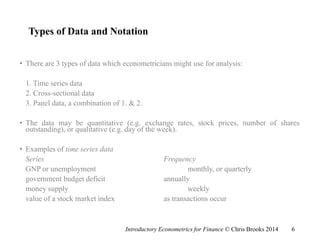

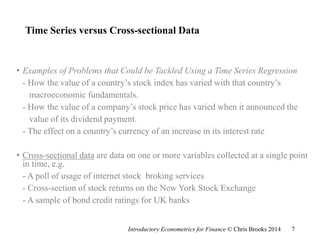

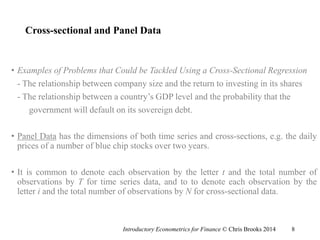

This document introduces the field of financial econometrics. It defines financial econometrics as the application of statistical and mathematical techniques to problems in finance. Examples of problems that can be solved include testing market efficiency, modeling volatility, and forecasting correlations. The document discusses different types of data used in econometrics, including time series data, cross-sectional data, and panel data. It also distinguishes between continuous and discrete data, as well as cardinal, ordinal, and nominal variables.