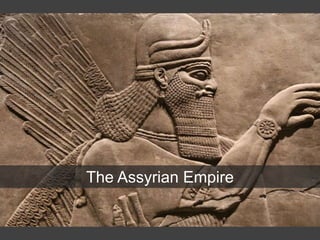

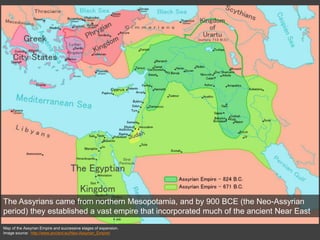

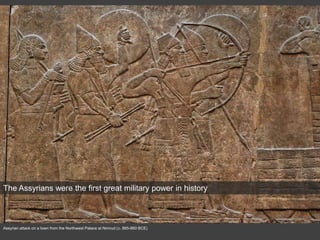

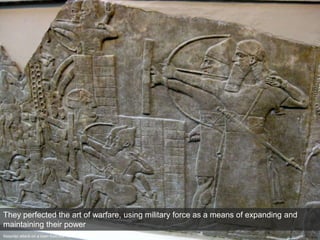

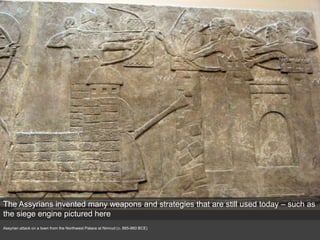

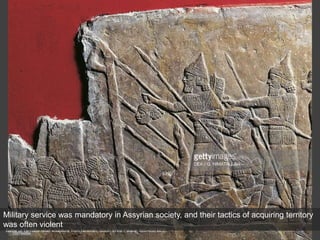

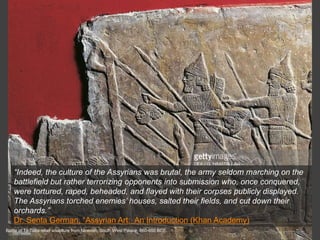

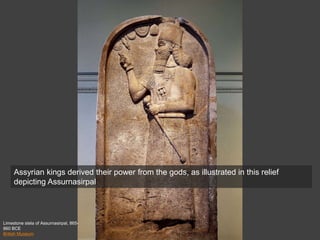

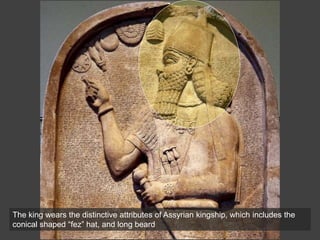

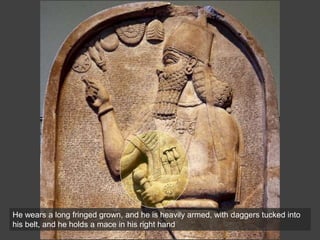

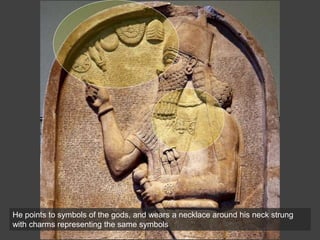

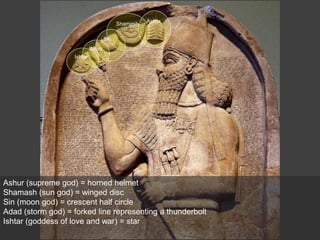

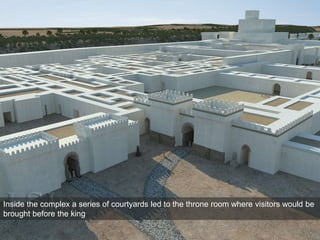

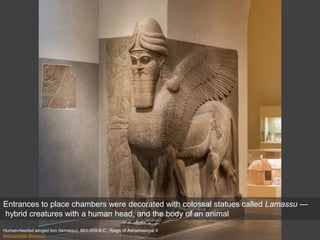

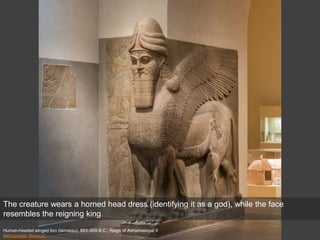

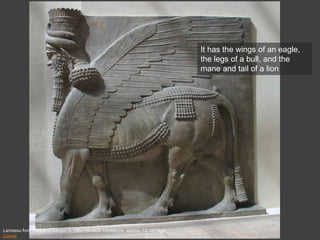

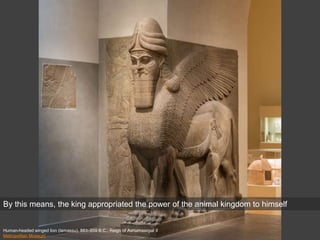

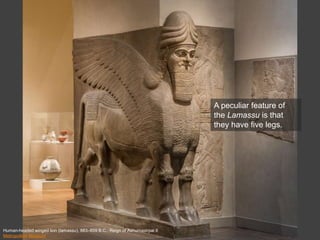

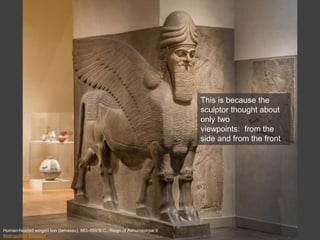

