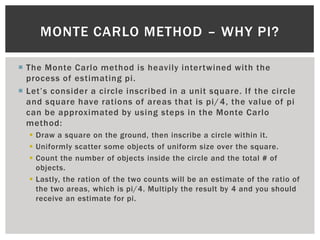

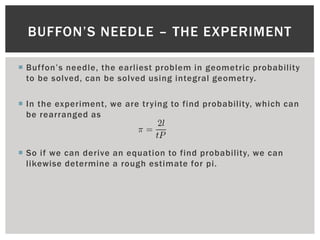

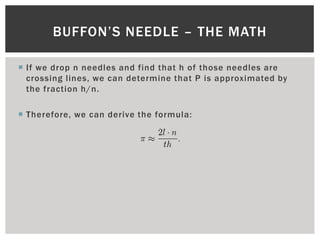

The Monte Carlo method involves generating random inputs from a probability distribution, performing deterministic computations on those inputs, and aggregating the results. An early example is Buffon's needle experiment, which aimed to estimate pi by dropping needles onto a floor divided into parallel strips. The probability a needle crosses a strip is related to pi, allowing pi to be estimated through repetition of the experiment. While accurate estimates of pi were obtained this way, the experiment is prone to manipulation by continuing trials until a desired precision is reached.