This document provides an overview of the BASH shell and scripting in 3 sentences or less:

BASH is the Bourne Again Shell, the most common shell for Linux and UNIX systems. It allows running commands and writing scripts using features like variables, conditionals, loops, functions, I/O redirection, command substitution and more. The document covers the basics of BASH scripting syntax and examples of many common BASH scripting elements and constructs.

![CONDITIONS

• Same with the other languages, it does use IF ELIF and

ELSE

• The basic form of this is “if [ expression ] then

statement; else statement; fi” where expression is your

condition and statements are the block of codes that

must be executed upon meeting the condition

if [ expression ] then statement; else statement; fi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-26-320.jpg)

![CONDITIONS

#!/bin/bash

if [ “1” = “1” ]

then

echo “ONE”

fi

• Notice the space between the expression and the square

brackets, it is strictly required to have that

• This sample checks if 1 is really equal to 1, if true then

echo “ONE”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-27-320.jpg)

![CONDITIONS

#!/bin/bash

if [ “1” = “1” ]; then

echo “ONE”

fi

• This time notice the use of semicolon in which its

purpose is to separate statements and if you would

want it to be all in one line do this:

if [ “1” = “1” ]; then echo “ONE”; fi # See? ain’t it fabulous!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-28-320.jpg)

![CONDITIONS

#!/bin/bash

if [ “1” = “1” ]; then

echo “ONE”

else

echo “NONE”

fi

• Now with else part as what we expect will only be

executed only if the expression fails](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-29-320.jpg)

![CONDITIONS

#!/bin/bash

if [ “1” = “1” ]; then

echo “ONE”

elif [ “0” = “0” ]; then

echo “ZERO”

else

echo “NONE”

fi

• Now if you’re about to use multiple related conditions

you may use elif which is almost the same as if though

only comes after if](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-30-320.jpg)

![LOOPING

#!/bin/bash

COUNTER=0

while [ $COUNTER -lt 10 ]; do

let COUNTER+=1

done

• While loop iterates “while” the expression is true, like

the one we used to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-33-320.jpg)

![LOOPING

#!/bin/bash

COUNTER=10

until [ $COUNTER -lt 1 ]; do

let COUNTER-=1

done

• Until is a bit different as it will execute the loop while

the expression evaluates to false

• The example will loop until COUNTER is less than 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-34-320.jpg)

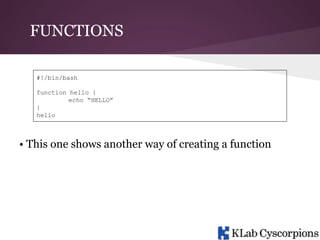

![FUNCTIONS

#!/bin/bash

is_hello() {

if [ “$1” = “HELLO” ]; then

return 0

else

return 1

fi

}

if is_hello “HELLO”; then

echo “HELLO”

fi

• In returning values, zero means true and the others

means false (false in the way you may use it)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-38-320.jpg)

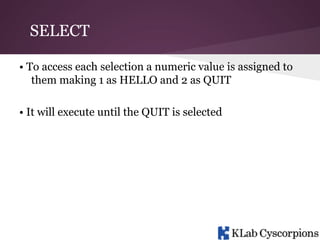

![SELECT

#!/bin/bash

OPTIONS=“HELLO QUIT”

select opt in $OPTIONS; do

if [ “$opt” = “QUIT” ]; then

exit

elif [ “$opt” = “HELLO” ]; then

echo “HELLO”

fi

done

• Select behaves like a for loop with a menu like selection

• This example will present a menu containing the

HELLO and QUIT as the options](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-41-320.jpg)

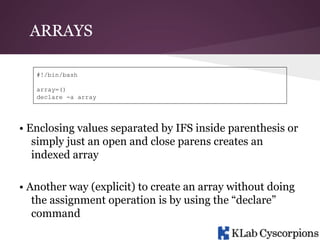

![ARRAYS

#!/bin/bash

array[0]=FOO

array[1]=BAR

array[3]=“BAZ BOO”

• Assigning values follows the format

“array_name[index]=value”

• Same as a regular variable, strings should be enclosed it

by quotations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-44-320.jpg)

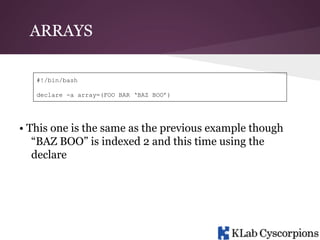

![ARRAYS

#!/bin/bash

echo ${array[@]} # Displays the elements of the array

echo ${array[*]} # Displays also the elements of the array but in one

whole word

echo ${#array[@]} # Displays the length of array

echo ${array[0]} # Access index zero also the same as ${array}

echo ${#array[3]} # Displays the char length of element under index 3

• Arrays like other languages are indexed from 0 to N,

where N is the total count of values - 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-46-320.jpg)

![ARRAYS

#!/bin/bash

declare -A array # Create a keyed array

array[FOO]=BAR

echo ${array[FOO]}

• This sample creates a keyed array using the “-A” option

of declare

• Assigning and accessing a value is the same as the

normal usage of array](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-47-320.jpg)

![ARRAYS

#!/bin/bash

BAR=(‘ONE’ ‘TWO’)

BAR=(“${BAR[@]}” “THREE” “FOUR”)

BAZ=(“${BAR[@]}”)

echo ${!BAR[@]}

array

# Create an array

# Add 2 new values

# Pass array

# Echo the keys of

• In order to get all of the keys of an array, use bang !

• Now in order to iterate a keyed array, use the variable $

{!BAR[@]} (like from the example) in the “in” part of a

for loop then make use of the values returned as the

index](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-48-320.jpg)

![INTEGER EXPANSION

echo $(( 1 + 1 )) # Echoes 2

echo $[ 1 + 1 ] # Echoes 2

SUM=$(( 1 + 1 ))

• Line 1 and 2 does the same thing, evaluate an

arithmetic expression same as the “command”

• Line 3 shows how to assign the result of the arithmetic

expression](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-53-320.jpg)

![MISC

SOME TEST OPERATORS:

-e

# is file exist

-f

# is regular file

-s

# is not zero size

-d

# is directory

-z

# is null or zero length

-n

# is not null

-h

# is symbolic link

SAMPLE:

if [ -d “/path/to/directory” ]; then

echo “HELUUU”

fi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bash-140226003122-phpapp02/85/Bash-60-320.jpg)