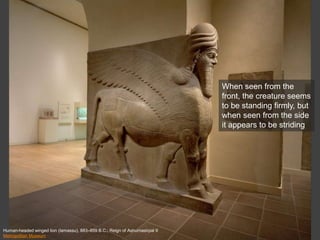

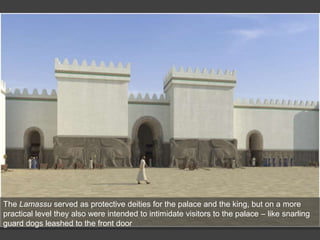

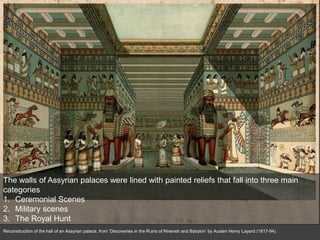

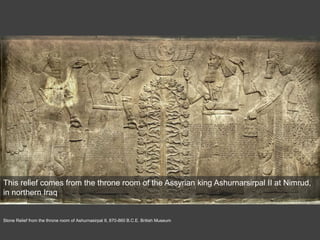

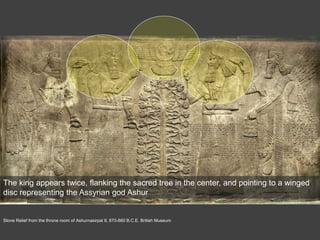

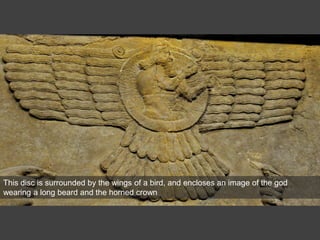

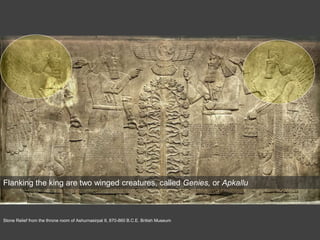

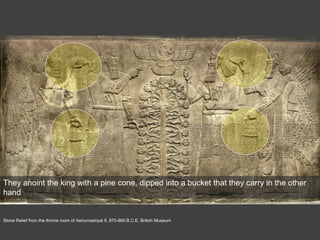

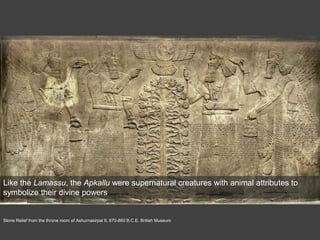

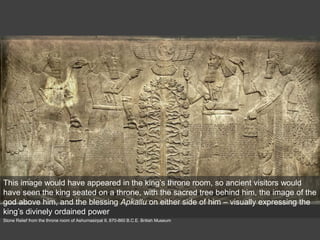

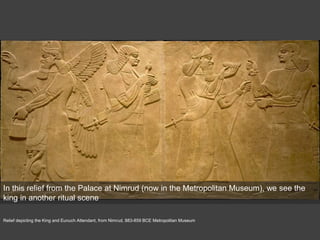

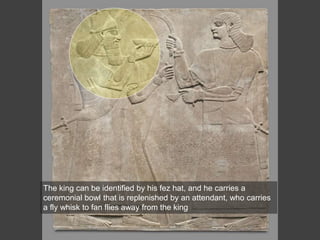

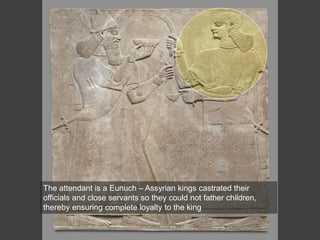

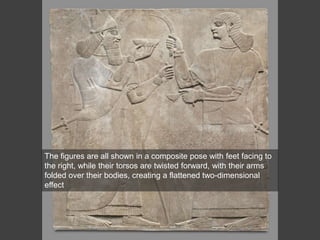

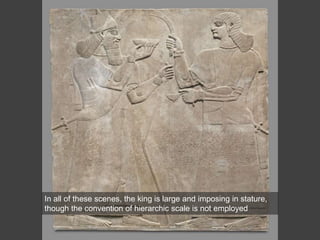

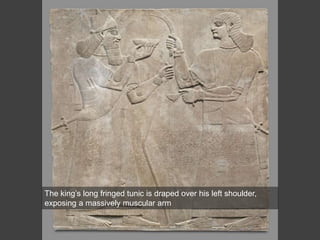

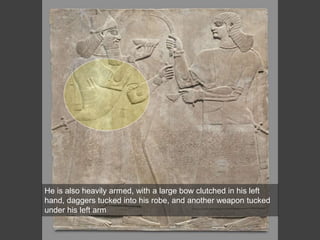

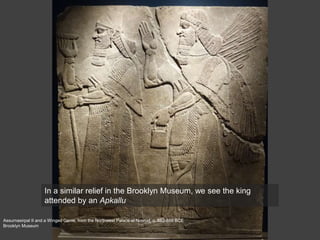

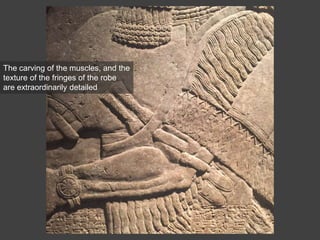

