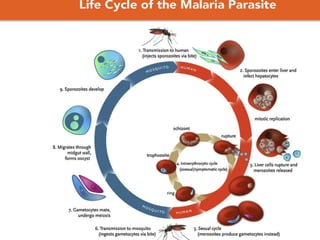

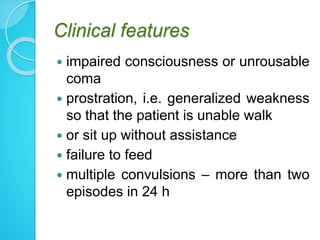

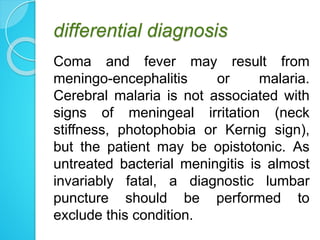

1. Cerebral malaria is a severe complication of malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum parasites sequestering in the brain. This can lead to coma and potentially death.

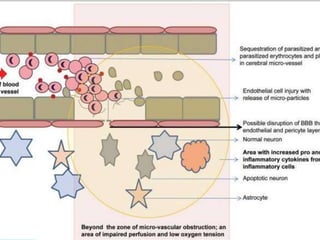

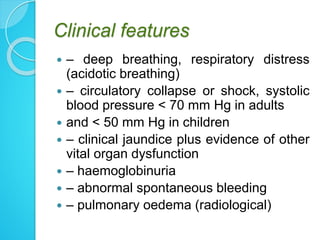

2. Parasites adhere to brain endothelial cells causing hypoxia, endothelial damage, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Cytokines also contribute to pathogenesis.

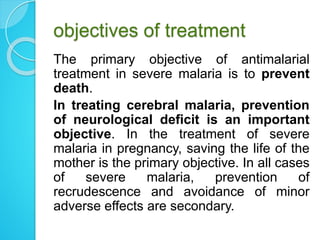

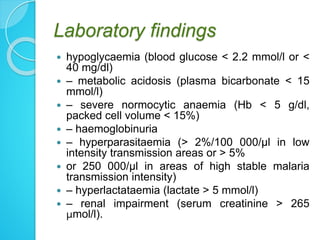

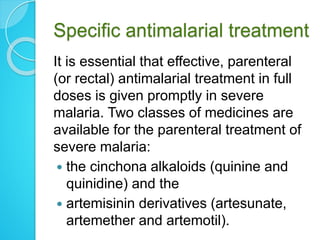

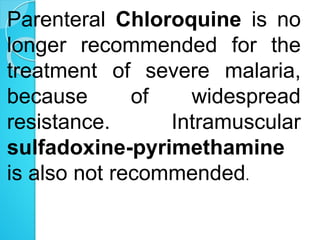

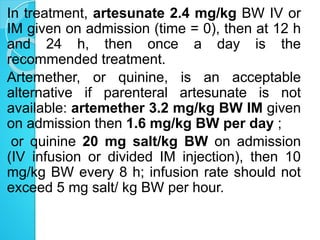

3. Treatment involves prompt parenteral antimalarial drugs like artesunate or quinine to prevent death. Managing complications and preventing neurological deficits are also important objectives.