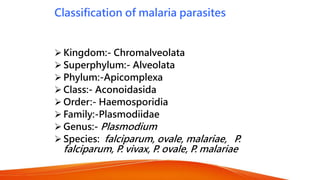

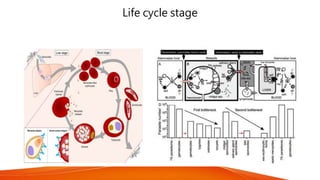

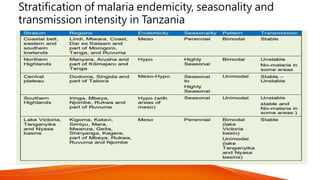

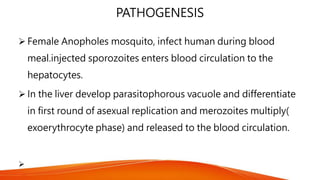

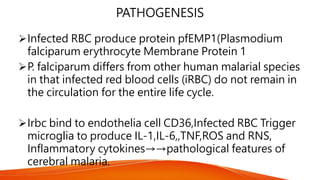

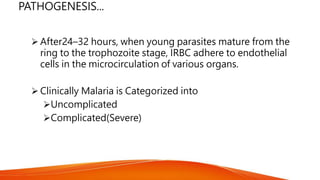

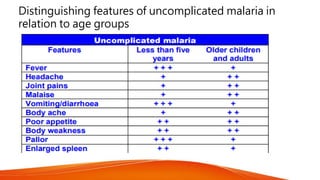

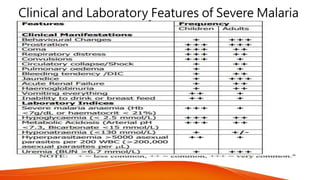

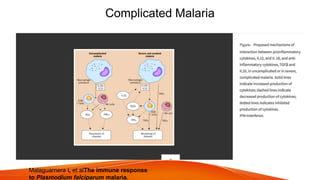

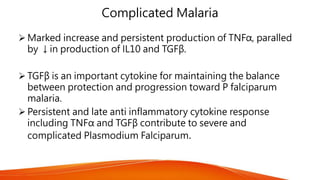

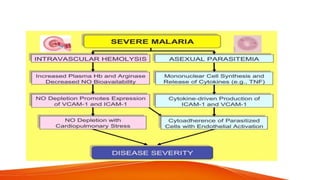

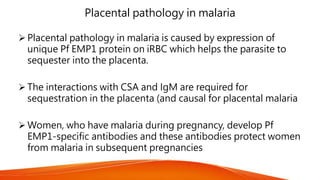

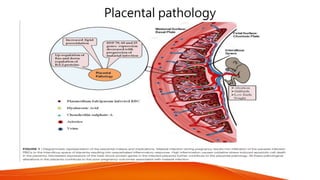

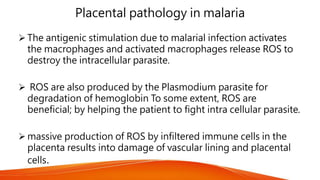

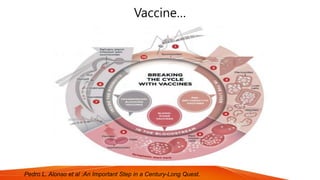

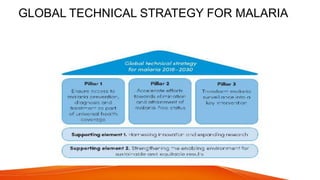

The document provides a comprehensive overview of malaria, detailing its classification, life cycle, epidemiology, and pathogenesis, particularly focusing on Plasmodium falciparum and its severe forms. It highlights the significant global burden of malaria, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, and discusses clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies along with recent vaccine developments. Key references and case studies emphasize the ongoing challenges and advances in malaria management.