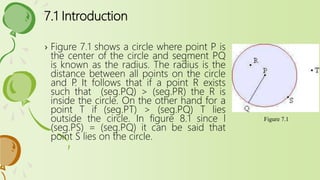

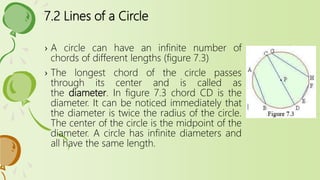

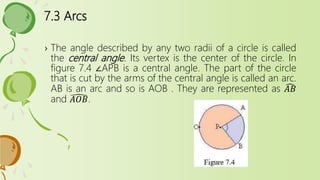

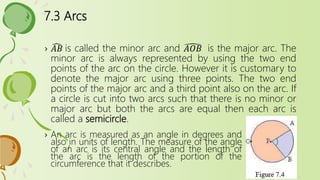

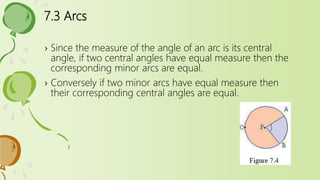

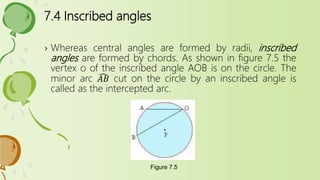

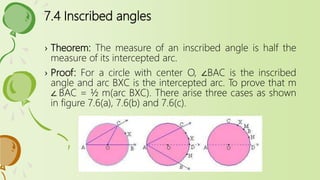

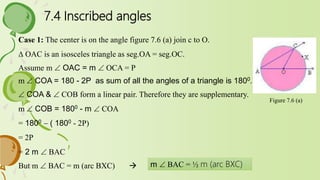

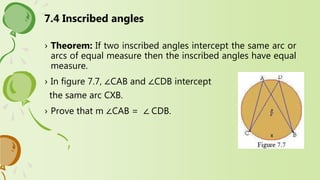

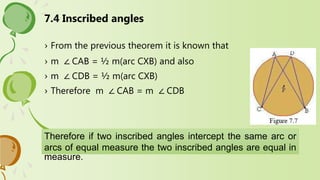

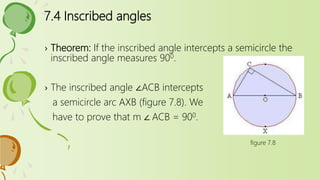

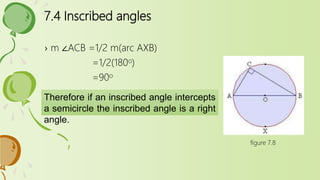

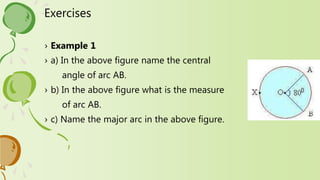

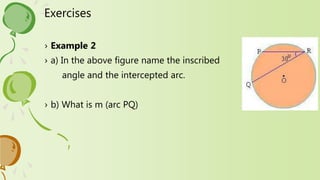

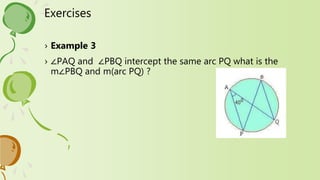

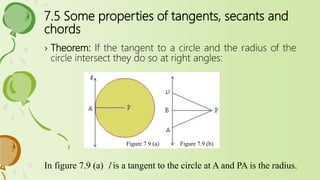

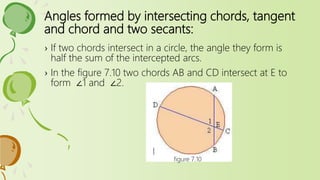

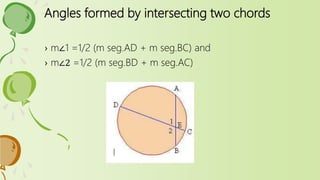

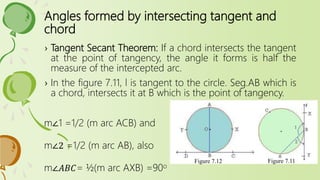

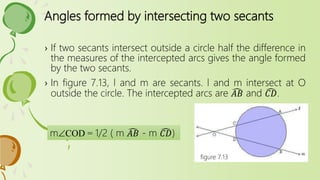

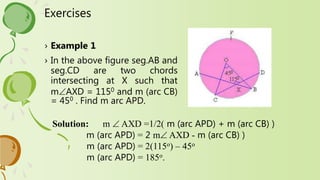

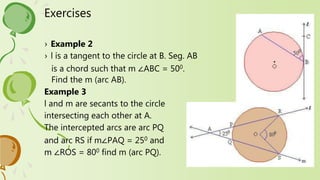

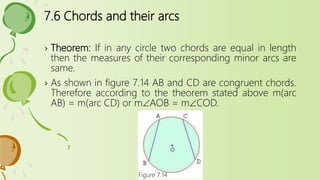

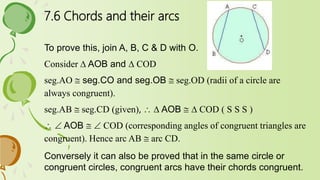

