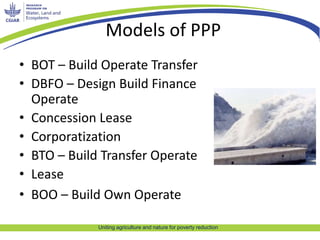

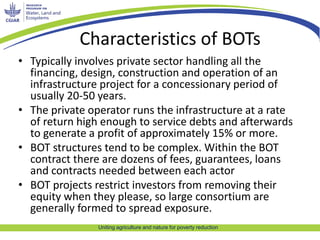

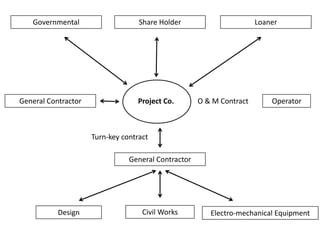

The document discusses Build Operate Transfer (BOT) and private sector-led hydropower development, highlighting the complexities, benefits, and challenges associated with these models. It outlines the historical context, expected growth of privatized infrastructure, and provides examples from the Mekong region, underscoring risks related to investor incentives and governmental capacity. The future focus is on enhancing monitoring, considering long-term impacts, and maintaining public control while leveraging private investments.