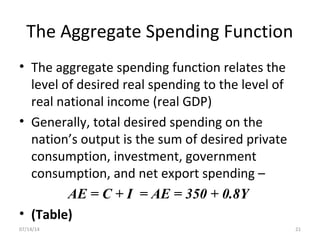

This document provides an overview of macroeconomic theory for determining GDP in the short term. It discusses how GDP is determined by the components of aggregate demand (C, I, G, NX) and how consumption, investment, and aggregate spending functions relate GDP to disposable income. It also covers equilibrium GDP, the multiplier effect of changes in autonomous spending, and how to calculate GDP using a simple consumption function and investment amount.