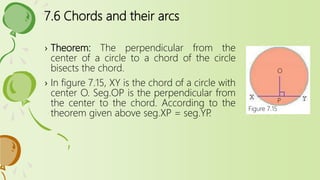

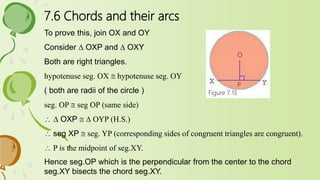

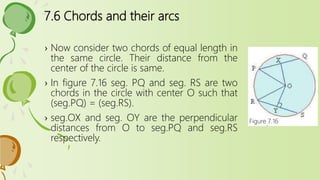

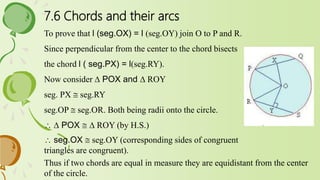

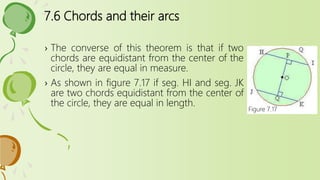

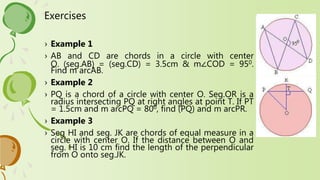

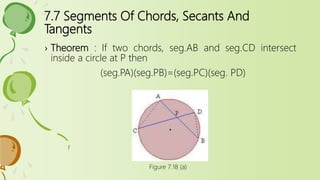

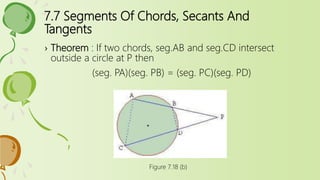

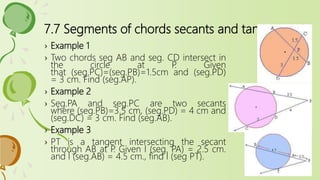

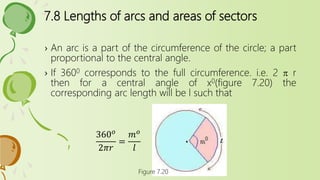

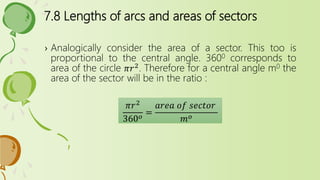

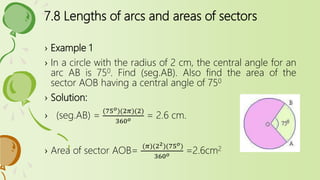

Chapter 7 focuses on circles, outlining their definitions, properties, and various related concepts such as lines, arcs, angles, chords, and tangents. Key topics include the classification of lines related to circles, the relationship between inscribed angles and arcs, properties of tangents and secants, as well as theorems related to chords and their measures. Exercises and examples throughout the chapter reinforce the foundational geometric principles associated with circles.