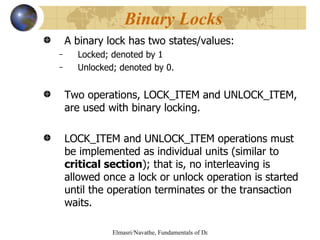

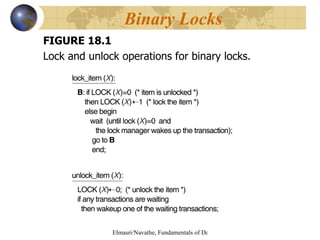

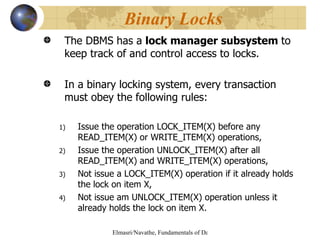

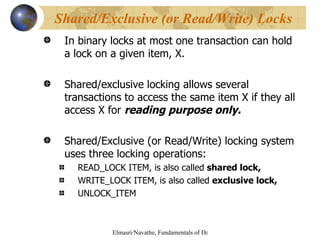

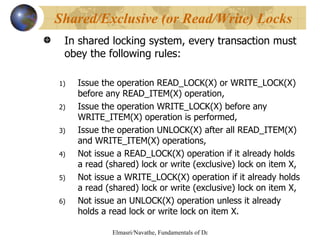

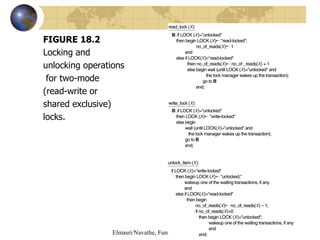

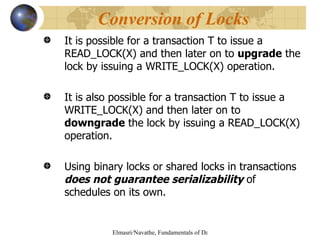

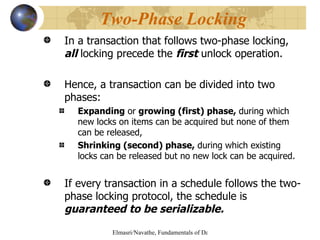

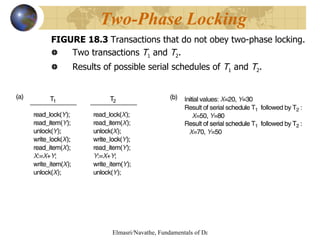

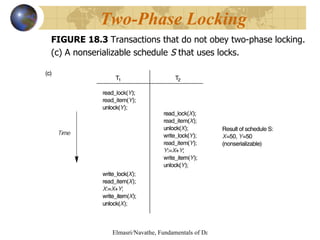

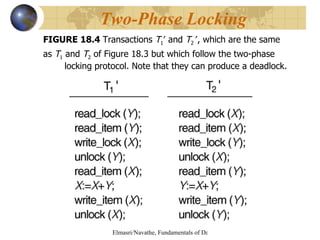

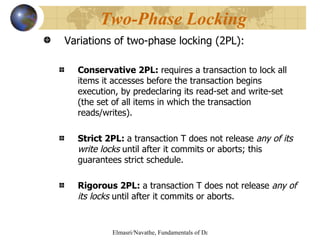

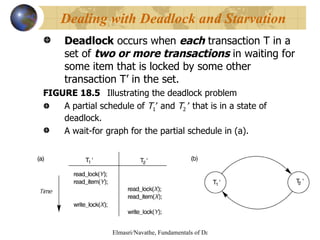

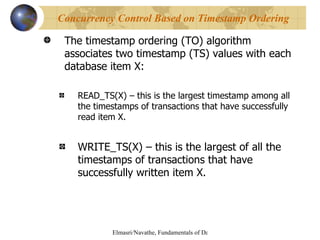

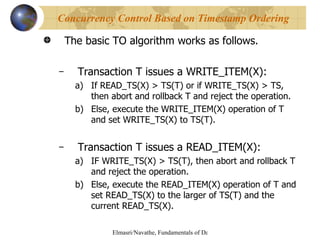

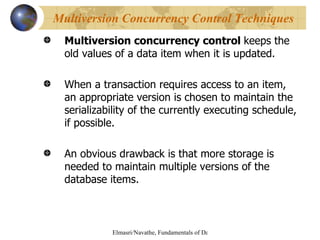

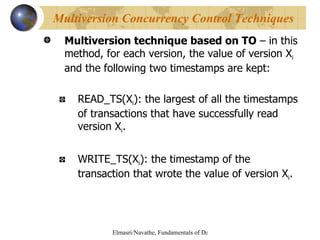

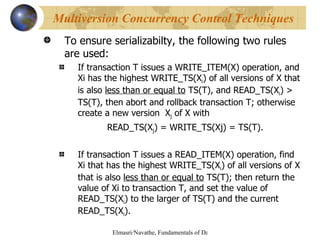

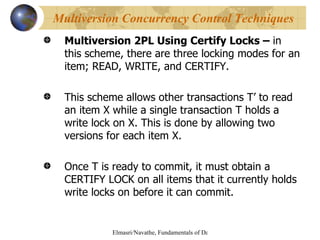

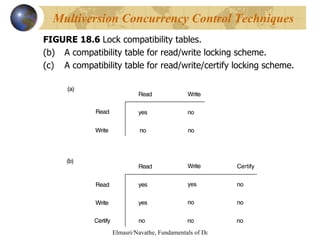

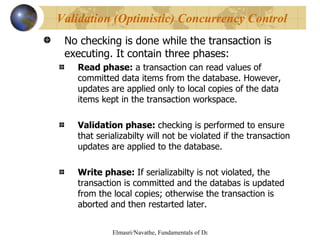

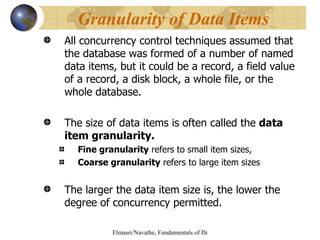

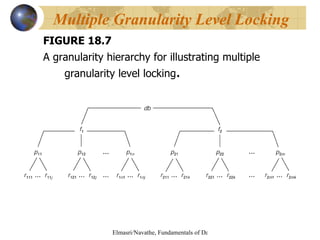

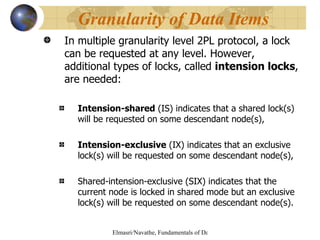

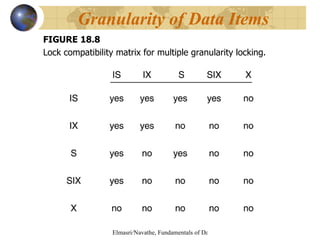

The document discusses various concurrency control techniques for databases including locking-based approaches like two-phase locking and multi-version concurrency control. It also covers non-locking approaches like timestamp ordering and validation (optimistic) concurrency control. Multiple granularity locking is described as a way to control concurrent access at different levels of data abstraction.