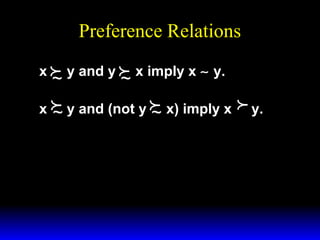

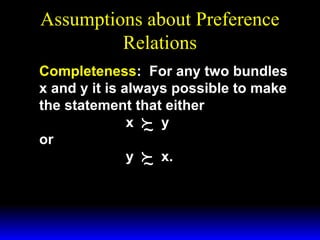

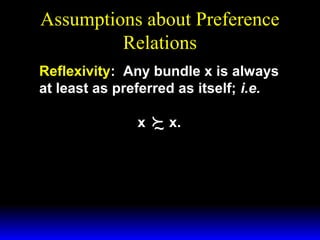

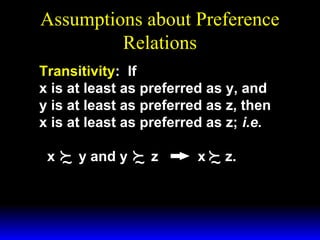

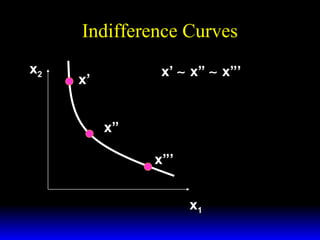

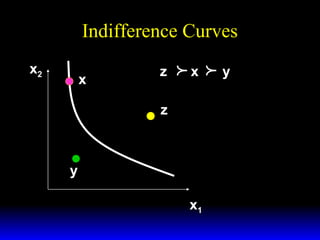

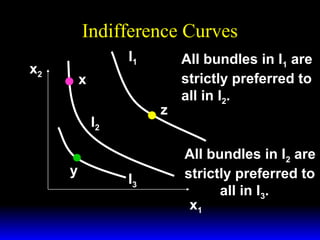

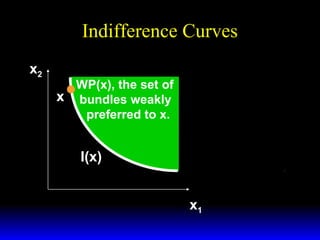

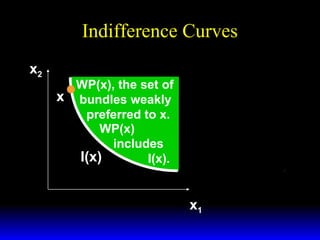

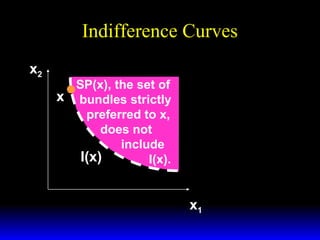

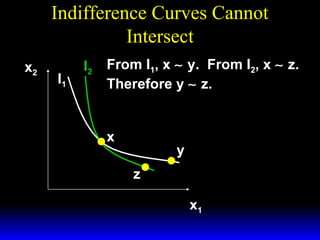

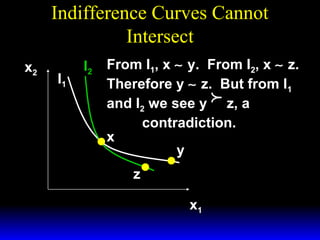

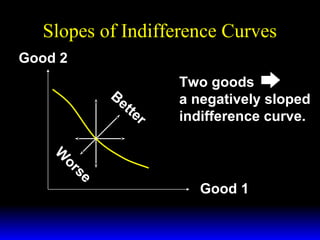

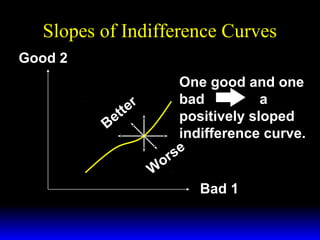

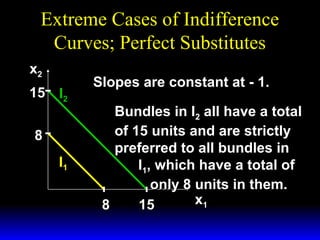

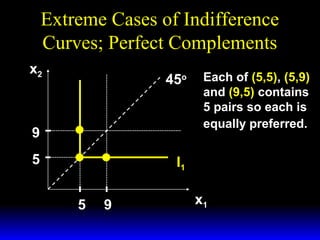

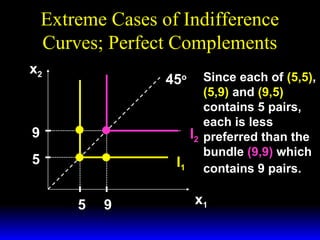

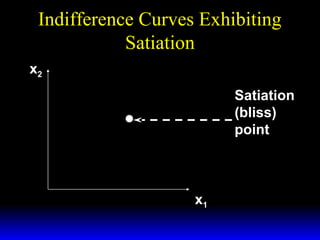

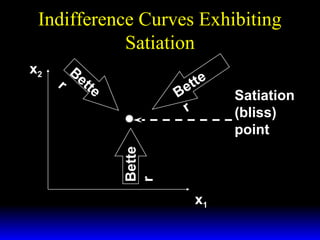

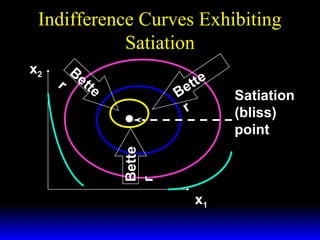

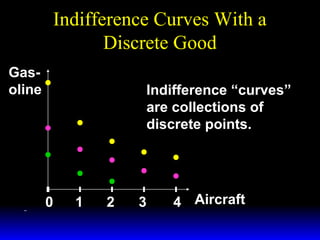

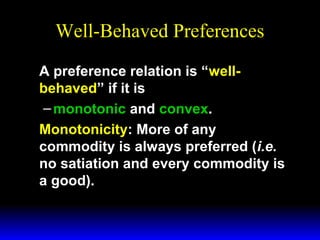

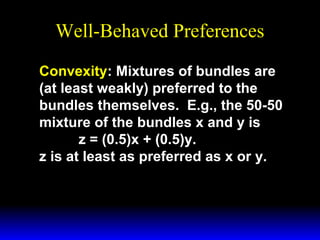

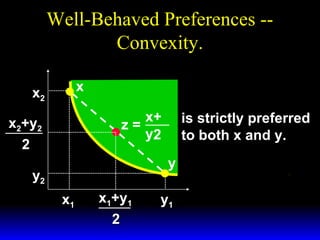

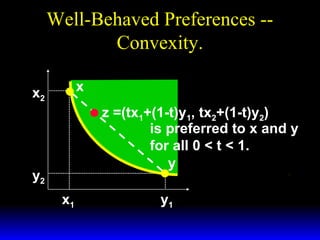

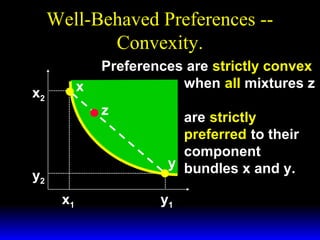

