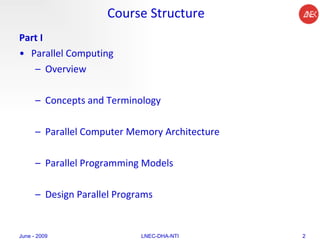

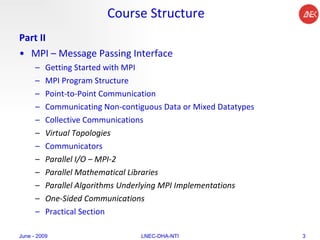

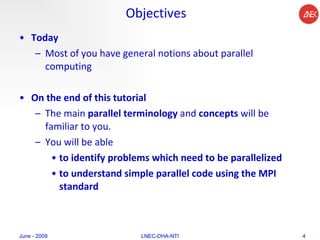

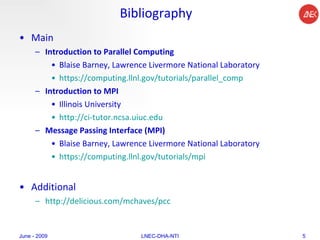

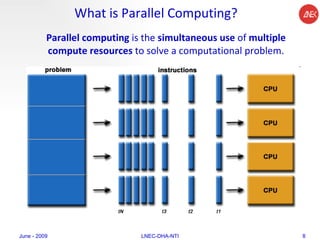

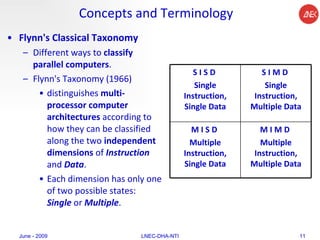

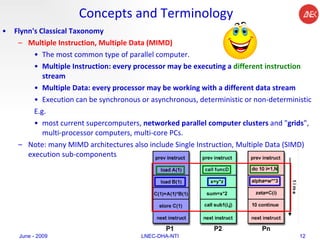

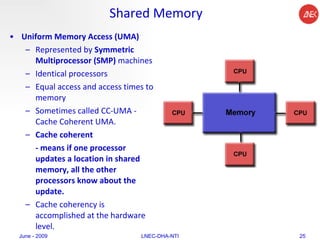

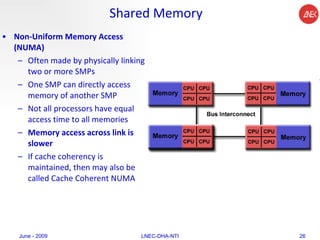

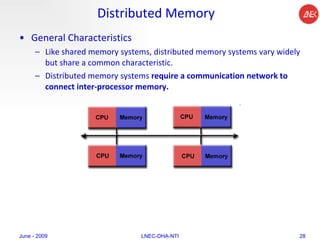

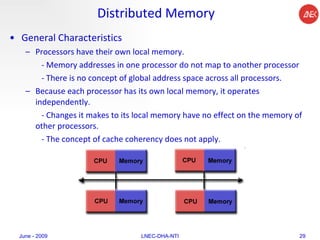

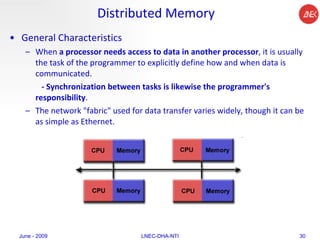

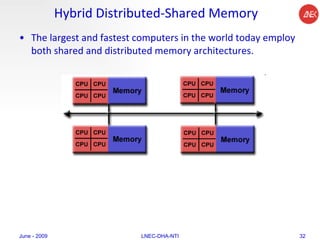

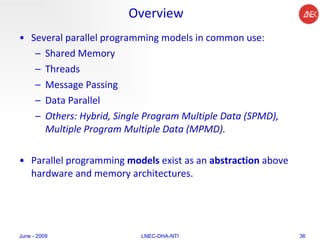

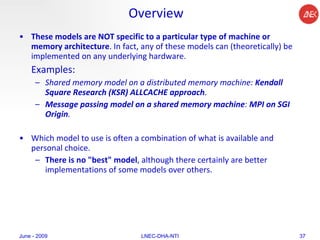

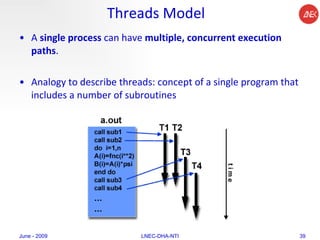

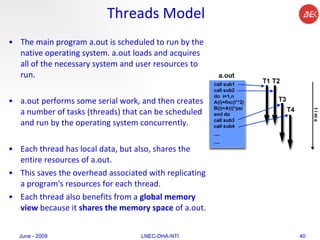

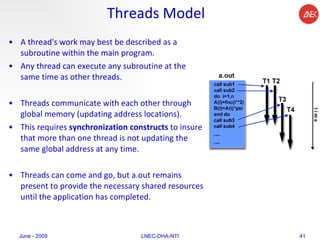

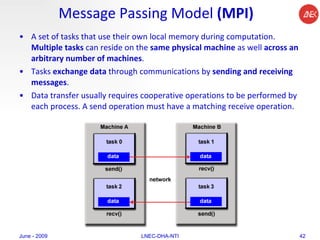

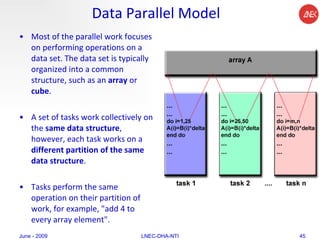

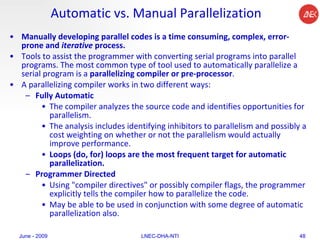

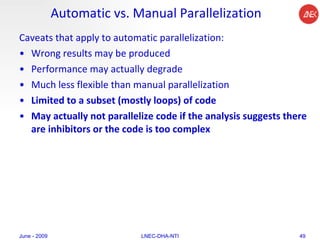

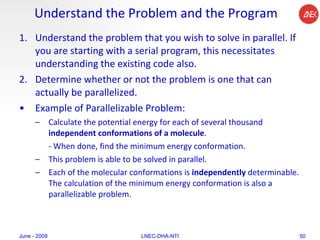

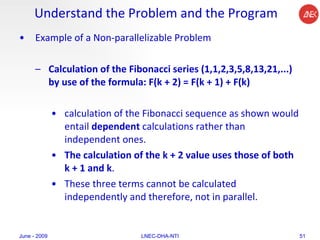

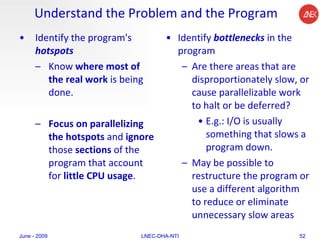

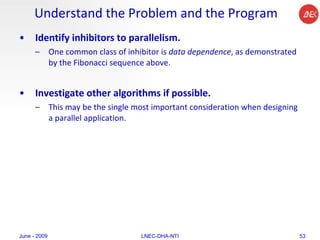

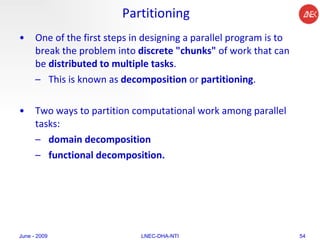

