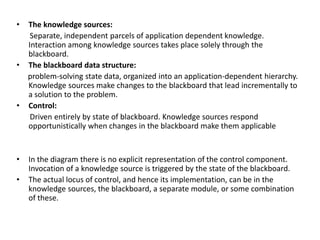

The document discusses several architectural styles for software systems, including pipe and filter, data abstraction/object-oriented organization, and event-based implicit invocation. Pipe and filter architectures treat components as independent filters connected by pipes. Data abstraction/object-oriented styles encapsulate data and operations in objects that interact through method calls. Event-based implicit invocation uses events to trigger the implicit invocation of registered component procedures. Each style has advantages like reusability and disadvantages like reduced control flow understanding.