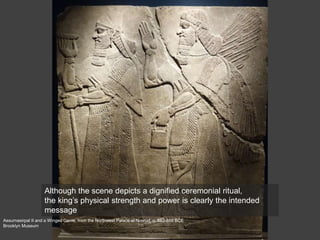

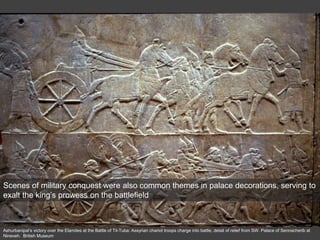

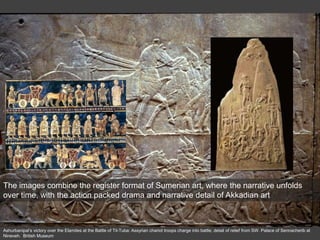

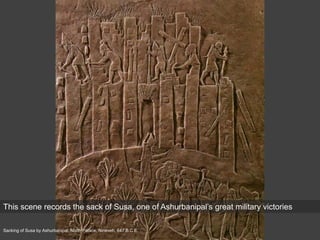

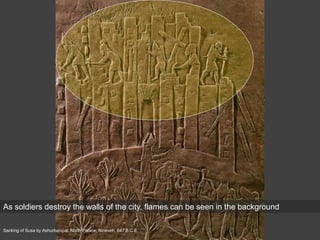

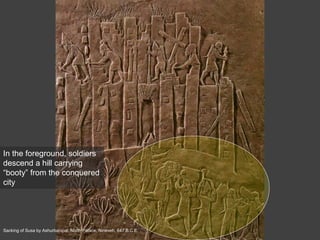

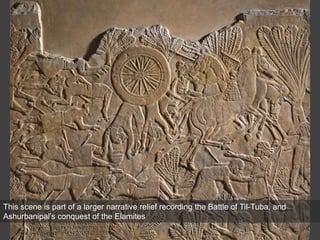

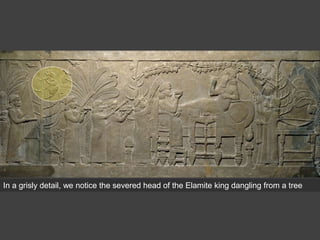

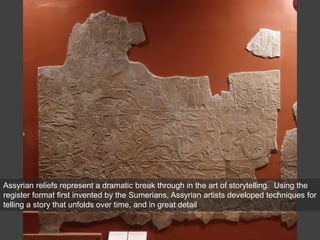

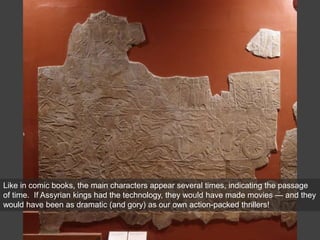

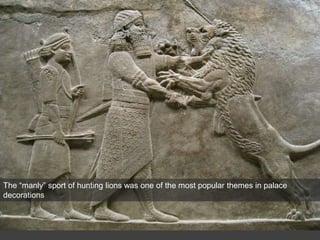

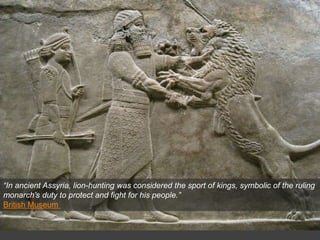

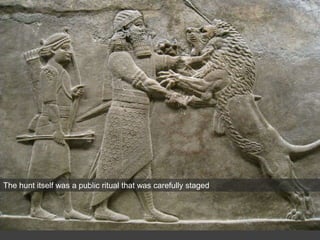

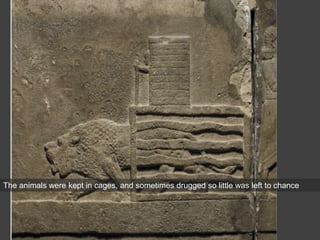

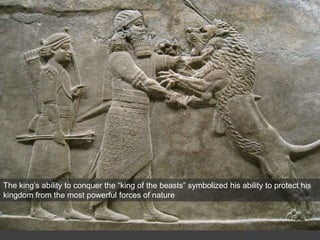

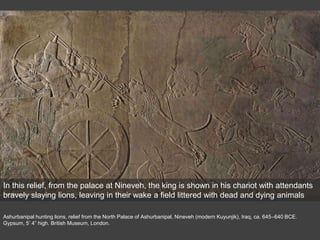

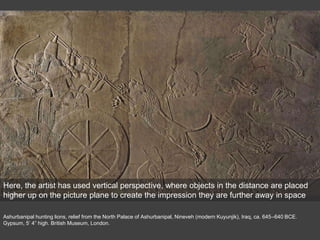

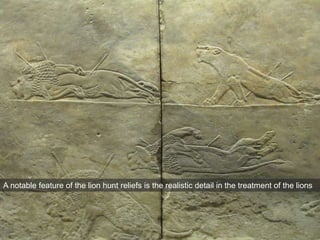

