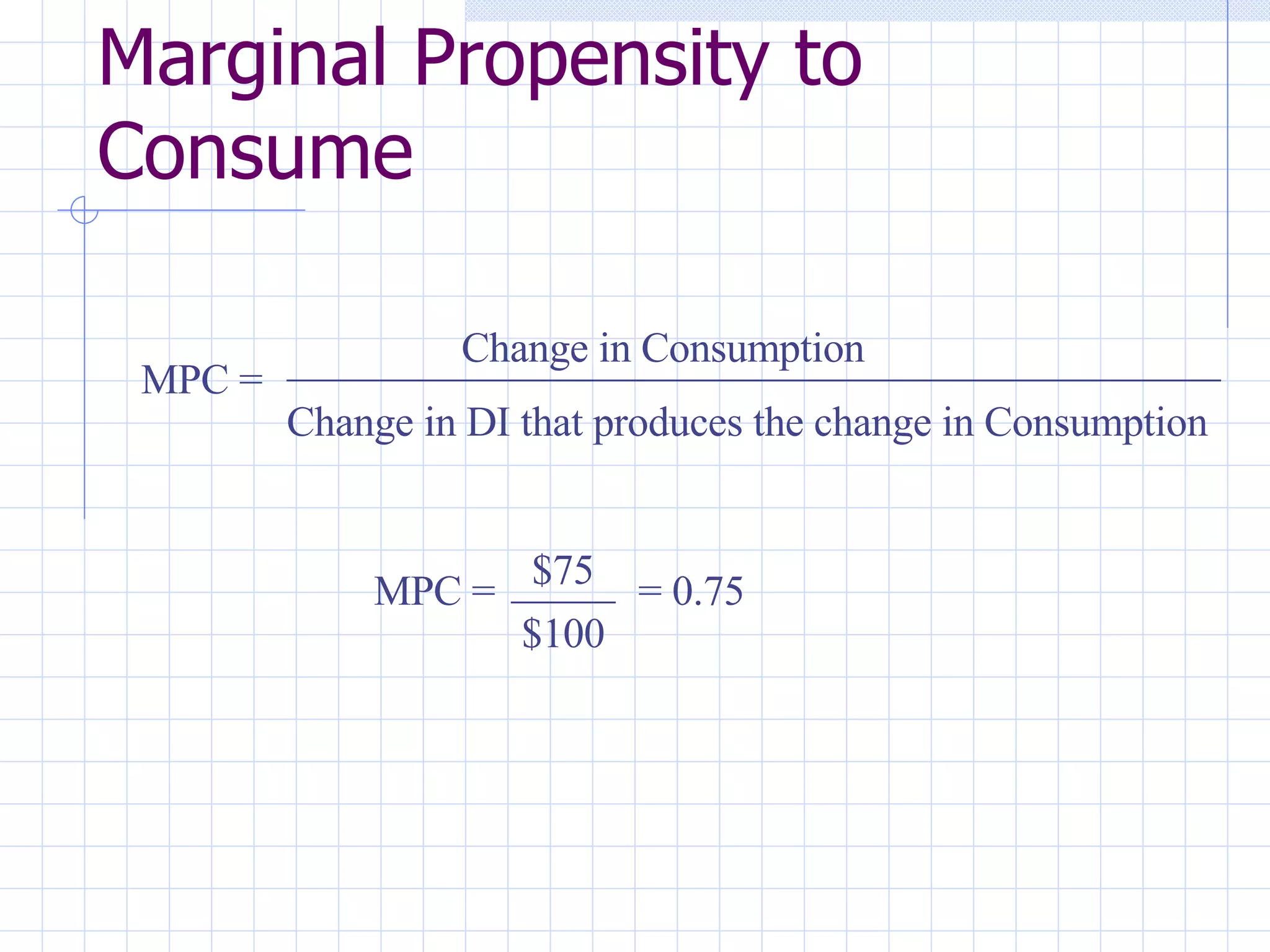

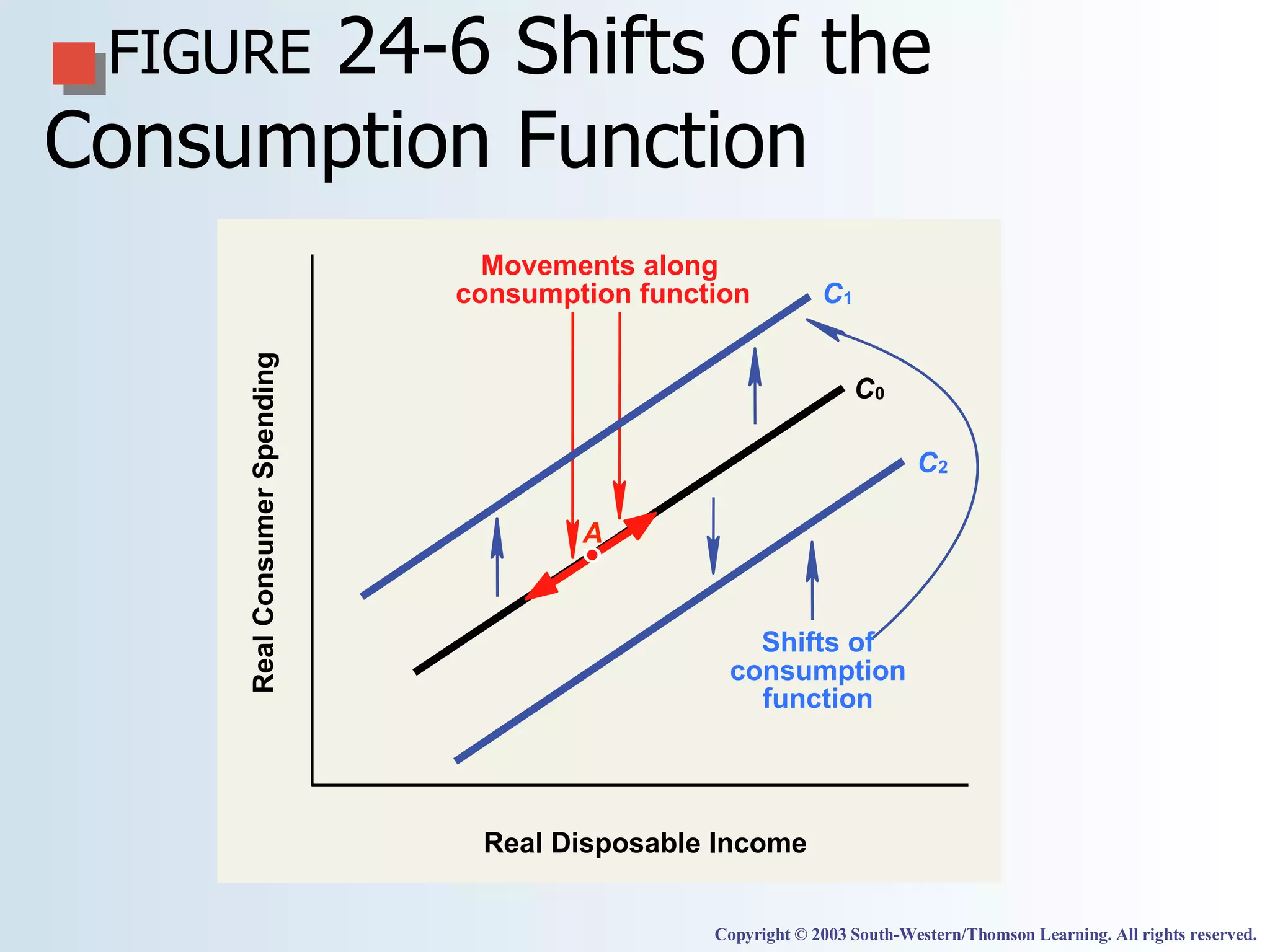

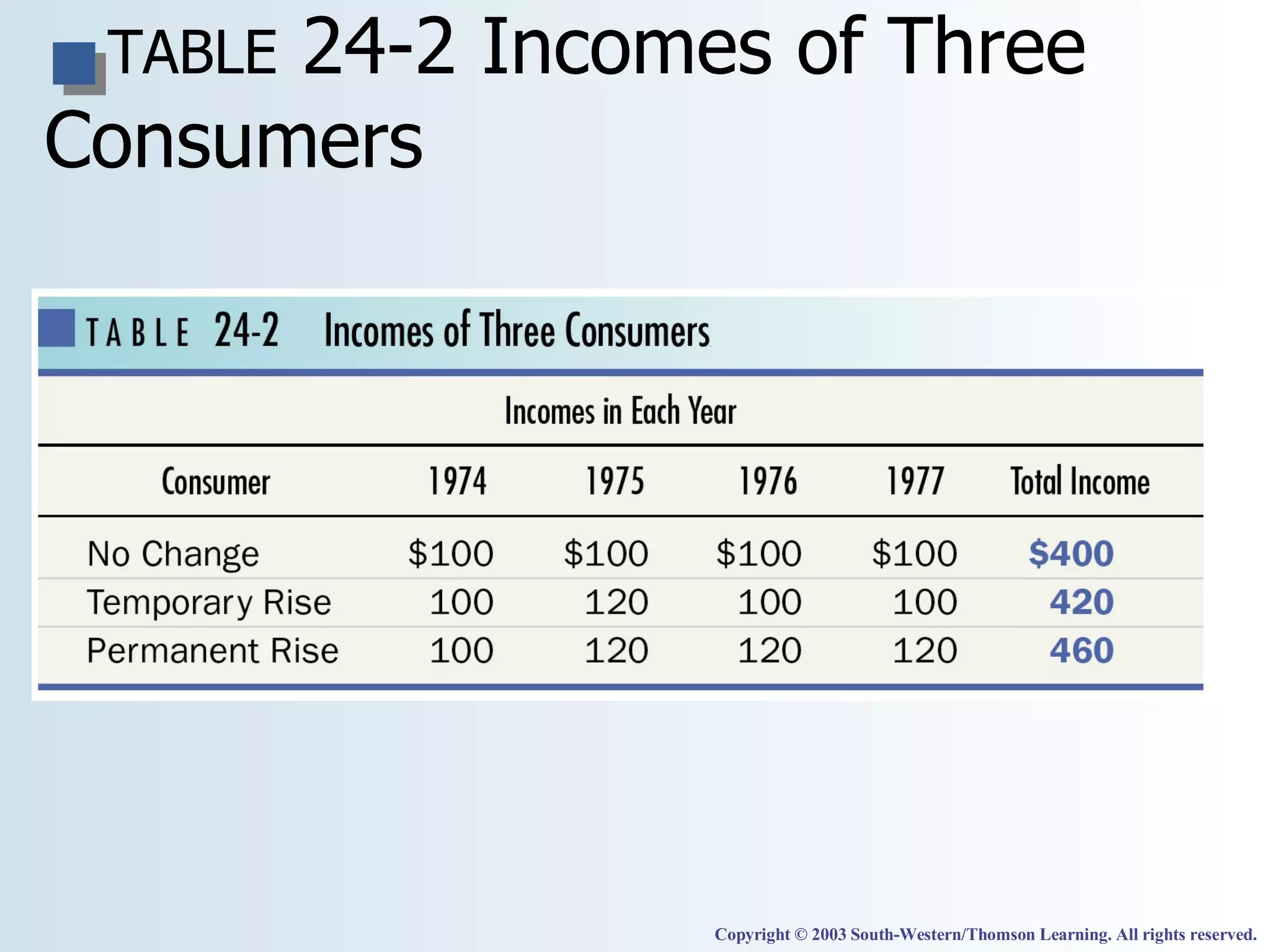

The document discusses aggregate demand and factors that influence consumption. It introduces the consumption function, which shows the relationship between consumption and disposable income. The marginal propensity to consume is the change in consumption from a $1 change in disposable income. Several factors can shift the consumption function, such as wealth, price levels, and expectations about future income. Tax rebates in 1975 and 2001 failed to significantly boost consumption as intended because consumers viewed the increases in income as temporary rather than permanent.