The document provides an extensive overview of asthma, detailing its pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy. Key learning objectives include understanding the inflammatory mechanisms of asthma, identifying treatment goals, and selecting appropriate therapies including beta-agonists and corticosteroids. It emphasizes the importance of individualized asthma action plans and the monitoring of treatment efficacy for managing both chronic and acute severe asthma.

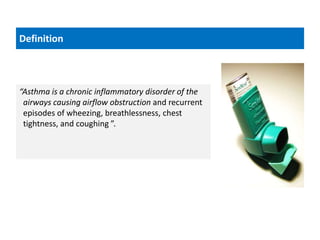

![• Plasma protein leakage induces a thickened, engorged, edematous airway

wall and narrowing of lumen with reduced mucus clearance.

• Late-phase inflammatory reaction occurs 6 to 9 hours after allergen

provocation and involves recruitment and activation of eosinophils,

T -lymphocytes, basophils, neutrophils, and macrophages.

• Eosinophils migrate to airways and release inflammatory mediators.

• T-lymphocyte activation leads to release of cytokines from type 2 T-helper

(TH2) cells that mediate allergic inflammation (interleukin [IL]-4, IL-5, and

IL 13).

• Conversely, type 1 T-helper (TH1) cells produce IL-2 and interferon-γ that

are essential for cellular defense mechanisms.

• Allergic asthmatic inflammation may result from imbalance between TH1

and TH2 cells.

Pathophysiology](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asthmamanagementmodified-200227130239/85/Asthma-Management-5-320.jpg)

![DIAGNOSIS

• Diagnosis is made primarily by history of recurrent episodes of coughing,

wheezing, chest tightness, or shortness of breath and confirmatory

spirometry.

• Patients may have family history of allergy or asthma or symptoms of

allergic rhinitis. History of exercise or cold air precipitating dyspnea or

increased symptoms during specific allergen seasons suggests asthma.

• Spirometry demonstrates obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second

[FEV1]/ forced vital capacity [FVC] <80%) with reversibility after inhaled β2-

agonist administration (at least 12% improvement in FEV1).

• If baseline spirometry is normal, challenge testing with exercise, histamine,

or methacholine can be used to elicit BHR.

CHRONIC ASTHMA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asthmamanagementmodified-200227130239/85/Asthma-Management-13-320.jpg)

![TREATMENT

• Goals of Treatment: Goals for chronic asthma management include:

✓ Reducing impairment:

(1)prevent chronic and troublesome symptoms (eg, coughing or

breathlessness in the daytime, at night, or after exertion).

(2) require infrequent use (≤2 days/wk) of inhaled short-acting β2-agonist for

quick relief of symptoms (not including prevention of exercise-induced

bronchospasm [EIB]),

(3) maintain (near-) normal pulmonary function

(4) maintain normal activity levels (including exercise and attendance at work

or school), and

(5) meet patients’ and families’ expectations and satisfaction with care.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asthmamanagementmodified-200227130239/85/Asthma-Management-16-320.jpg)