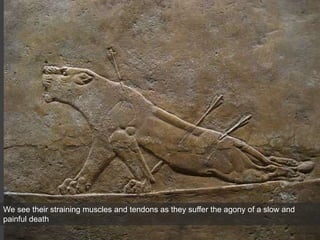

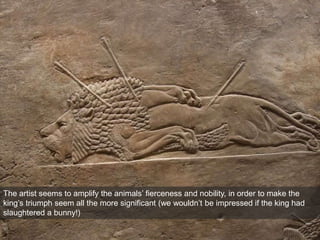

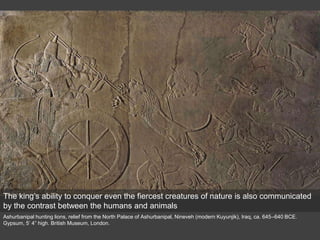

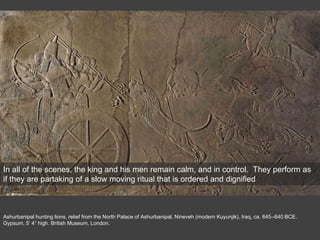

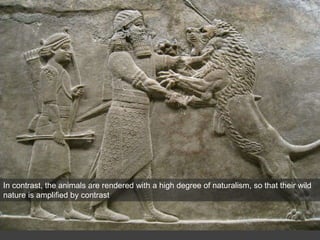

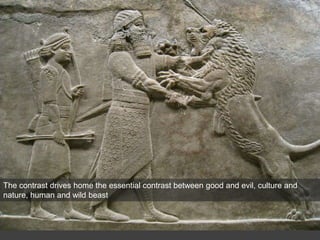

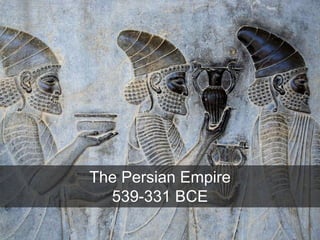

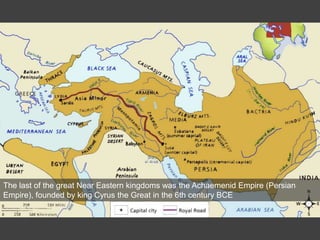

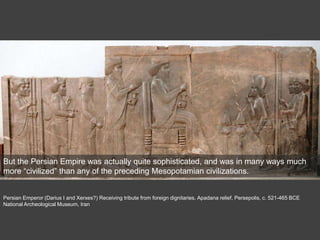

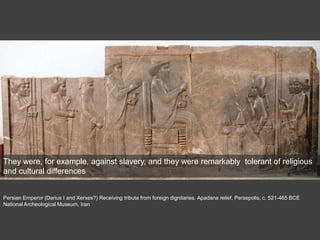

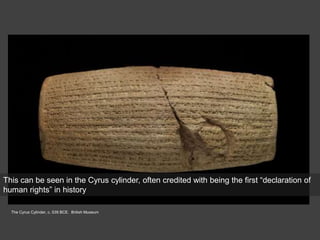

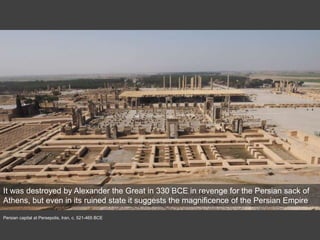

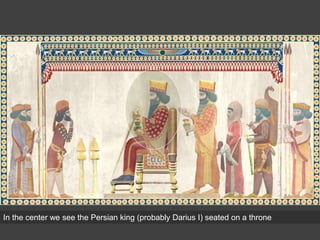

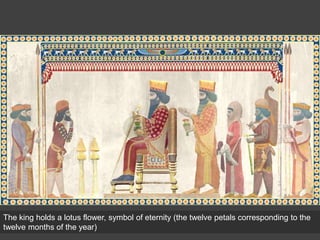

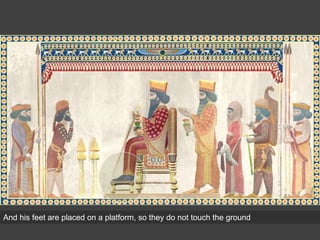

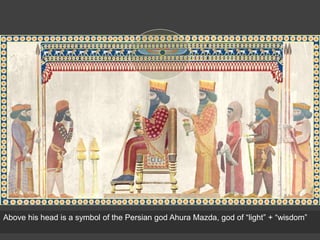

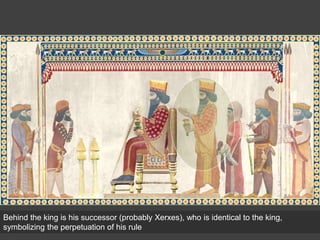

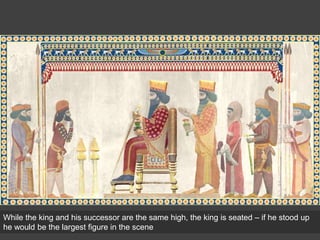

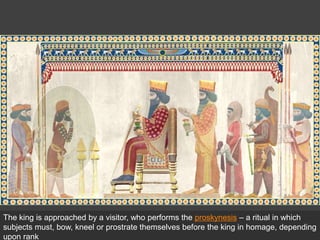