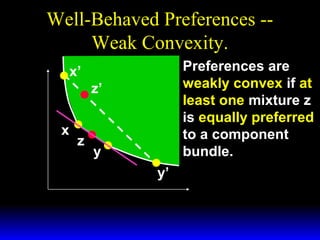

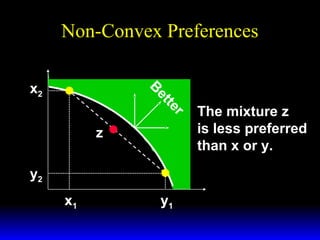

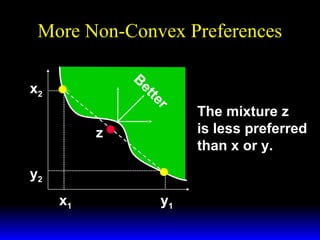

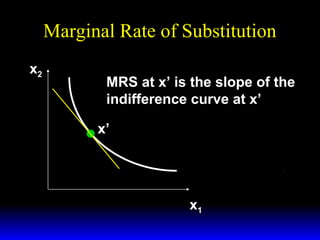

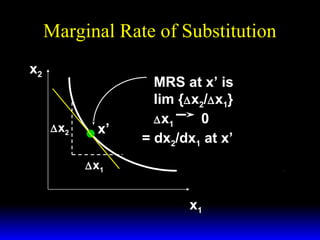

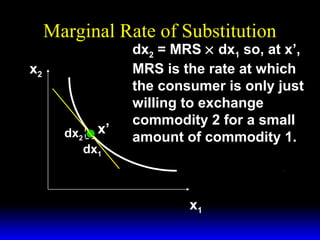

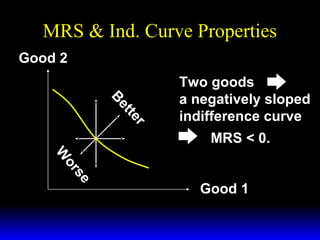

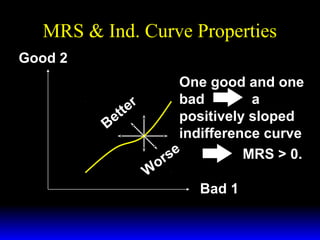

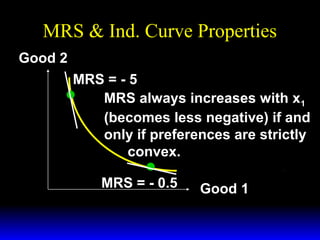

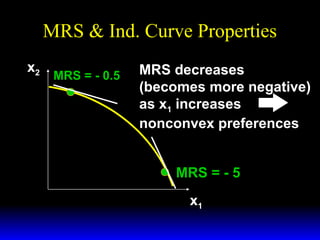

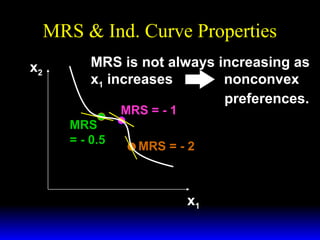

The document discusses modeling consumer preferences and indifference curves. It defines preference relations like strict preference, weak preference, and indifference. Indifference curves represent bundles that are equally preferred. They have specific properties like not intersecting and negatively or positively sloped depending on if goods are normal or inferior. The marginal rate of substitution is the slope of the indifference curve and represents the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another. Well-behaved preferences exhibit properties like monotonicity and convexity.