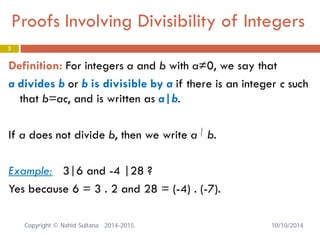

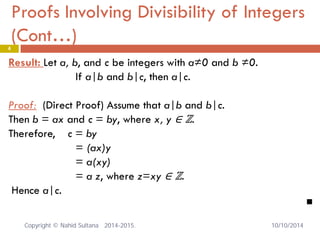

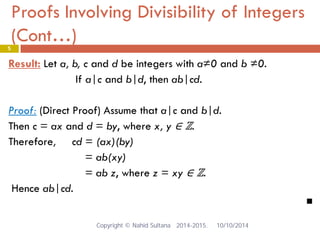

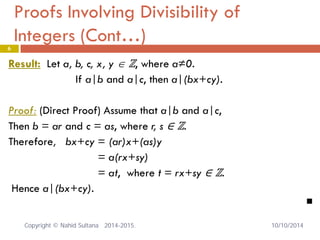

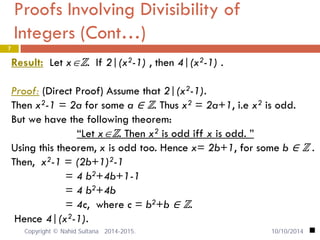

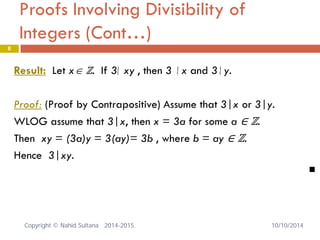

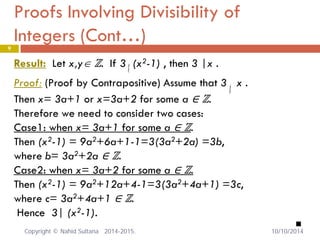

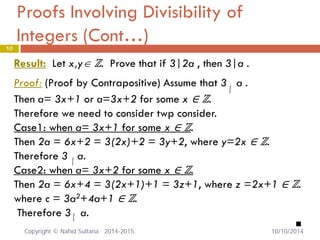

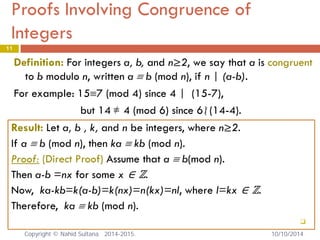

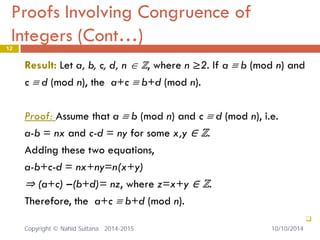

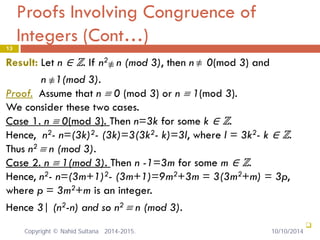

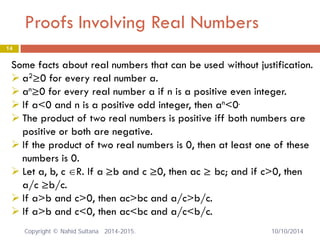

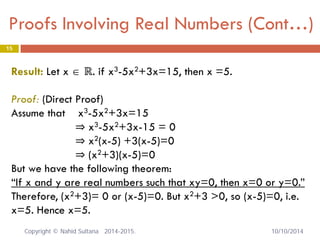

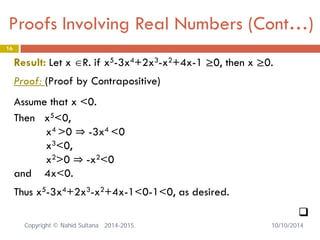

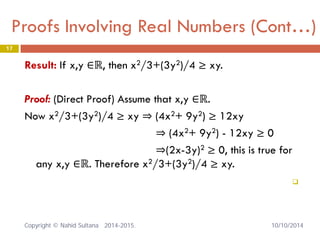

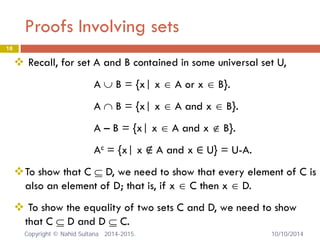

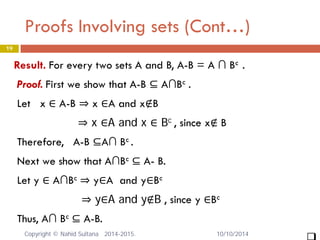

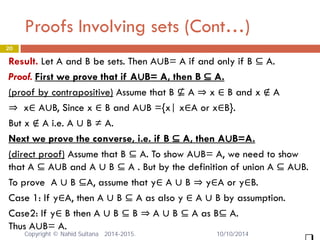

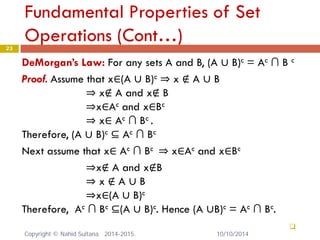

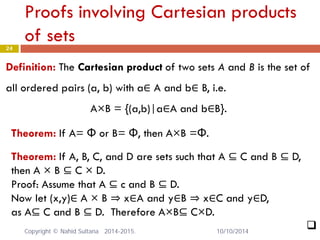

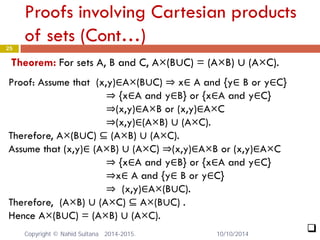

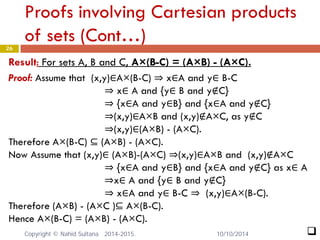

The document is a lecture on logic and proof techniques in mathematics, focusing on direct proof and proof by contrapositive. It covers proofs involving divisibility, congruence of integers, real numbers, and set operations, illustrating key results and properties. Various examples and theorems demonstrate the application of these techniques in mathematical reasoning.