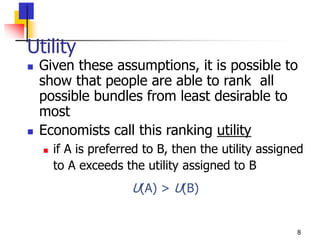

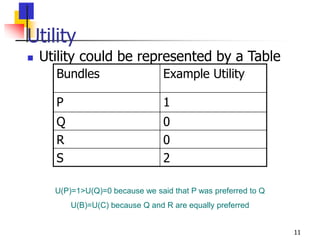

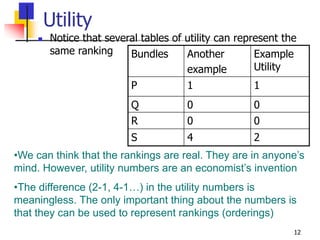

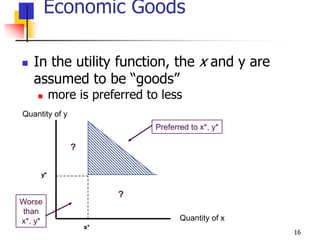

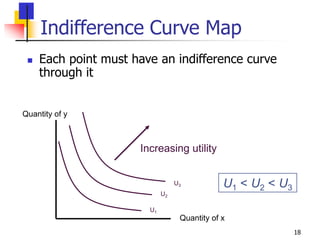

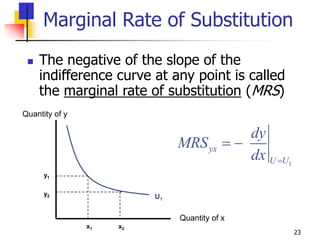

This document introduces the concept of utility and how it can be used to represent consumer preferences over bundles of goods. It discusses how utility rankings must satisfy certain axioms like completeness, transitivity, and continuity in order to be represented systematically. Utility is represented numerically using utility functions, with the rankings themselves being ordinal rather than cardinal. Indifference curves illustrate bundles that provide equal utility. The marginal rate of substitution measures how much of one good someone is willing to give up to obtain more of another good while maintaining the same utility. Utility functions take various forms, with Cobb-Douglas and perfect substitutes functions discussed as examples.

![30

Example of MRS

Suppose that the utility function is

y

x

utility

We can simplify the algebra by taking the logarithm of this

function (we have explained before that taking the logarithm

does not change the result because it preserves the ordering,

though it can make algebra easier)

U*(x,y) = ln[U(x,y)] = 0.5 ln x + 0.5 ln y](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cesproductionfunction-220923014234-d85dc7ce/85/CES-UTILITY-FUNCTION-ppt-30-320.jpg)