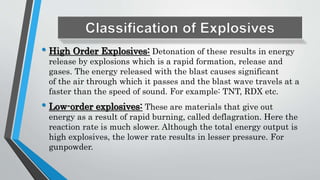

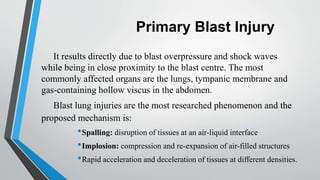

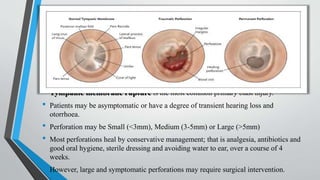

Blast injuries are physical trauma resulting from exposure to explosions. They are increasing worldwide from civilian and terrorist explosions. Blast injuries can be categorized as primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary injuries. Primary injuries directly result from blast overpressure and include injuries to lungs, ears, and hollow abdominal organs. Secondary injuries are caused by bomb fragments accelerating into the body. Tertiary injuries are from being thrown by the blast wind, and quaternary injuries include burns and psychological trauma. Management involves treating life-threatening injuries first according to ATLS protocol, thoroughly cleaning wounds, and using imaging tools like CT scans to aid diagnosis and guide further treatment.