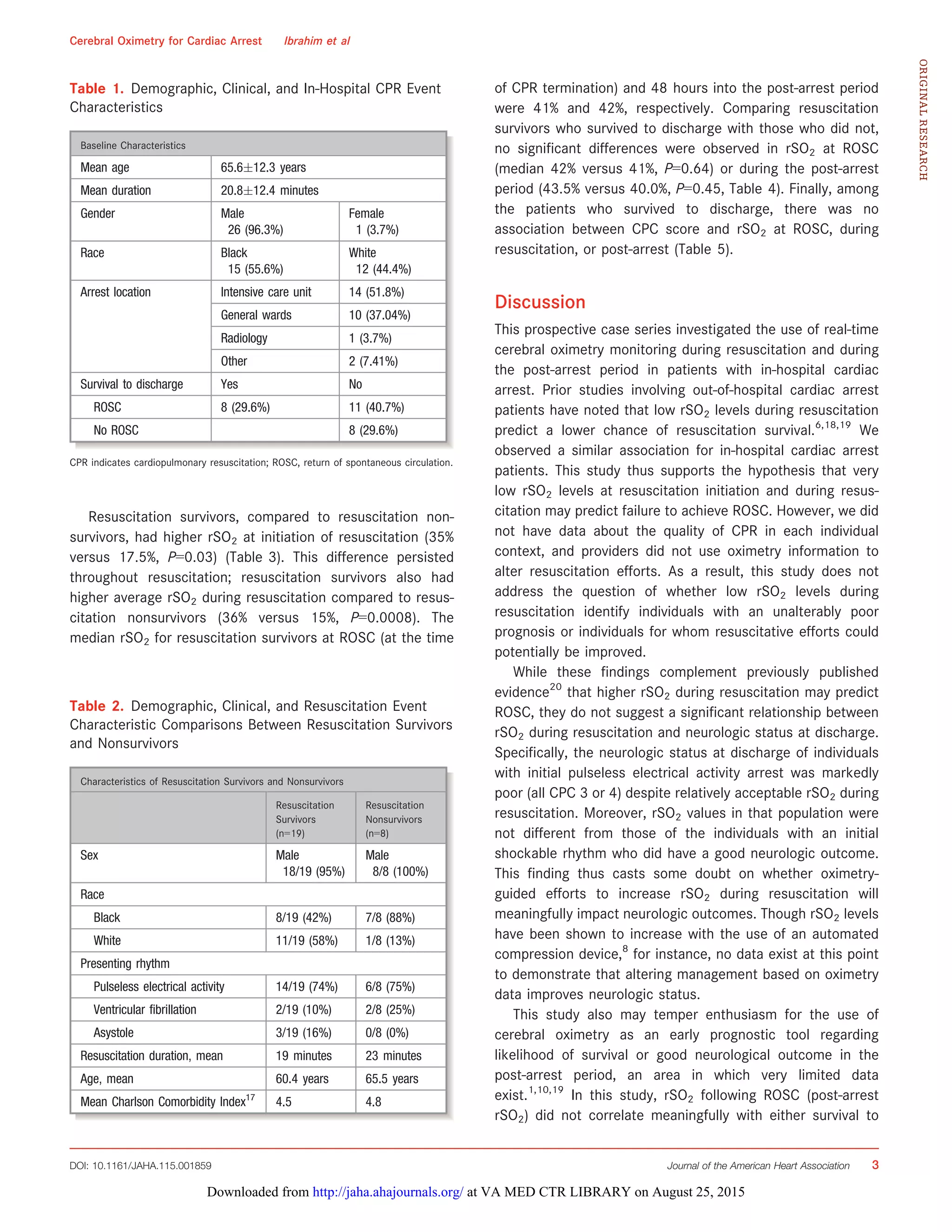

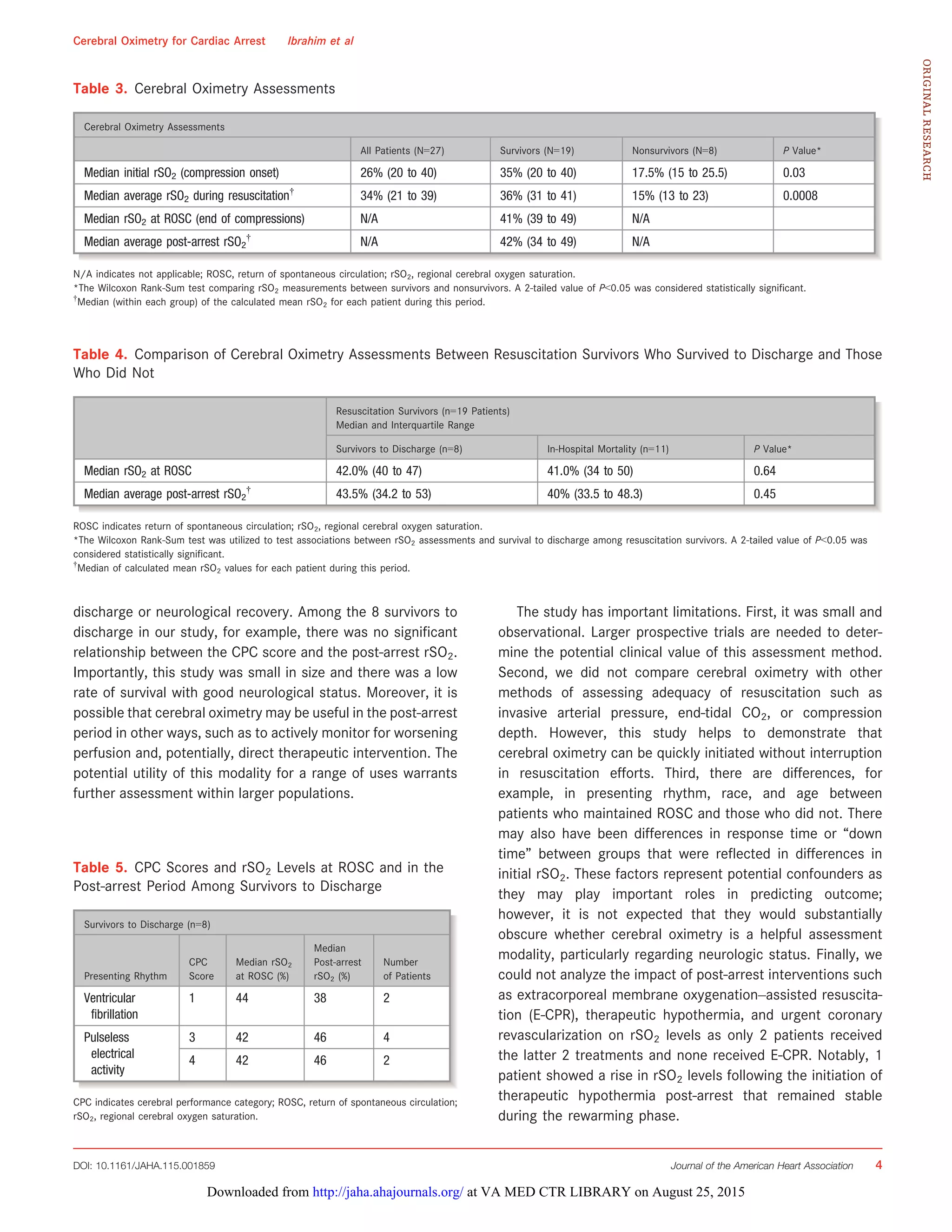

This study evaluated the use of near-infrared spectroscopy to monitor regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) during in-hospital cardiac resuscitation and post-cardiac arrest care. Higher rSO2 levels at the start of resuscitation and during resuscitation were associated with achieving return of spontaneous circulation, but rSO2 was not predictive of survival to discharge or good neurological outcomes. While rSO2 may reflect the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, larger studies are still needed to determine if rSO2 monitoring can be used to improve clinical outcomes after cardiac arrest.