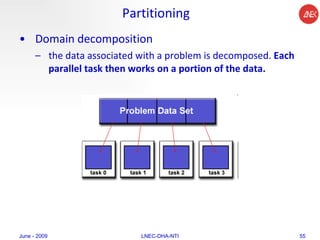

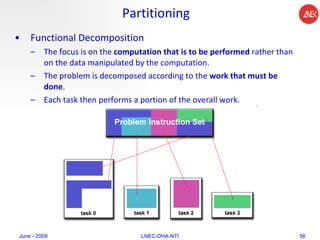

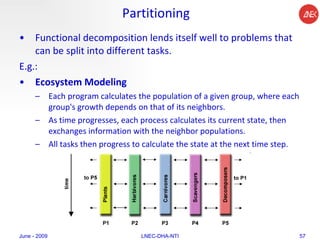

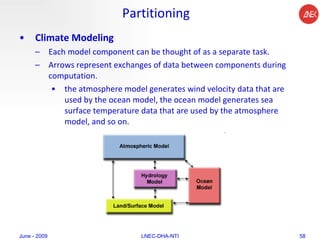

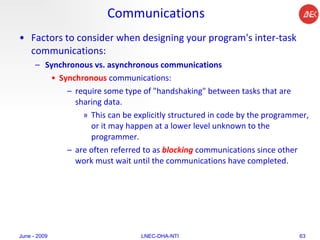

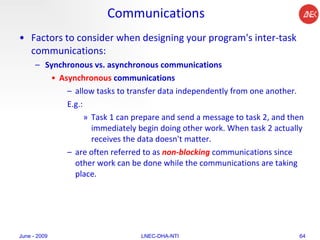

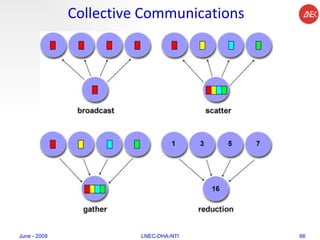

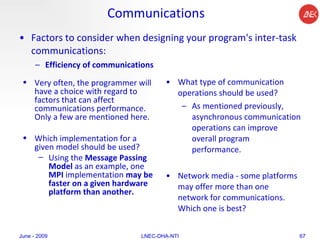

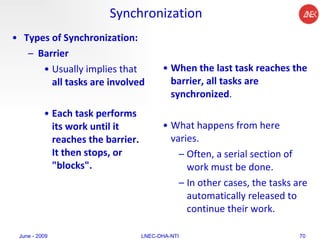

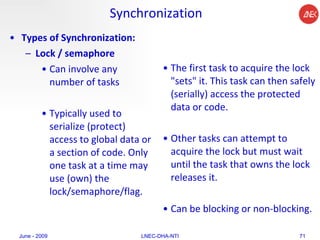

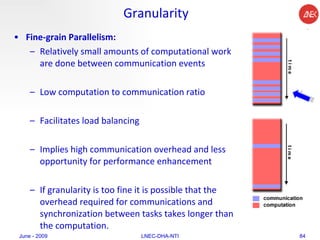

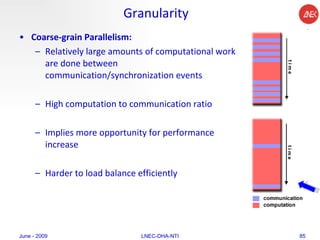

The document provides an overview of parallel computing concepts and programming models. It discusses parallel computing terminology like Flynn's taxonomy and parallel memory architectures like shared memory, distributed memory, and hybrid models. It also explains common parallel programming models including shared memory with threads, message passing with MPI, and data parallel models.

![Tutorial on Parallel Computing and Message Passing Model Marcirio Silveira Chaves [email_address]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c1pcmpishort-124612674397-phpapp02/85/Tutorial-on-Parallel-Computing-and-Message-Passing-Model-C1-1-320.jpg)