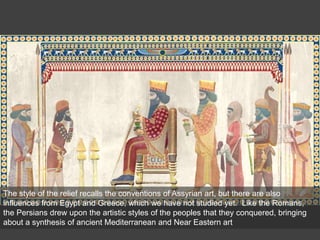

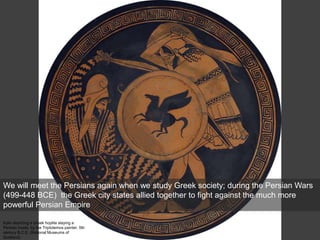

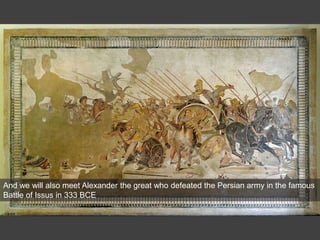

The Assyrian Empire originated in northern Mesopotamia and by 900 BCE had established a vast empire across the ancient Near East through effective military force. The Assyrians were the first major military power, inventing many weapons and strategies still used today. Military service was mandatory in their society. Assyrian kings derived divine power from gods and built grand palaces decorated with reliefs depicting ceremonies, conquests, and royal lion hunts to demonstrate their strength and rule. The last great Near Eastern kingdom before interaction with Greece and Rome was the Persian Empire founded by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE.